|

You are reading the older HTML site Positive Feedback ISSUE january/february 2008

Solo Piazzolla:

Manuel Barrueco, TonarMusic #70715 (2007):

An Essay/Review [All images courtesy of the Barrueco website http://www.barrueco.com, and are used by permission. For specific photographic credits, see http://www.barrueco.com/pages/photos.]

Stature Manuel Barrueco was born in Cuba in 1952, and migrated with his family to Miami. He lived for a while in Newark, New Jersey, and finally settled in the Baltimore area so he could continue his association with his alma mater, the Peabody Conservatory, where he studied, has been Artist in Residence, and is on the faculty. Barrueco was bounced around by one of the tsunamis of history, in this case the Cuban revolution and the rise to power of Fidel Castro, which brought social dislocation to many Cuban families. He seems to have transcended history with a kind of stoicism. Barrueco is an outwardly even-tempered man who, I think, finds expression of his inner states through his music. As it was inevitable that he would take on the music of Joaquín Rodrigo, it seems inevitable Barrueco would also record the guitar music of Astor Piazzolla. In a very profound way, I think they are soul brothers, linked by expatriation, Spanish culture and music, and in this case—by the tango. The tango is an "Argentinian dance, possibly imported into America by African slaves, performed by couples at a slow walking pace to music in simple duple time and with dotted rhythm like habañera. [Tango] became a popular ballroom dance c.1914. Some composers have used the tango in their works, e.g. Walton in his suite Façade." The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music: Michael Kennedy, ed. (1980). Tango has changed with the change in social mores concerning public dancing. More about this, anon. During the past thirty-four years Manuel Barrueco has continuously gained in stature, beginning when he first burst upon the classical guitar world in 1974, when as a 22 year old he received the Concert Artist Guild Award. His youthful playing was startlingly masterful (See his 300 Years Of Guitar Masterpieces: Vox Box #3, recorded in the ‘70s and re-released on three CDs in 1991). He has continued to mature, and this was especially true through the late nineties (See especially his Concierto de Aranjuez, with Plácido Domingo, conducting: EMI, 1997). Now thought of as something of an icon, he is revered by other guitar players for his suave musicianship, technical excellence, and impeccable taste. He is also beloved by his world-wide audience for his carefully modulated expressions of beauty and passion. To his generation, Barrueco is now as Andrés Segovia once was: revered and beloved by his generation. To claim Barrueco as today's Segovia might be overstated for emphasis, but only slightly: Segovia is undeniably the father of the classical guitar, and there can be no other. But Barrueco's recording of Joaquín Rodrigo's Concierto de Aranjuez (to guitarists as Beethoven's Violin Concerto is to violinists) was cited as "the best recording of that [often-recorded] piece" by Classic CD Magazine. (See also https://positive-feedback.com/Issue23/dudious_aranjuez.htm.) Barrueco was quickly recognized as "one of the best classical guitarists on the planet" (by Audio), and as having produced "the best-sounding guitar records of any major artist" (by American Record Guide). As Manuel has gracefully grown into his role as "the man" of classical guitar, esteemed musicians like The King's Singers, tenor/conductor Plácido Domingo, flutist Ransom Wilson, clarinetist Sabine Mayer, bass violist George Hörtnagel, as well as jazz guitarists Al Di Meola, Steve Morse, and Andy Summers, were eager to record with him; and contemporary composers Roberto Sierra, Michael Daugherty, Toru Takemitsu, and Gabriela Lena Frank have been writing pieces for him. Though the compositions on this album were written by Piazzolla some years ago, and were not commissioned for Barrueco, with the program of this solo recital of guitar music by "The Great Astor" we can take the measure of Manuel Barrueco, the artist and the man. He doesn't let us down. Astor Piazzolla But before that, a thumbnail sketch of Astor Piazzolla (1921-1992). Astor Piazzolla was born in Argentina, to Italian parents, and raised in New York City from age three, so he was fluent in at least three languages (like Barrueco). His father gave him his first bandoneón, an accordion-like instrument, when he was nine, and Astor began to show his considerable talent for music early on (like Barrueco). As a teenager (1937) he was good enough to make his way to Buenos Aires to play tango music in the many cafes and cabarets there. While Piazzolla was in his twenties he was inspired by the music of 20th century greats Stravinsky, Bartok, and Ravel, and he began incorporating many of their devices in his compositions. By virtue of winning Argentine competitions for composers, when he was 33 he was able to journey to Paris (in 1954) to study with the great teacher, Nadia Boulanger. On hearing him play, Boulanger convinced him his musical soul was more deeply intertwined with the tango than with his musical idols, and encouraged him to develop his nuevo tango music. He did this largely on his own, incorporating many figurations of classical music (largely Bach) and jazz into his new compositions, calling upon his own new harmonies, but featuring rhythms and tempi that remained distinctly the tango. The witty Piazzolla repeated often and slyly that the bandoneón he played was developed for church music in mid 19th century Germany, migrated to the brothels and cabarets of Argentina by the early 20th century, and by the late 20th century had moved into the world's concert halls. This makes Nuevo Tango, like jazz and Bossa Nova, a music of the people, filled with passion, sorrow, joyful dance, and the blues. In Piazolla's ensembles, emotions were given room for a range of improvisational expression by his band members. In the hands of lesser composers the tango had reached a predictable, harmonically simple, rhythmically rigid, cliché ridden, dead end. Astor Piazzolla is generally credited with having resuscitated the tango upon his return from Paris, and having brought the form to its current renaissance as Nuevo Tango. His contribution, bringing jazz-like improvisation, classical figurations (such as the fugue and the passacaglia), and modern harmonies to the tango, made him one of the composers whose work blurred the lines of musical categories, and brought him recognition as a major figure of late 20th century music. If you are a musical purist you might think of Nuevo Tango as chamber music. If you feel musical categories ought to be more inclusive, you might think of it as jazz, with encouragement for improvisation. In any event, Astor Piazzolla is considered a major innovator and a large figure of recent music. [To learn more about Astor Piazzolla, Google him. There is a biography of his life, and a discography of his work, in Wikipedia at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Astor_Piazolla.] The Music If you haven't caught on yet, I ought to confess that I am a fan of both Manuel Barrueco and Astor Piazzolla. I have a handful of CDs of music by each of them. I heartily recommend Barrueco's Vox Box of 300 Years of Guitar Masterpieces, Vox CD3X 3007 (1991) to hear Barrueco's youthful take on Bach, Albeniz, Scarlatti, Cimarosa, Paganini, Giuliani, Granados, Villa-Lobos, Guarnieri, and Chavez – a three-hour (3 CD) program of solo playing; as well as his more mature program of works by Joaquín Rodrigo, Concierto de Aranjuez, EMI CDC 7243 5 56175 2 1 (1997), with a symphony orchestra. He has also recorded over a dozen CDs for EMI that range through one album that is mostly Mozart, Manuel Barrueco Plays Mozart & Sor, EMI CDC 7 49368 2 (1988); and another of more modern composers, Manuel Barrueco Plays Brouwer, Villa-Lobos, & Orbón, EMI CDC 7 49710 2 (1989); as well as covers of Beatles' compositions, an album of jazz with some well-known jazzmen, and his takes on classical compositions (some written for the guitar, and others transcribed for it), sometimes featuring a variety of accompanying groups, and sometimes featuring Manuel playing solo. I also have on hand performances of Piazzolla's music ranging from solo guitar, Baltazar Benitez: Music of Astor Piazzolla, Canal Grande 9322 (1984); to duets for guitar and violin, Atis Bankas v., and Simon Wynberg g.: Piazzolla's Histoire du Tango, et al; Fidelis FR002 (2002); a string quartet, with Piazzolla on bandoneón, Kronos Quartet: Five Tango Sensations, Elektra Nonesuch 979254-2 (1991); an album of arrangements for various small groups led by a violinist, Gidon Kremer: Hômage à Piazzolla, Nonesuch 70407 2 (1996); another album of arrangements for various small groups led by a cellist, Yo Yo Ma: Soul Of The Tango, Sony SK 63122 (1997); and a 1984 concert by Piazzolla's own band, Astor Piazzolla: The Central Park Concert, Chesky JD 107 (1994). These speak for themselves, and I recommend them all for differing refractions of the music. For example, it is amazing what timbral shift a cello adds, or the counterpoint a piano brings, or what heft a bass viol can deliver, and how much room for improvising Piazzolla gives his own band. Forgive me, again, as I digress, but multiple recordings demonstrate the technical and emotional range of a composer's music, particularly as compared to being played by a solo guitar. The CD for review is the new one (2007) by Manuel Barrueco titled, Solo Piazzolla. It begins with Le Gran Àstor's ("The Great Astor's") pieces named for the seasons "Winter" and "Summer." If Vivaldi could capture the feeling of passing seasons around Venice, why shouldn't Piazzolla offer his impressions of the seasons in his Estaciones Porteñas (The Four Seasons: 1968) as experienced around Buenos Aires? To begin, Barrueco offers Invierno Porteño (Winter) with a lyrical, dreamy, 7 minute bout of wistfulness suited to the music. I find it particularly touching today, New Year's Eve, recovering from my annual winter head-cold and already yearning for spring. Manuel follows with a pyrotechnical opening for Verano Porteño (Summer) that is a fanfare of his own devising, before he gets into the shorter, 4.5 minute, piece. This turns into a microcosm of Piazzolla's style, in which a rhythmic tango figure is juxtaposed to a long and beautifully phrased melodic line. I couldn't keep myself from comparing the ways that Barrueco (2007) and guitarist Baltazar Benítez (1984) each approach this music. Benítez accents the bravura elements of the playing, while Barrueco plays the two different (fast and slow) sections with wider variation in the tempi, mostly low-balling the piece, playing both sections more slowly, more thoughtfully. This approach seems to highlight various sections in the score, causing the audience to listen harder, as when veteran actors forego the shout and drop... their... loudness... and... speed ... to... heighten... the... emotion. But as recording engineering has advanced in the past twenty-three years, we don't have to work all that hard. Moreover, the Benítez reading seems to have been recorded in a larger venue with more reverb and a longer decay time. This is more atmospheric, but blurs the fast notes a tad. The newer Barrueco version displays greater clarity to me (listening on headphones), is more immediate, and moves the audience forward, which makes it easier to pick up on the nuances. But that's only my take. Benítez is a first-rate guitarist in his own right. It seems to me that he recorded his album of the Piazzolla solo guitar music when he was about 35, while Barrueco recorded much the same program when he was 52-53. I happen to prefer Barrueco's more mellow approach myself, being an older dude. So I prefer Barrueco's CD on two grounds: recording clarity, and musicianship or interpretation.

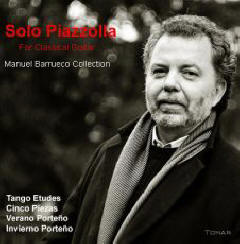

A Portrait of Manuel Barrueco (Photo: Arek Berbecki) The tango has moved considerably since it enjoyed its first flair of popularity. With the times' general relaxation of rules about "lewd behavior," dancing in the movies has become more suggestive and obviously sexy. This is mirrored in public dancing. There is a lot more obvious pelvic thrusting, and obvious sexual posturing allowed today than in the days of Arthur Murray dance schools, and in the movies of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Dance music, tango and otherwise, has likewise moved into this more "earthy" and explicit form of expression. In Astor Piazzolla's Nuevo Tango there is much smoldering and yearning, but it is always muted. To play an album of Piazzolla's music on solo guitar, any artist has to be tuned in to both the yearning and the muted, tragic quality of its expression, and be able to play the music accordingly. As the composer John Adams writes: The more time one spends with his music, the more the music's starling little perversities begin to reveal themselves. A loose, spontaneous tango will suddenly engage in a passage of carefully strategized counter-point that brings with it an ambience of controlled rigor to a music of otherwise boldly erotic lyricism. Piazzolla shares with the Brazilian Heitor Villa-Lobos a strong affinity for the sequential harmonic movement of Johann Sebastian Bach. These harmonic sequences have a sense of inevitability in the way they pull inexorably toward the cadence, and it is the core of Piazzolla's art to arrange—or to postpone—these arrivals in the most wrenchingly bittersweet of ways. It is as much as saying that you have finally arrived home, but home is no longer the same. Your house has been razed, and strangers now live in the neighborhood where you once played as a child. This seems a marriage made in heaven for Manuel Barrueco with his style of playing that is often described as "elegant," "aristocratic," or "sophisticated." Such words signal that he doesn't have to go for the bravura moment with quite as much "in your face" gusto as most other guitarists. We have come to recognize this quality and we call it having "good taste." There is no arguing that, whatever we call it, Manuel Barrueco has it. (For but one exquisite example, hear his Villa-Lobos Prelude No. 4.) He is able to capture the yearning and the sad modulating of desire in the music and play it so the two parts remain in tension one with the other. Easy to say, hard to do. Like Bach, Barrueco seems always to have understood how to do more than one musical thing at a time, a characteristic of his stylish guitar playing from the beginning. On the Solo Piazzolla album, in the collection titled Cinco Piezas (or, Five Pieces), Barrueco begins with a very atmospheric reading of Campero. Barrueco notes, this campero starts with an arpeggiated opening not unlike a baroque prelude. A milonga campera is a guitar-accompanied song, sung by rural payadores. These minstrel-like figures often accompany themselves on guitar and tell of patriotic acts of heroism, often by the Gauchos. They usually improvise on the decima, a 10-verse rhythmic combination. Piazzolla reduces this form to its essence, and Barrueco offers his insightful version. It is simple, and haunting, the kind of music that stays inside your head a while. Romántico, as its name suggests, is sensual and romantic. To achieve his tragico-eroticism Piazzolla uses the usual technical means, and Barrueco is able to draw from the music a sense of free flowing sensuality, nostalgic and open, a little sad, suggesting the tangos of the Forties. Acentuado, suggests that strain of tangos that employ heavily accentuated rhythmic figures. This sort of tango was the vogue when Piazzolla was playing in the cafes of Buenos Aires, during the Fifties. It relies on percussive effects and glissandos and keeps the guitarist busy. It fulfills the qualities of the milonga, and with all, it never loses the essential quality of tango. Tristón, from the same root word as triste, or sad, sustains the tragic air of a slow and majestic procession. The melody is making a procession of sorts, bringing something like "the unanswered question" to bear, and repeating it in various registers, in various chordal modalities, until it, overcome with its own tragic sense, comes to an end. Compadre is allegedly a parody of the tangos known as "compadritos" (a combination of a dancer, singer, and proud flamboyance). This is the kind of music that reminds me of the tangos where the dancing partners do mock battle while adhering to the tango form. If you try, you might imagine a pair of theatrical apache (Fr. for "hooligan") dancers beating up on each other in a state of heightened sexual tension.

(Photo: Arek Berbecki) Following are the final six Tango-Études, arranged by Barrueco, of which he writes: Arranging the Tano-Études was quite a different challenge. Piazzolla wrote these pieces for solo flute and so they are void of any kind of accompaniment. As opposed to arranging from the keyboard, where one is left with the task of having to remove notes from the original score that cannot be played on the guitar without leaving any visible scars, the task here is to add and fill in all that one suspects is implied, whether voices, harmonies, or accompaniment figures, always trying to stay completely in style and hoping that everything will sound as though it was written by Piazzolla himself. A difficult task, but it was fun and enlightening nevertheless. And Barrueco plays these new arrangements in such a way that it is hard to tell where Piazzolla ends and Barrueco begins. It is almost as if the two men, one fifteen years deceased, had collaborated (as Brahms and Joachim collaborated on the Brahms Violin Concerto). In any event, the album ends with Barrueco's act of devotion to Piazzolla, and to guitar music at large. It is an extraordinary series of pieces, very much in the tradition of Le Gran Àstor, ranging through all the technical and harmonic demands of his other guitar pieces, and generating more of his controlled tragic musical expression. I could go on, but I've nothing left to say, except this CD is a keeper. Again, in the words of John Adams: It is a rare musical mind that can elevate a single small musical form like the tango into an expressive vehicle of such depth and range. The impression we take away from experiencing these tangos is of a complete and indigenous native voice, one whose roots were as innately Buenos Aireian as Tchaikovsky's were Muscovite. We then learn with amazement that Piazzolla was far from being the homegrown phenomenon that his persona might suggest, but rather a highly cultivated musician, a student of the great French pedagogue, Nadia Boulanger (teacher of Aaron Copland and friend of Stravinsky), and a long-time resident of New York City. Piazzolla was a highly cultured composer of instrumental and theatrical music possessing a secure grasp of musical theory and the practical technique to realize his ideas. But his music flourished more naturally in the cafes and bars of the urban centers of Argentina than in any concert hall. For him, composing and performing were inextricably woven together. One thinks of Bach and of Ellington for models of a creative musician who saw little or no separation between improvising, composing and performing.

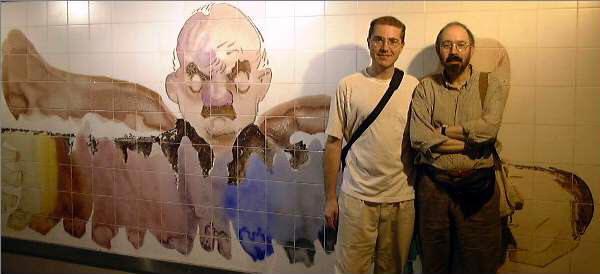

John Buckman and Cesar Luongo standing by the Astor Piazzolla mural in a subway in Buenos Aires (image courtesy of http://www.piazzolla.org) So, if this little essay has moved you, hop onto your computer chair, boot up your machine, and with controlled sadness, punch up your favorite vendor and order a copy of this album, Solo Piazzolla. You won't be sorry. This CD is special. Have I already mentioned that? Oh, well; the reader is instructed to disregard the final comment. Ciao Bambini.

|