|

You are reading the older HTML site Positive Feedback ISSUE 42march/april 2009

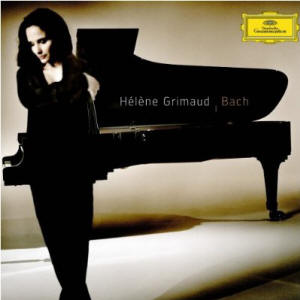

Hélène Grimaud's Hômage

to Bach: A Look Into the Mystical. A Review/Essay

Prelude Who am I to say anything about Johann Sebastian Bach, let alone engage in a discussion of Bach as a musical mystic? I have no credentials in musicology or theology. I'm just a guy whose opinions don't matter much in the scheme of things, despite my bravado posturing. Dare I presume, again, and wind up out of my depth? Oh, well. Here goes. This is my statement of humility before true greatness; Johann Sebastian Bach's and Hélène Grimaud's. My apologia. I hope you will go along with that and accept it as such. After all, "Writing about music is like dancing about architecture," in words attributed to Elvis Costello, Miles Davis, and Thelonious Monk, among others. Never was this more true than when writing about Bach. Attempting it turns me into the smallest and clumsiest of dancers. So pardon me for stumbling through my turn to dance. I know there are some of you who are more learnëd about music than I, and others about mysticism. So bear with me. It's just another of my half-baked opinions, but I hope you'll find it fun to read. If you are a newbie to Bach, I hope it whets your appetite for more. If you already have Bach as a daily part of your life, I hope it opens you up to Grimaud's approach. She plays Bach unlike anyone I've ever heard, and I've got lots of shelf space dedicated to his music. Trying to Express the Inexpressible There is something about Bach's music that brings to mind the word "ineffable," or "being unable to express in words." Can it be possible to express what listeners feel when they first hear a Bach fugue? It is, at best, an educated guess based on one's own limited experience. Consider the task of writing a fugue, or a two-part invention, or a three-part invention. The composer must write a piece that will follow the conventions of his era regarding melody, harmony, and counterpoint, all of which must be played from squiggles on lined paper by a later soloist at the keyboard of a pipe organ, a harpsichord, or a more modern piano. This performer must translate the notation, separate each of the parts, and keep them distinctly identifiable to the listener as the music gets increasingly dense. Listening to a well-written, well-performed piece of such music generates in me the reaction, "miraculous." One human mind has created this music, and written it down, so that another human mind, that of a musician far away, and two-and-a-half centuries later, can play it for us. This process exemplifies a defining characteristic of "civilization;" the writing down of what we think and feel, and music we play, for succeeding generations. We've devised a method of continuing our culture. For me, Grimaud's playing of Bach's music is something of a miracle, or "an extremely outstanding or unusual event," sometimes "manifesting divine intervention in human affairs." I'll omit the notion of Divine Intervention here, but I admit when I hear a Bach fugue, or multi-part invention, the notion of a "secular miracle" comes to my mind. Bach and Grimaud light up my brain like a pinball machine, an extraordinary event. This "rush" gives extreme cerebral pleasure to me and armies of Bach lovers around the world. Imagine a composer with such masterful keyboard technique who can pull that ace from up his sleeve and use it in religious music in praise of the Divinity, just as easily as Puccini could write arias expressing love of another, or in praise of love itself. In the words of Carly Simon (?), "Nobody does it better" than J.S. Bach when it comes to religious music. Or, in Grimaud's words, "...God owes a lot to Bach."

Church and Bach This ability, Bach's well-documented style in many religious services (over 250 Cantatas, numerous Choral Preludes, numerous Oratorios and Masses) might establish him as a musical mystic. He communicates to his audience the ineffable quality of the Divinity by inducing a feeling of awe or wonder, and this particular ability is what I mean when I write about Bach in this way. And it is in that sense that (I think) Hélène Grimaud speaks of Bach as a "mystic." I think she speaks of Bach, er, um, "adoringly" because she responds to him, even measures her spiritual progress as an individual by how well she plays his music. I infer from her words and her work (though she never states it outright), that she must view herself as a bit of a mystic, at times a vessel for Bach's music, and I think playing his music is, for her, akin to "channeling" back to Bach's soul. I might stretch Noam Chomsky's notion of the DNA-driven development of human speech—and to a lesser extent, Steve Pinker's notion of the DNA-driven development of a nearly universal human morality (ideas that are enjoying a vogue just now)—as owing to Darwin's Theory of Natural Selection; and suggest music-making as an important part of our DNA-driven "human nature." We are the only species that brings musicians together for no greater purpose than to play music intended to please our sensibilities. There are other species that sing alarms as warnings against predators, and sing "siren-songs" as invitations to mate, but these are restricted to but a few species-specific melodies. However, we may not be totally alone in one regard. It is said that whales sing out of isolation and loneliness, perhaps as pre-cursors to mating? (Imagine a whale singing the blues!) We humans have such songs, (Hank Williams' "I'm so lonesome I could cry,") as well as anthems of national pride, cantatas in praise of God, lullabies to help babies sleep, communal songs for special tasks (harvesting, quilting), love songs, songs about love-lost, songs to celebrate marriage, and some songs that serve as funeral dirges. Music is a part of our "human nature." We are the most musical of creatures on the planet. Here I must re-state the oft-made observation that a great deal of surviving human music was composed under the aegis of The Church. Much of what we think of as "pure music" has its roots in some kind of meditation on the "relationship of man to the The Divinity." And in this enterprise—seeking to define man's relationship to The Divinity through music—J.S. Bach was a major contributor. Bach used his music (weekly, during most of his life) to demonstrate man's relationship with the Divine as organist in the Kapelle of the Duke of Saxe-Weimar (1708-1717), and later as Kapellmeister (music-director) at the court of Anhalt-Cothen (1717-1723). Finally, he was appointed in 1723 to the cantorship at the church of St. Thomas, Leipzig, where he remained until his death in 1750. Bach spent about forty years composing religious music of one sort or another. The Secular Bach That's all fine and good if there is a Divinity: but, suppose there isn't a Divinity. Well, if we substitute the "collective Mind" as the object of Bach's worship, his music still works. If we, each a little speck of humanity, an ant before the aspect of eternity, can listen to Bach as his mind illuminates our minds; and if he generates a series of tones that gives us goose-flesh, and chills up and down our spinal columns; and if we experience in this a sense of "awe" and "wonder" that Bach can reach out to us from a distant time and place and give us this experience; then, I think, it's not too much of a stretch to say that Bach can be seen as celebrating the human condition, our collective Mind. If we find belief in a super-natural being too far to go to enjoy Bach's music, that's a way we can experience Bach in our increasingly scientific, materialistic, and secular culture. We can think of him as, even if he wasn't, an "agnostic," because in these post-modern, relativistic times, it has been said, "Each man his own historian." From which it follows, "Each man his own theologian." We're the grown-ups, and we can tinker with the rules a bit. So, we can think, in our time, and try to deal with J.S. Bach as a manipulator of the various musical trends in play in his time, in his attempt to lead his congregation to "gnosis." We can try to see if we can learn how he came to be recognized as a pillar of European classical music. Consider the agnostic. That word breaks down to the prefix "a" meaning "without;" and "gnosis" meaning "spiritual truth" that leads to enlightenment. In other words, an agnostic is a person who doesn't believe in an epiphanous divine enlightenment of the individual. But I understand how many folks feel an epiphanic "click" when certain aesthetic events occur, which they see as "divinely inspired." I have no doubt that Bach was a pious Christian in his time. I can imagine Bach playing his Pasacaglia and Fugue very slowly, in a dimly lit church, on a German winter's Sunday morning, and everyone present coming away with the certainty of having stood eye to eye with God: but, I can also see this generation's teenagers (on or off drugs), hearing some mysterious Rock music, and coming away with the same feeling of "awe" and "wonder." Watching my young children master the multiplication tables, and (too young for instruction) sing in harmony, filled me with "awe" and "wonder." I conclude "awe" and "wonder" are parts of our human nature that might be triggered by a beautiful sunset, or a violent summer storm, or a moon landing, or music. Still Leads to Awe and Wonder We also might imagine Bach as a supreme technician, without belief in individual divine enlightenment, who arranged musical events to generate this sense of "awe" and "wonder" before God of the Bible. But, sometimes he as easily wrote secular music like "The Coffee Cantata," or "The Peasant Cantata," which were happy, often witty pieces employing many of the same devices he used while writing deeply religious music. In other words, Bach knew how to use this or that chord progression, major or minor mode, orchestrated with a final brass choir or a final fugal figure that could drift mysteriously into silence. Bach could produce uplifting, mysterious, humorous, or dance music at will. And remembering this might be a helpful way to think of Bach, especially Grimaud's Bach. Though belief in God, Bach's and Grimaud's God, seems to make hearing her playing Bach a bit more spiritual–and in that sense a richer experience for the listener. As modern listeners, we have the luxury of interpreting Bach's work as a layered music, interlarded with astonishing technique that merely lights up the material brain; or, as a profoundly pious effort to bring us to spiritual "awe" and "wonder," that might finally lead us to Gnosis. If we believe in either the Divinity, or the collective Mind, (or both), Bach still gives us a sense of awe and wonder, because (I think) it is part of our human nature, or how we are "wired" to process musical sounds, through parts of the brain, which sometimes might be called either our "soul," or our "individual mind." And in the mechanistic way of how chalk squealing on a blackboard gives us goose-bumps, Bach, the practical man, might have figured out how to use the music at his command to give us goose-bumps in service of praising the Divinity (and in service of forwarding his career). Some Random Thoughts: On another tack, there are some purists in the Bach community who say "What Bach wrote for the violin, ought to be played on a violin. What he wrote for the harpsichord, ought to be played on a harpsichord." "Nonsense," reply guitar buffs. "Hogwash," say modern piano fans. The word on the street is that Bach's music is like Piet Mondrian's painting. Mondrian filled his canvases using white and primary colors in geometric arrangements (squares and rectangles). Mondrian, as the (probably apocryphal) stories go, would look at his paintings in mirrors to see if they still made sense to him when viewed from right-to-left as well as left-to-right; upside-down as well as right-side-up. The idea was, the organizational principles were so strong, it didn't matter how one viewed any Mondrian painting.

With Bach, it doesn't seem to matter if a piece is transposed from its origin as a violin piece–with minor modifications—to a guitar piece; from a harpsichord piece to a piano piece; and I've even run across a transcription from an organ piece, the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor, BWV 565, for, imagine this, a solo violin—with major modifications. [Hear Andrew Manze, JS Bach: Four Violin Sonatas; BBC MM89 playing his "reconstruction" in D Minor.] In her liner notes Grimaud says; "... the instrument you play him [Bach] on hardly matters—the message transcends the vehicle." So it is with little surprise that two pieces on Hélène Grimaud's piano album (titled simply, Bach) are reconstituted violin pieces from Violin Partitas #2 and #3. Nor should it come as a big surprise that Grimaud would choose to use transcriptions of Bach compositions by Busoni, Liszt, and Rachmaninov in this collection. For even if a given composition of Bach's is written for one instrument, it is usually so well crafted, so structurally sound, it can be played on almost any other instrument (right to left, or upside-down), in any century, with only minor adjustments. Grimaud says; "For me as for many other musicians and composers, Bach is the Bible ... with an infinity of interpretations, through which you can renew your relationship to music, to yourself, and to the world." Although Bach (1685-1750) was born in the 17th century, he lived mostly in the 18th century, his works can successfully be heard through the prisms of Liszt (1811-1886), who began his musical career as a romantic and finished as an impressionist and a Churchman; and Busoni (1866-1924), who was taken with Liszt's work as a young man, but later became more experimental, writing in a more modern style later attracting Bartok, Webern, and Messiaen; and Rachmaninov (1873-1943), who will largely be remembered as the last of the great romantics; Grimaud is showing us that Bach can be played on any instrument, and can be refracted through the lenses of at least one19th century and two 20th century pianist-composers. Again she comments; "I wanted to create a programme alternating between his [Bach's] pure incantation and his music as seen through the eyes of other composers." Grimaud is not the first to see and appreciate in Bach the elements of timelessness and inter-changeability of instruments. Andrès Segovia transcribed some Bach violin works and lute pieces for the guitar; Wendy Carlos transcribed some Bach organ pieces for the Moog synthesizer; and more recently, Cameron Carpenter transcribed a few organ works for an electronic synthesizer built on an organ manual to sound like a pipe organ (only cleaner). Were Bach alive today he'd likely own a synth like Carpenter's and he'd enjoy playing modern piano duets with many contemporary musicians who've demonstrated a reverence for his work, such as jazzmen Dave Brubeck, the MJQ's John Lewis, or Jacques Loussier. Bach had admirers in his time, and since Felix Mendelssohn championed a revival of Bach's music beginning in 1829, with a performance of the St. Matthew Passion, Bach's been considered among the "fathers of European classical music," a too modest rank, I think.

La Mystérieuse Mademoiselle Grimaud It's a mystery to me why a few critics have decided to put Grimaud forward as "mysterious." I see that she views Bach as a mysterious composer, one who initiates us to the mysteries (religious or agnostic) of music, and (to a certain or uncertain extent) that she views her progress as a spiritual human being as a function of how she increasingly understands and plays Bach's music. That's not too mysterious for me: merely workmanlike. That she is also a rescuer of wolves, and owns a wolf habitat, makes her a lot more mysterious, in a D.H. Lawrentian way. Lawrence once wrote a novella entitled The Fox where the dénouement came when his heroine touched (or was touched by) a wild fox, and she received so strong an energy charge it caused her to become unsettled. This literary description is not unlike Grimaud's telling of her first encounter with a wolf. All this would have intrigued the psychologist Wilhelm Reich. This thread of associations makes La Grimaud tres intéressant, and mysterious to me, although it has very little to do with her pianism. It makes her more interesting as a woman qua woman.

The Music Some critics, without seeking to know much more, note that Grimaud can show off her speed at the keyboard, and they seem to see it as nothing more than "look at me" attention-grabbing. Other critics hear her slowing down and lowering the volume as merely reaching for "contrast" from speed, even though she offers in the album notes; "The fugue is in effect one great crescendo, but as Glenn Gould showed us, withdrawing at the end of a crescendo is sometimes the most poignant climax." She doesn't merely seek contrast: rather, she is taking us somewhere deeply affecting, somewhere possibly painful, somewhere that stimulates "awe" and "wonder." She often accomplishes these affecting moments when we're not expecting it. To me this opens the notion that she is not a "me-too" Bach interpreter, a piano player who plays it safe. She is a risk-taker. I don't know what else to call someone who lives in daily contact with Bach and wolves. And I mean this as a compliment to someone who marches to her own inner drummer, who reads Bach in an intensely personal way (in this day of corporate aversion to risk taking). So, I'd say, listening to Grimaud we have to be acutely alert to, at the very least, changes of speed and loudness. The package sent me by D.G. includes a second disc available to the public for a few more bucks, and it is an option which I'd encourage you to take. It contains a DVD of Grimaud's playing the Busoni transcription of Bach's Chaconne in D minor, most of which she plays with her eyes closed. The rest is her interview that features Grimaud sitting on a sofa in her living room (I guess) and talking. It is a cool thing to have, because she is an attractive woman, with a light delivery and lots of charm. You might be tempted to take her as a lightweight because she is sooo charming and easy to look at. But when you've heard what she thinks about Bach's music, and you've read the interview in the album notes, you realize she's the real deal. I used to tend to take people with a Noo Yawk accent less seriously because they say "Chawk-lit" and I say "Chocolate." I stopped putting on my hi-hat about that decades ago. I learned not to confuse the accent with the substance. With Grimaud, it is a little harder to ignore her delivery because I agree with much of what she says. I've learned from her not to confuse charm with content. She doesn't need to sell herself. Ultimately, her playing speaks for her.

La Grimaud is also sensitive to Bach's accomplishments in other ways: for example, in her album notes (actually a partial transcription of the DVD interview), she speaks of "equal temperament" and so reminds us that Bach was among the first to embrace this system of musical intervals, moving away from perfect "natural scales" to the compromise filled "well tempered" scale. Perhaps, as Bach was also an instrumentalist, he was sensitive to the advantage of programming pieces in various keys without re-tuning. We can see how this system would be "keyboard instrument friendly;" and, perhaps Bach himself, who was a renowned harpsichord tuner as well as player, could see how this system was a time saver for keyboard instrument recitals. Bach was also a crackerjack organ repairman and tuner with a regional client list. Grimaud alludes to Bach's championing the well-tempered tuning system without going into detail, which makes it incumbent upon us to look this up in Grove's or Wikipedia. In particular, when asked why she chose a piece in C sharp minor, she replied; "I also wanted to move to a tonality which wasn't common before the advent of equal temperament. And the fugue—which is one of only two in five voices [my ital] in both cycles—is a tremendous piece which I've been working on ever since I was twelve." And Fugue Which leads us to the idea of multi-part fugues, and the incredible density of lines coexisting in the piece (Prelude & Fugue no.4 in C sharp minor, from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book1). It is amazing, and very dense music that lights me up. I have a theory. It is, Bach's more or less universal appeal is due to his ability to draw us in by playing a melody in slow or medium tempo; and then, with each contrapuntal variation he revs up the speed; until near the end, he has two parts, then three, and less regularly four or five lines all going along at more or less an AFAHP pace (that's As Fast As Humanly Possible); played in a way that we can follow without a brain-burn; and when he's got all this going, he'll do something like suddenly jumping from major to minor. And this one move, like the punch-line of a joke, is the unexpected something that, you suddenly realize, is the instant he's set us up for, just to give us this moment of brilliant clarity which we now recognize he's been planning since the beginning of the piece, (not unlike a Zen master who gives his student a problem to meditate on, only it is a problem without a solution, a Koan). When the piano student realizes that studying this piece of Bach's is analogous to the Zen exercise of trying to solve the insoluble problem, he "catches on" to—"that which happens along the way of a journey is more important than getting to its destination." In ways similar to what I've just described, but not the same as, I think I can understand how Grimaud relates to Bach, the mystic, and how each piece of music has something unexpected and enlightening for us, sometimes like a musical Zen koan that will help each of us along the path of our individual spiritual development; other times it might serve as a mere ornament, or it might evolve into an unexpected "joke." This may manifest itself in following the voices of a fugue; or keeping track of his various shifts of chromatics, or modes; or his doubling or quadrupling of the speed. I've heard Doc Watson and David Grisman playing around with many of the same elements. Bach does similar things in his music, but he aims higher. He aims at gnosis.

Summing Up Hélène Grimaud has offered us, in this album of some of Bach's greatest keyboard music, a fresh look at the mind of Johann Sebastian Bach, the inventor of European classical music. [I feel Bach's stature deserves some such sobriquet, as Louis Armstrong is often called by those who know, such as Wynton Marsalis, "the inventor of Jazz," and Bill Monroe was often called, "the father of Bluegrass.] If we view Grimaud's interview on the accompanying DVD, and read the transcription of it more than the obligatory fewest possible times, we're apt to find interesting Grimaud's opinions about Bach: "He was a mystic ... He was also a mad-man—he was literally possessed." These are the kind of things no one would've dared say about Bach before this era, making of him more a William Blake than like the many buttoned down, academically trained, composers of today. If we listen hard to her playing we will find some of the most "outspoken" performances of Bach currently available. This kind of approach to Bach is a breath of fresh air, in our corporate era. And I must say, I'm pleasantly surprised that Deutsche Grammophon would be the corporation to champion Grimaud. In conclusion: I find this album a "must-have" CD of some of Bach's most remarkable music. The playing is extraordinarily fine. The audio engineering is equally fine. The insight we get is the opposite of how Bach is most-often played; fiery and affecting as opposed to calm and cerebral. This is a recording, I think, that will raise Grimaud's stature over the years until she stands with Glenn Gould on piano, Pablo Cassals on cello, Marcel Dupré on organ, etc. I honestly feel this one will become a benchmark, a set of performances by which subsequent performances will be measured. While you're sitting at your computer, right now, punch in your favorite vendor and order your copy of Grimaud, Hélène: Bach (Deutsche Grammophon; CD 00289 477 7978) for the Standard Edition, or (CD 00289 477 6248) for the Limited Deluxe Edition. Do it now! In your mind, repeat after me: I can't live without this CD. I CAN'T LIVE WITHOUT THIS CD. And if you phone up instead, remember to tell ‘em Max Dudious said; "Grimaud really can't walk on water, but she's an ear-opening Bach interpreter." Ciao, Bambini. March 5, 2009

|