You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE

may/june 2008

Dan

Fogelberg's "Leader of the Band" - a Father's Day Homage

by Mike

Rodman

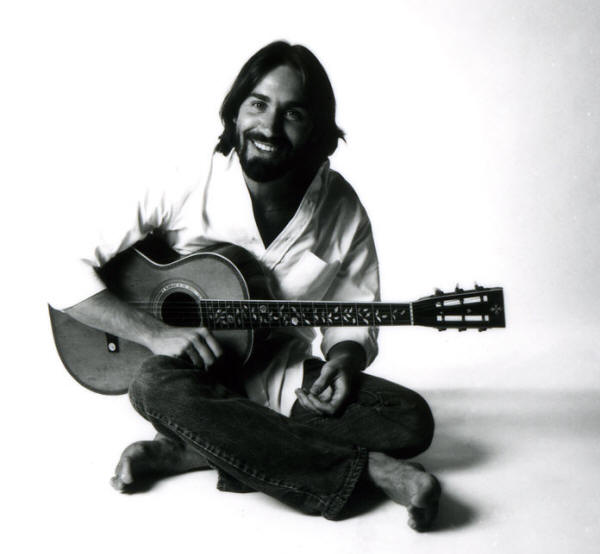

[Cover art and lyrics courtesy of http://www.danfogelberg.com; photograph of Dan Fogelberg courtesy of Andy Katz & Andy Katz Photography, used by permission]

Fathers and sons. That's some heavy shit there.

Well, at least it's heavy shit for me because although I don't believe in god, that doesn't mean I don't have a sense of my own spirituality. And that sense is never greater than when my thoughts turn to my father—even 24 years after his death.

I was fortunate to gain a sense of closure before his death, our eyes having a conversation while I sat at the foot of his deathbed the night before he passed. I'm not positive what told me it was that night or never for us to settle our differences, but it could have been what happened when I walked into his hospital room that night.

Please understand that my father was ill for most of my life, although it rarely stopped him from opening his paint store at 8 a.m. sharp every damn day. Even when dragging the "Texas condom" he had to wear as the result of an unsuccessful prostate operation and the hernia belt he needed because surgery for that malady was not something he wanted to do, he always got his key in the store's lock right on time. So when he had to sit in a hospital bed, in breathtaking pain for the nine months before he mercifully died, I was as used to the visitation routine as I was to the punctuality I inherited from dad's duty in opening the store on time. What I wasn't used to, was the medical community trying to improve its mortality rate, regardless of the patient's pain.

You see, first the doctors amputated a toe, to try and curb the gangrene he had developed from the many years in which his arteries had hardened. Then, they cut off his foot. And then, it was his leg. But before they took his leg, he looked at me and my brother—ten years my elder—and made us promise this would be it. So when the doctors, quite predictably, wanted to take his other leg too, I told them, "No way." And since his primary doctor saw the look in my eyes when I said it, he agreed—probably because he didn't want to be body-slammed to the floor, which is what would have happened if he tried to usurp my directive.

So each night I visited during his lengthy plunge into death, the routine was predictable. First it was that hospital smell, that antiseptic smell that is an unmistakable horror for the olfactory memory. Then I'd make my way to his room, which was easier to find by following the sound of my father's screams and cries. I don't think there's a drug that could have curbed the kind of pain he endured.

But on that last night, there were no cries, no screams. When I got to his room that last night of his life, he was sitting straight up, holding court for my brother and mother. And when I walked in—despite my father rarely, if ever, using gutter language—he looked at me and said, "Fuck you." We all laughed so hard, I thought I was going to spew an organ. Dad was his old self, cracking jokes and working the room so well, it would have been downright stupid to try and pry him from the podium.

Eventually, though, he slowed down and slumped into a drug-induced slumber so peaceful, it told me not to leave quite yet. So when my mother and brother left, I took a seat at the edge of his bed. That's when we had that conversation with our eyes, him gazing a look of acceptance while I conveyed how much I loved him despite our differences through the years. He would close his eyes and then open them with a look of love I knew was forever. I was lucky for that opportunity because when we got The Call the next day, it was like I already knew he had died. I knew because he had told me he could fight no longer, with his eyes the night before.

And to this day, the spirituality I feel is its strongest when thinking of my dad. So when I listen to Dan Fogelberg's beautiful homage to his father in "Leader of the Band," I fully understand what he was going through when he wrote it.

An only

child

Alone and

wild

A cabinet

maker's son

His hands

were meant

For

different work

And his

heart was known

To none --

He left

his home

And went his lone

And

solitary way

And he

gave to me

A gift I

know I never

Can repay

Well, my father wasn't an only child, having a younger sister. But he had a streak of wildness too, although he wasn't generous with details. I think his father lived on the other side of life, where grifters and con men lurk. Dad, therefore, had no love lost for his father and changed his name from Cohen, to something close to his mother's maiden name, which was Rudman. But he had a little flair, he did, so he changed the "u" to an "o," thus Rodman was his new name. And I've tried to wear it proudly, though my successes haven't always outweighed my defeats. Regardless, my father took the trouble to pick his new name carefully, so the least I can do is rise from those defeats and use it on everything I have ever written. Everything. And the "gift I know I never can repay?" The gift was him—the honesty he taught by chasing a customer out to the parking lot because he had mistakenly short-changed him by a nickel ...the example of knowing there is no substitute for hard work ... the cost that comes with living in a great country, the one that was paid every April 15 when he told our accountant to "just pay it," instead of taking advantage of the latest tax loophole ...and yes, the courtesy and respect paid to others by being punctual. These were the gifts I can't repay—not empty words in an old book read aloud on a specific day each week, as though honesty, hard work, responsibility and courtesy needed an owner's manual.

My father wanted to be an accountant, but was 19 years old when the stock market crashed and The Depression followed. If you know someone who experienced the 1930s at such an impressionable age, you know what I mean when I say my father wasn't one to give up a job, take risks with money or buy something he could rent. Heck, my father had so much Brooklyn in him, he never bothered to learn how to drive a car, his mass-transit life burned into his brain. Fortunately my mother could drive, so she had to answer that early call of opening our Maplewood, N.J., store too.

That dang store. Much of my life still hangs from its shelves of paint cans I can't forget no matter how hard I try. It had an unmistakable smell too—that paint and hardware smell that's dissipated in this time of big-box stores that have driven the small mom-and-pops out of business. It was a good smell, though. It was the smell of where I could find my father selling paint and my mother manning the wallpaper department. It was the smell of home, for all my school-age life.

However, it wasn't like my father owned a paint store right after college at CCNY (City College of New York, now something I don't know or care to find out). He did a little of this and that until, at 31, Pearl Harbor happened. Dad was a little old for the army, but he enlisted anyway. A pre-cursor to the rest of his life, though, saved him from near-certain death: Every time he was about to be sent into action, the army found something else wrong with him. Once, it was his third-degree flat feet (I have no idea how he marched with those feet) and another time it was something else I don't know about. And each time, the fellas with whom he was about to go to war, were wiped out. So the physical problems that defined his life during mine, were once a blessing in his.

And what did he do with all his state-side spare time? He took the pay of every G.I. who dared to challenge him at pool. And the extra money he made hustling pool (I guess it's impossible not to inherit something from your father, whether you want to or not), came in handy when he met my mother and married in 1943. Their stories from those early years always centered on my father and what a character he was.

He had a bit of absent-minded professor in him, sometimes bypassing the trash can when finished with his army meal, taking the tray all the way back to his bunk. He also had a bit of sketch-comic in him too, using chalk to outline where the furniture would be when they could afford it. He outlined a couch and a couple of tables, and my mother was so taken by the humor and sentiment she told the story approximately 3,000 times. Another famous army story was when he took the nameplate from the lieutenant's desk and wrote "Bucking for captain" on it. When the lieutenant found out who did it, he confronted my father, who replied, "I have a perverted sense of humor." The lieutenant just muttered, "Yeah, you're perverted alright," and walked away. And his pool exploits were fodder for conversation all-too-many-times, as well.

In fact, my brother and I heard about what my dad could do with a pool cue so many times, we got to the point of rolling our eyes. We even got to the point of doubt because we couldn't afford a pool table and dad never went to bars, where maybe they had a table and we could test the truth of his stories. In 1980, though, I was living in the Bay Area and selling stereo at a high-end shop in Palo Alto. At the exact time I was to be in New Jersey for the family version of celebrating my first of two marriages, my brother took delivery of a pool table and we could finally see if dad was all that. My father was 70 years old and hadn't picked up a cue in 35 years, but he went to my brother's basement and ran 45 balls in a row. My brother and I looked at each other with a "Holy shit" look I can't remember ever having before. And dad? He just smiled. It was that same kind of "conversation with our eyes" that would later announce his imminent death. But this time, it was dad saying "I told you so" with his eyes and me saying, "I will never doubt you again" with mine.

A quiet

man of music

Denied a

simpler fate

He tried

to be a soldier once

But his

music wouldn't wait

He earned

his love

Through

discipline

A

thundering velvet hand

His gentle

means of sculpting souls

Took me

years to understand

That's some beautiful writing. I couldn't think of that "thundering velvet hand" line, if I spent the rest of my life at a keyboard—without bathroom breaks. My father was also a soldier once and I've told those stories, but it's the occupation of Fogelberg's father that made me do a little research. At first I thought "his gentle means of sculpting souls" meant he was a psychologist. At what else do you sculpt souls? But liner notes from a four-CD collector's set released in 1997 and written by singer/songwriter/author/journalist/photographer/kick returner Paul Zollo (OK, just wanted to see if you were paying attention ...so I made up the journalist part) provided an answer far more profound: Lawrence Fogelberg indeed was a band leader. I shit you not—lyrics without a hidden meaning. What will they think of next? True advertising? So the simpler fate denied was Dan's father not being able continue his dream, as opposed to never tasting it at all. In his case, raising a family meant the more tame avenue of teaching music and leading high school bands. It wasn't Tommy Dorsey, but it had to be better than smelling turpentine for 30 years.

I remember being surprised when my father once said, "You think I wanted to sell paint my whole life?"

I was 19 when he said it and living my own dream of being a sportswriter, leaving Penn State after a year spent on the daily student newspaper and not more than a few hours in classrooms, confident I had all the practical experience I needed. When I announced my intentions of dropping out at a family dinner, my mother's head exploded—as much from the embarrassment she would endure from the judgments of her older sister, as anything about me directly. My father, though, said virtually nothing, silence sometimes being the best communication. He knew I'd make it work. Once again, it was that conversation with our eyes, him saying, "OK kid, let's see what you can do," and me saying—with both my eyes and my voice—"I can do this. You'll see. I can do this."

And do it, I did, landing a job as sports editor for Worrall Publications, which had four weekly newspapers in and around my home town that shared the same sports section. My father's confidence came to fruition and he was proud, whether he said so or not. In fact, I once caught him showing off my work to a paint company rep, when he didn't know I was in the store and witnessing what he was doing. When he realized my presence, he stopped, put down the paper and nodded to me. I caught him in a moment of pride and he was man enough to admit it.

But how' bout my father's dreams? As stated earlier, he wanted to be an accountant—and boy, could he do numbers. He would deposit checks weekly and have to count them up on a deposit slip, adding 20 or 30 four or five-figure numbers at a time, in his head. When calculators were invented and then came down in price to be affordable, we all encouraged my father to use one. He got so tired of it, he challenged me to a race: him against my calculator. Do I really need to tell you he beat me three times in a row and had an accurate total each time?

He would've been a great accountant.

A couple of years after getting married, though, the war was over and the country no longer needed the services of a pool-hustling private with flat feet. And with my brother being born in 1946, my father had the family duty his own father didn't fulfill—and there was no way he'd fail as well. So when he got a job selling paint, that became his profession. And when he got the chance to own a store, he took it, sealing his occupational fate forever. It was that Depression-Era sense of family duty that meant he would take the sure thing and not stop working to take the chance of following his dream. And the fact I lived mine—although once a source of great pride for me—has become a bit of an embarrassment, given dad never got the chance to live his. I guess every achievement comes with a price ...if you think about it long enough.

The leader

of the band is tired

And his

eyes are growing old

But his

blood runs through

My

instrument

And his

song is in my soul —

My life

has been a poor attempt

To imitate

the man

I'm just a

living legacy

To the

leader of the band

I hear ya, Dan. I hear ya even though you were taken from us too early, victimized by cancer before we could hear more about the soul your father passed to you. But at least you lived long enough to write about it and for that I'm highly grateful. I'm grateful because we have so much in common on this subject. When I'm down, I think of what my father would do; I listen to your song and think, "What would the old man do?" Well, I know damn-well what he would do: get off his ass and get to work. So when I'm down, I talk with my father, and then, I usually wind up at a keyboard—the same as you did, Dan, although your keyboard was connected to a piano.

Dan Fogelberg [Photograph by Andy Katz, Andy Katz Photography; used by permission of the artist. See http://www.andykatzphotography.com.]

Dad, like many from his time, wasn't one to show his emotions freely. But there was a day—a day I'll never forget.

I can't name the date, other than to say it happened at summer's end, after graduating high school in 1974 and as I was about to begin college at Penn State. At the beginning of that summer, my future was about to unfold and I had it all planned: Graduate college, land a sportswriting job at a major newspaper and spend the rest of my life in gleeful accomplishment. But as John Lennon said, life is what happens while you're making plans (perhaps my grand-prize winner for things I wish I had said).

At the beginning of that summer, I was holding four jobs. I was working at a convenience store, umpiring Little League, selling classified advertising for the Italian Tribune (based in nearby Newark and run by the father-in-law to one of my brother's friends), and of course, working in dad's paint store. But soon after graduation, things began to unravel in the most horrific of ways. First, dad had his third heart attack and was hospitalized for an extended time. That meant I had to drop the convenience store and Italian Tribune gigs, to help my mother in the store.

I assumed most of dad's role of buying and selling paint, while mom took over the bookkeeping and continued in her role of selling wallpaper, along with a part-time wallpaper saleslady dad had hired several months before. Then, my mother had to be hospitalized as well, with a severe gastrointestinal disorder.

This development—illness for my mother—was a new one. For all my life, she was a rock. She always helped out in the store because, well, that's the way-of-life in a retail family. And while dad had his repeated health problems, mom was always around to pick-up the slack. But with mom joining dad in the hospital, I had to drop the umpiring as well and work more hours in the store, taking over the bookkeeping.

Then, when I thought it couldn't get any worse, our part-time wallpaper saleslady broke her hip, putting her out of commission as well. Oh, and for good measure, my only brother was pretty much out of the picture as well. He was ten years older than me and recently had his first child. During that summer, he had his own family to take care of and was trying to build his own career in finance. So all of the sudden, I was it.

Everyone in the family—including my mother and father—told me to close the store; that it wouldn't be possible for an 18-year-old kid to run the entire operation. I said no way.

The store was fairly big in size, for a mom-and-pop operation. It was located on Springfield Avenue, the main commercial thoroughfare in Maplewood. As you walked in the front door, the wallpaper section was a separate showroom, on the left. The main sales floor was mostly paint shelves, with various hardware items and painting accessories, like brushes and rollers. In the very back was dad's desk, which always looked like a bomb had dropped on it. Organization was not my dad's strong suit. I always had to keep my pristine copy of "The Sporting News" away from his proximity, for fear of him writing a paint order on it.

There was also a warehouse section off the main sales floor, which held additional paint inventory and a small back room, where dad allowed me to have a clubhouse when I was eight years old. But I wasn't eight years old anymore and that summer of '74 drove the point home with a jackhammer.

The biggest challenge off-the-bat was the wallpaper section, which had become the most profitable part of the store. Selling paint was easy: Just show the customer the color charts and get the cans off the shelves. But wallpaper was much more difficult. If somebody walked in and said, "I want a wallpaper with pink elephants on a gray background," you had to know which of 500 sample books to show her or him.

So, to familiarize myself with the wallpaper sample books, I would go into the store on Sundays (the only day the store was closed; a concession my dad finally made after his second heart attack) and study each and every one of them. I then stored them by categories I created for ease of recollection: vinyl wallpaper for kitchens, good bathroom patterns, fancy wallpaper with felt flocking, the expensive cork wallpapers and so forth. A couple of Sundays later, I was good enough to get by.

Of course, there was the problem of two or more customers at the same time. So if I had a wallpaper customer at the front of the store and a paint customer at the back, I had to juggle the two (and keep one eye on our old-fashioned cash register). What I would do is give the wallpaper customer a few books to look at and then quickly attend to the paint customer. If the paint customer was a regular—such as one of the professional painters who bought from my dad—I could trust him to get what he needed, write down what he took and then send him a bill.

I did the bookkeeping at night, after the store closed. This mostly entailed making bank deposits, cutting checks to suppliers and billing the regular customers. The bank understood the circumstances and allowed me to endorse business checks—that's the way it was back then. (Try and do that now; the bank president would look at you like you were from Mars.) In between all that, I had to accept paint deliveries, stock the shelves, order what we needed and so on.

Well, not only did I keep the store afloat, I actually improved our business. Dad had let the store flounder; he was 64, in ill health and getting clobbered by a big chain that had opened a few blocks away, two years before. Wanting to gain an advantage on the big boys, I took in two lines of paint the competition didn't have and sold the hell out of them. I made as many wallpaper sales as possible, offering discounts to entice customers. There were actually decorators who wouldn't allow their clients to buy wallpaper unless they bought it from me.

The paint salesmen who represented suppliers, such as the Paragon and Peerless paint companies, were stunned. A couple of them tried to talk me into forgoing college and taking over the store (they didn't want to lose a good customer). And to tell you the truth, I thought about it. The conclusion I reached was that if I had to delay college, I would—at least until mom and dad could return to work. Fortunately, it never came to that.

Dad recovered as the summer was drawing to a close and mom recovered shortly thereafter. Friends and family had told them what I had done during their illnesses and dad was going to be the first to return to work. For dad's return I had a big day planned. I worked frantically to clean the store and make it as spiffy as it had ever been. I waxed the floor, dusted the shelves and made sure all the painting accessories were properly merchandised. The rollers were sandwiched between the paint trays and buckets; the epoxy was merchandised next to the caulking guns. All the paint shelves were stocked, lined with one-gallon-cans that looked like tin soldiers at attention. The paint brushes were aligned perfectly on our angled display board, each clinging to their own clamp and ready for purchase. The 500 wallpaper sample books were in their right slots, my dad's desk was clean and all the bookkeeping was up to date. When all was said and done, I was exhausted. But I knew I had done a good thing; I knew there wasn't one thing more I could have done.

And then dad walked in.

My father was a great guy, but he wasn't one of the most affectionate people in the world. I knew he loved me and I knew he admired my high grades in school and modest accomplishments in athletic pursuits, but he never outwardly showed it.

But after walking in that day, he stopped about ten feet inside the front door and looked around. He had been told of my work, but he obviously didn't realize exactly how much work I had put into things, other than opening the door in the morning. He took his time looking around the store from a standing position. He saw the store looking as good as it ever had at any time in his 17 years of ownership.

Then, he looked at me. I was standing a few feet away, waiting to see his reaction. He opened his arms and invited me in. He hugged me like he had never hugged me before. He didn't say anything, but the tears in his eyes told me all I needed to know. We hugged for what seemed like hours, though I'm sure it was only a moment.

Finally, he let go, but let me tell you something: I can still feel that hug today.

My

brother's lives were

Different

For they

heard another call

One went

to Chicago

And the

other to St. Paul

And I'm in

Colorado

When I'm

not in some hotel

Living out

this life I've chose

And come

to know so well

I've mentioned my brother. Now I need to mention I haven't spoken to him or any family member in 17 years. I have my reasons and have taken full responsibility for the fall-out, which has been about what I thought it would be: I'm the crazy uncle nobody mentions (other than as dinner fodder, I assume, for the small souls of my brother and cousins ...they wouldn't say shit to my face because they know I can beat the crap out of all of them). So did my brother hear "another call?" Not really—it was I who heard another call and although I know my father wouldn't like me and my brother being estranged, I know he would understand my reasons. And you know what? He might have done the same thing himself ...if he didn't have a family to support ...and a paint store to open.

Alison and Danielle.

Those are the names of the two people I miss most, as a result of my 17-year family estrangement. And now that I'm fully comfortable with my lot in life, I can write about them openly for the first time. They're my nieces and it's Danielle who I'd like to speak to before I die because she's next-in-line for the spiritual connection to my father.

I guess a little history might help. When I say I have my reasons for the estrangement, it's not that I want to keep them private. As I told Positive Feedback Publisher David Robinson when I started here, I'm to a point in my writing life that I'm not interested in "easy." I want to take as many chances as possible and for this space to be as personal as possible. Anything else is just bullshit, and for that, I may as well go back to writing for newspapers. But to do justice to my estrangement—something I've come to hold near-and-dear—I'd need a goodly portion of a book to explain it. And fact is, I wrote a book that contains those reasons. So if anybody really wants to know the Full Monty, I'm easy to find. I can, however, provide you with the camel's proverbial straw: I wasn't allowed to speak at my mother's funeral, as I had done so touchingly for my father seven years before ("touching" wasn't a word of self-congratulation; it was the word-of-choice among funeral attendees after hearing what I had to say that day).

There were many things I didn't like about my mother, but she was indeed my mother and I loved her. Not being allowed to speak at her funeral became Exhibit A in how my family didn't respect my beliefs, despite demanding the reciprocal from me. In a truly strange turn of circular logic, improving myself in rehab justified the censure—even though I was in the full-fledged throes of my addiction during my father's funeral and without the admirable attempt at changing the only personality I was issued upon leaving my mother's womb. And you know who enforced this decision? My frickin' sister-in-law—that's right: not even a blood relative. And what did my brother do as his wife led the panzer attack? He sat his pussy-whipped ass down and didn't say one frickin' word. Not one.

Alison was a teenager when I said good-bye forever and I don't think I can overcome whatever impressions she already had of her drug-addict uncle and whatever lies my sister-in-law has said about me in the time since. But Danielle was younger and couldn't understand it, so maybe I have half-a-shot at making the other side of the story stick with her. And after that, maybe I can explain the connection to my father.

There was a year between me returning to New Jersey after six years in California, and dad being hospitalized until his death. During that year—from early-1983 to early-1984—I saw my dad inter-act with my nieces several times. And although he clearly loved Alison, he had a special sparkle every time he saw Danielle. He talked about her frequently and always looked forward to his next chance to hold her and look into her eyes. I saw that look and knew it well; it was the look of love and acceptance—the same look I got after turning a crazy idea into reality.

It was the look I've been trying to convey throughout this song-story ...the look of "I love you, regardless of whatever crazy shit you do." Whether it be dropping out of college and then getting the same kind of job I would have gotten had I stayed three more years for a sheepskin to hang on my wall; or chucking that career, to move to California and sell hi-fi for a living; or coming back to New Jersey intent on making the unusual jump from retail to a supply-side job and getting that done too, making it all the way to Eastern Regional Sales Manager for BSR/ADC/dbx, then Sansui, then Phone-Mate; or returning to newspapers 14 years after working at one and making that a success as well. Dad saw most of this and gave me that special look as I accomplished whatever my mother thought was impossible—that look of "I love you and I knew you could do it."

He flashed that look to me and Danielle. He might have flashed it to others, but I never saw it. That's why I have to speak to Danielle. There's much to talk about, but the connection to her grandfather is the main thrust.

So, to Danielle: If you're out there, like I said—I'm easy to find.

I thank

you for the music

And your

stories of the road

Thank you

for the freedom

When it

came my time to go

I thank

you for the kindness

And the

times when you got tough

And, papa,

I don't think I

said "I

love you" near enough

Sometimes I get pissed off when a songwriter says in a few words what it takes me thousands to convey. In this case, though, I'll just accept it as Dan Fogelberg being better at his craft than I am at mine. Decades have passed since dad died and while I revel in our connection, I've also come to realize I can't be the best at everything—and he's fine with that. And although, like Dan, I know I didn't say "I love you" near enough while dad was alive, I've said it enough times since for him to get the message, our spiritual connection being the telephone line to infinity.

I guess above all, my father was a real character. I've told you some stories, but with a guy like him the stories could go on forever.

For instance, he would regularly lose track of where his false teeth were, given the frequency with which he would take them out. I can't tell you how many times we had to re-trace his steps, to find his teeth. Did they drop out of his shirt pocket when he bent down to get the New York Post at the newspaper stand? Did he drop them into the bathroom toilet? Did he leave them in the car somewhere? And then, there was always my favorite location of discovery: in his mouth.

For good measure, how 'bout this combination of interests:

a) geometry, as it applied to both billiards and golf—the latter a sport of extraordinary interest to him, despite him never so much as holding a club;

b) a voracious newspaper reader who bought every New York daily, as well as a religious reader of celebrity news, as presented by that bastion of journalistic integrity, The National Enquirer; his supposed knowledge of celebrities from bygone eras was another eye-rolling affair among distant relatives, who once in the mid-1960s called him to the carpet when he mentioned a silent film star named Bessie Barriscale; the lead Doubting Thomas was a physician we'd see occasionally at extended family affairs, who couldn't stop laughing over dad trying to sneak one by him, particularly one with such an absurd name; he stopped laughing a month later when my father mailed him her obituary;

c) a pornography collection that would make Larry Flynt blush;

d) an absolute insistence on watching the Oscars every year, despite him not seeing any of the nominated movies—either previously or subsequently;

e) as big and knowledgeable a boxing fan as I've ever met;

f) an absolute fashion plate who enjoyed dressing to the nines—even though he rarely went out, meaning he'd often wear $500 ensembles (in 1965 dollars), while mixing custom paints at the store;

g) apparently, he was an ace roller skater ...after the pool thing and Bessie Barriscale, I no longer doubted him on this either.

And I haven't even mentioned the eating habits I acquired from him. Dad prided himself on eating things that would make my mother squirm: chocolate-covered ants, anchovies straight from the can, kippers that would make the house smell for days, etc. And since I could always eat twice my body weight, strange food was another form of our father-son bonding. I ate so much, my dad was fond of saying, "I'd rather clothe him than feed him." But he got a kick out of my adventuresome attitude towards food, which was quite unusual for a young kid.

When I was a teenager, we used to go to a tiny, hole-in-the-wall restaurant in Newark, called "The Seacrest." The restaurant only had about eight tables, but they seemingly made anything that could be found in the Atlantic Ocean. The menu was on the walls, written with Magic Markers on those pieces of cardboard that used to come with laundered shirts. Everything was a-la-carte and made one order at a time, so the routine was to order one dish, and when it came to the table, order your next one. We'd always start with a bucket of steamers (soft-shell piss-clams—just take a look at the worm-like tail and you'll know what I mean), then maybe have a plate of smelts, then some eel, then who-knows-what, until we were finally full two hours later.

The only problem was that the place was so small, weekend lines would often stretch around the corner. One day we were particularly hungry and decided we'd call-in a favor, to get seated. My brother was with us and his best friend from college had married the daughter of the Good Fella I mentioned earlier—the one who published "The Italian Tribune" and for whom I sold classified ads before having to run the paint store. The publisher was known around Newark as "Ace," and everybody knew who he was, if you get my New Jersey drift. So faced with the long line to get in, we went to the front of it, got the attention of the owner and said, "We know Ace." The owner said, "You know Ace? Hold on, one second." He then turned to a table-of-four and said, "You're finished, right?" The people weren't quite done with their meal, but agreed anyway.

Why? Because we knew Ace.

The stories could go on forever, but it's time to bring this song-story full-circle, with Fogelberg's last stanza and one of the toughest questions in life: What is love? I'm not the brightest guy in the world, but I'm going to take a stab at it: Love is acceptance. My father accepted me in a way my mother never could. For my brother, it was the opposite, but I am definitely dad's boy. And his acceptance was always better stated with his eyes than his words. I know this because of the look I still see in my father's eyes after I manned the store in his and my mother's absence, or when I went from drop-out to sportswriter at age 19, or when I went from retail hi-fi to supervising 50 reps as a regional sales manager. I know it every time I hear Dan Fogelberg sing "Leader of the Band."

And I know it because of the conversation we had with our eyes the night before his death. But like Fogelberg's homage to his father—a tribute that, according to those 1997 liner notes, transported Dan back to the age of 4 when he first experienced a life without fear, facing his dad's big band while standing atop a box, wielding the power and majesty of a baton, his tiny hand guided from behind by that of his father—this is not a sad story. This is a story of glorification, a story of how spirituality extends the life of someone with whom you connect forever.

So dad, Happy Father's Day, on this the 24th year of our second life together. I look forward to the next 24 or however many it takes for me to join you in our third life. And just as Lawrence Fogelberg could count on Dan to bring the baton last year when cancer placed its own call, you can count on me to bring a good pool cue because I could really use the lessons.

Mike Rodman, an Associate Editor for Positive Feedback Online, is a free-lance writer and author who lives in Fayetteville, Ark. He can be reached at: [email protected].