|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 7 Positive Feedback Online Interviews: Steve and Janet Nugent of Empirical Audio (Photographs and image processing by Robinson) [In May of 2003 I interviewed Steve and Janet Nugent of Empirical Audio. A transcript of the conversation follows; it has been edited for clarity and brevity.]

Steve Nugent (foreground) and Janet Nugent (background) of Empirical Audio Robinson: Steve, you and I Steve Nugent: From the time I was a child with my brother, my only sibling, we made a lot of music together. We sang together. I played guitar from a fairly young age, and we would informally perform at times. Both of us discovered—or at least I discovered—that I am not all that talented. I am not a natural musician, but I love music and I loved both listening and making music. When I graduated from college, I found that I had enough money to start building a little audio system and proceeded over the years to upgrade that four, five, six times. In the last 10 years or so, one of my last upgrades was wires and cables. I did a lot of experimenting with cables. I decided that cables were expensive and the performance I was getting out of them was disappointing at best. I decided I could do better than this, so I started playing around with cables and doing some experiments. I started doing some simulations to see what works and what doesn't work with cable. That was where my head came from as far as audio goes. I love to just sit and listen to music. We have very eclectic tastes, I think, both Janet and I. We have a lot of different types of music. Janet also plays piano, so we each play an instrument. Janet, do you want to talk about your music experience? Robinson: Yeah, Janet, how did you latch up with this guy?!

Janet Nugent of Empirical Audio Janet Nugent: We met a long time ago. I was 16 and he was 17. Steve didn't mention this, but he played in a band. I also played in a band briefly, a very different kind of band. I played a little guitar. We both went to college and got our degrees and got our professions started. After that we got married. Robinson: What is your professional background? Janet Nugent: I went to school at University of Northern Colorado and got a teaching degree. It was what I always wanted to do and was happy to be able to fulfill that desire. I got to teach for 10 years. After teaching at the elementary level, I went into training and worked as a contractor with Key Bank, doing some training on mainframe software. Then I worked in a customer support role for a multi-processor software business. I did a little bit of managing properties that we had, and now I work with Steve on Empirical Audio. I am the PR person. Steve Nugent: She helps me craft the slogans and that sort of thing. Steve Nugent: Right out of high school, I went to college at the University of Colorado and got an EE degree, then went directly into large corporate America. I started with a company that competed with IBM on large mainframe peripherals, a company called StorageTech. I went into digital design. The interesting thing was, when I went to school, they didn't even teach microprocessors in school. Robinson: Microprocessors were evil! Steve Nugent: They were really new. There were no courses at school. Right after getting out of school, I had to really train myself in microprocessors. I built several from scratch, systems using wire-wrap boards and stuff that I got from Storage Tech. I sort of self-trained myself on that and a lot of digital electronics. I did a lot of digital electronic design, particularly interfaces, which are kind of applicable to audio because you are talking about interfaces that drive cables usually over long distances. They may or may not be treated as transmission lines. And lots of protocol definition, bus definition. If you do those kinds of things, it gives you a really broad understanding. If you do nothing more than design silicon, you never really get a feel for system design.

I consider myself really a system designer and not just a logic designer. I got to actually dabble in a lot of different aspects of digital design at the system level. After working about 10 years at StorageTech doing primarily tape controllers for big tape, the big reel to reel, vacuum columns, we went back east and I worked at Sperry Univac in Blueville, Pennsylvania. I worked in the actual building where the Eniac was invented. They had the glass cases of all the original pieces and photos. That was very interesting. There I did disk controller design. I managed a small group that did a disk controller and I did some of the design as well on that one. I only worked there a couple of years. That product was canceled and I started working on other things and it got less interesting. I started poking around to come back west. The east wasn't really where I wanted to live permanently. I dabbled around and looked at Mentor Graphics, Tektronix and Intel. Intel had an interesting group at the time, Intel Supercomputers. They did parallel supercomputers and a lot of really innovative things that other companies were not doing. I got involved with them and was hired on. I spent most of my digital design career there doing super computer design. In the super computer area, I designed the message passing back planes and the interface for two generations. One was the hypercube topology, and then the mesh topology for messaging passing, what is called "massively parallel" computers. I developed the cabling as well. These were huge machines that would fill an entire room. One of the machines that we built had 250 boxes, and each box was the size of a refrigerator full of what we called "node boards," which were computer nodes. There were serious problems with trying to send data across really large arrays of machine, and you couldn't have any degradation in the data. If you have done digital design, you know that the further you send signals, the more they degrade, even if you buffer them. We had to come up with clever ideas to make the machine scalable to really large sizes. That was where I came in. I have about 12-14 patents of new technologies to tackle the scalability issue of the massively parallel super computer. In fact, some of those technologies were used later in the Pentium series of computers by Intel after they got out of the super computer business. That division got converted to design server systems. They actually took some of those ideas that allowed us to do massively parallel and applied them to single compute nodes. It was really nice to see that technology live on and benefit Intel. Robinson: How long were you at Intel? Steve Nugent: I was at Intel 16 years. My last 5-6 years there, I did work in the micro processor group. I was the design team lead on the Pentium II cartridge. That was the first to really get what we call the "back-side bus." There was a front-side bus, which was the memory interface. There was also a back-side bus on the cartridge which had some high speed SRAM on it. Robinson: That was all that Slot 1 stuff? Steve Nugent: Yes, it was the first slot 1 processor. That was my baby. Robinson: Sixteen years is a long time to be at Intel, actually. I have had friends that say, "If you last 16 years with Intel, you are either doing something right, or something wrong." Which was it? Steve Nugent: Myself, I took a lot of training at Intel to actually be able to cope. There are very strong personalities there. I am a type-A personality myself. I think that when I began at Intel; my communication skills were not the best. I took a lot of courses there that really benefited me. It made me a better listener. Janet still helps me out a lot in that area. Janet Nugent: He really grew a lot once he became a manager. He really started to recognize that other people had strengths, and he let them develop their strengths. He let them have certain pieces of the project. Robinson: I have a very good friend who spent a brief time at Intel and he came away from there just shaking his head saying that it was the most Darwinian experience he had ever had in his life. Janet Nugent: It is a pressure cooker.

A pair of Parasound JC-1's are driven by custom-modified Sony DVD player; the Mark Levinson is also tweaked—all mods done by Empirical Audio Steve Nugent: The culture creates a lot of tension, because you are always rated against other people, not on the basis of your own performance. There is no such thing as an absolute performance at Intel; it is always relative to someone else. If you are in a group of very high achievers, it can be very difficult to get a good rating even though you are very successful in what you are doing. That can be very difficult. Janet Nugent: Most of the people there are very productive and very successful. Steve Nugent: Yeah, you don't even get hired at Intel unless you are really good. Janet Nugent: It is kind of like being rated against the very best all of the time. Robinson: So—how in the heck do you go from this kind of a background and mega-corporation culture and decide to go into fine audio? Steve Nugent: I think it is more of a matter of the fact that I have always wanted to work for myself. When I was to the point where financially I could swing that, I have always wanted to do it. I think a lot of engineers that I worked with at Intel have the same feeling. They all want to work for themselves in some capacity or other. It is difficult. My entire family—my dad, my brother who is an engineer, a metallurgical engineer who is actually helpful—we all had a really difficult time knuckling under to the corporate culture. You have to really do unpleasant things, especially early on in the career. You have to take a lot of grunt jobs, not complain, and just do it. My brother and my dad broke away much earlier and did their own thing with their own businesses. My dad had his own business for most of his career, a building business. I tried to hang in there long enough so that financially I could afford to go off and do this business and not have to build the business quickly. One of the criteria that I laid down for myself was that I didn't want to have to build a business quickly. The typical American way of doing business is that you go as quickly as possible. You get funding from whatever source you can, and you try to make a big splash in the market, etc. You try and get into high volume as quickly as possible to bring cost down. All of those things I have actually avoided. I have taken the opposite tack in all of this. I want to do this because I am passionate about music and I feel I am talented at electronics. I don't really want to go into business overnight. I don't necessarily want this to become huge. I would just like to have a satisfying business that I can run for myself. Robinson: How long have you guys been at this now? When did you first found Empirical Audio? Steve Nugent: It was founded in 1994. Janet Nugent: We haven't been in the public eye as much. Steve Nugent: The first 5-6 years was strictly doing experiments, simulations, and filing for patents. We've got four patents now, and a fifth in the oven. It should be issued fairly soon. Four cable patents and one connector patent.

A few of Steve Nugent's patents… Robinson: What kind of patent work in general? How would you summarize your patents? Steve Nugent: It was really fortunate for me that I did so many patents at Intel. I became so familiar with the process, the verbiage and the structure of patents. I could write them myself. Early on, I didn't have to pay a patent attorney or patent agent to write these patents for me. I wrote most of these patents myself. Now that I have a little bit more financial help, I can actually pay the patent attorney to at least do some of the work and finalize the claims. Most of the patents are centered on a couple of aspects. The first one is that we try to do bare wire, what we call "bare wire technology," wherever possible in the speaker cables, interconnects and power cables. That means uninsulated wire. Ideally, what I have always tried to do is attempt to create inventions that allow us to suspend bare wires in free space. It turns out that this is exactly what you need for interconnects: bare wires in free space. That is my theory; I think I am correct on that account.

…and here are the rest of ‘em! Steve and Janet in the "hall of patents." On the speaker cables, it is obviously more difficult because they are two different situations. They are physically different. In the case of interconnects, low capacitance is what you are after. In the case of power cables and speaker cables, it is low inductance and low resistance that you are after. That is based on lots of simulation work. Robinson: When you talk about simulations and modeling, how did you do that? Steve Nugent: At first, I had some concepts of structures that I wanted to play with for speaker cables. I also had some zip cord and large zip cord that I used for some years. I knew how that sounded. I knew how this other experimental cable sounded. I knew the differences there. Robinson: You are telling me that "cables ain't cables." Steve Nugent: They sounded different from each other. What I did was that I created a model that I could bring into SPICE, which is a simulation tool. It is a Simulation Program for Integrated Circuit Electronics. SPICE is the industry workhorse tool that is used for analog simulation. There are several versions of spice out there. There are P-SPICE, H-SPICE. Between Intel and my own home system, I had access to a number of different SPICE tools. I was able to build models for not only the zip cord but for several of my own structures that I wanted to play with. I was able to run simulations using SPICE once I had those models. That is the key thing, how to build a model that is both accurate and correlated. You build a model, quite simply, with a circuit diagram. You can build a model of a cable this way, but it will be lacking a lot of the field interactions. It won't really reflect Maxwell's field equations unless you have used a more complicated solver. That was what I did. I used a field solver called Ansoft Maxwell. Maxwell is quite a good field solver. The way you input your models into that is you describe it physically. You can do a cross section or you can do a 3-D model. You describe the materials, the geometries, the spacings and then you just say "go!" and it spits out a model that you can plug into a SPICE simulation. You can then bring it into a system. That is the whole purpose of the SPICE simulation: to do the full system end to end. You've got a model for the speaker, you've got a model for the driver—whether it is a power amplifier or a pre-amp—and then you've got your wire, which is all the rest. Hopefully you've got a good model for that. What I mean by "correlation" is to actually go on the bench and reproduce what we have in simulation on the bench as closely as you can. Then look at the two waveforms and ask yourself the question, "Do they match?"

Robinson: When you talk about correlation of model to your prototyping, did you find at first that there was divergence, or did you find it was closely parallel? Steve Nugent: Some of the things that I was trying to model—for instance ferrite beads—very difficult to build a model that matched. As far as just wire models and dielectrics and spacings and all, the Ansoft Maxwell solver was very close. If you look at the website, there is some correlation data out there for the zip cord. It is pretty much dead-on. I put a step response through a piece of zip cord and look at it on the o-scope. The rise-time, ringing and overshoots are almost identical. Robinson: You know that you will have to realize that you are going to disappoint a lot of buddies over at AES when you say things like that. There are still a lot of folks who believe that zip cord is just fine. That is not what you are finding, I take it? Steve Nugent: If you ascribe to the theory that human hearing stops dead at 20 kilohertz and that any kind of phase shift at 10-20 kilohertz is not audible anyway, then I would agree that it is probable that between zip cord and the other stuff you will not hear a difference. My theory is that human ears actually hear much better than that. That you hear well beyond and that, and that phase differences do matter. Those are the kind of things that my cables attack. The simulations clearly show that the phase shift is much, much higher with a zip cord than with a low inductance cable with the right kind of field coupling in it. Robinson: Let's talk about design philosophy for a moment. What is it that you guys at Empirical are seeking to do? What is your design philosophy in short?

Steve Nugent: What we want to do is create a cable that sounds like no cable at all. It sounds like you actually butt the two components right up to each other. We want something that is absolutely neutral and doesn't store energy, because cables that store energy have to release it. If you use air dielectrics, the energy storage is extremely small and the release is instantaneous pretty much. That is what we are after. Robinson: I am chuckling because it reminds me of what my good friend George Cardas said years ago. Somebody was talking to him about cable when we were down visiting him in at his listening room in Bandon. They asked him the same question: "What is the best cable?" George laughed and said, "The best cable is no cable." Steve Nugent: It's funny because some audiophiles claim that you have to have some cable in the system or it doesn't sound right. I don't agree. If the drivers and the receivers of on the components are designed right, you should be able to butt them right up against each other. If you design a good cable and put it in between the components, it should sound the same. There should be no difference, really. Janet Nugent: I think that our experience has been that when we use our cables, it allows us to hear what has been recorded. What the actual instrument is. We have had experiences where we have gone to people's houses and—I remember one instance where the playback sounded like drum sticks were tapping against each other. When we removed that cable and put our cable in, we found out that it was a cow bell! There is a huge difference between those two sounds. We want to hear what has been recorded. Robinson: It is like being able to distinguish an oboe from a bassoon. I have heard systems where you sit there and listen and you can't quite place which instrument you are hearing at that point. The further I have gone into fine audio, the more disconcerting I find that. If I listen to a system and it does not have the ability to resolve, if it doesn't have that a real degree of fidelity then we are in trouble right there. Either I don't know what I am listening for, or the system isn't telling me what I need to know. That is on an analytical level. There is an emotional level to music too. I am curious about that. What do you see as the role of emotion in the work that you are doing? Steve Nugent: In my personal experience, that is paramount. If the music is not uplifting, then I am not going to bother to listen. It has to be an emotional experience for me. I am an emotional person.

Janet Nugent: I know one night we were sitting on the couch and playing music. He said that it "brings me so much joy." That is the emotion that I think we are trying to deliver to other people. Some joy and exhilaration! Those would be the two. Steve Nugent: I agree. That is what makes it all worthwhile. It is not, "can I hear this better than that?" It is not sitting there being critical of the music and saying "is this better than that?" Instead I ask, "When I listen, do I feel better? Do I feel uplifted? Is it a revelation?" That is what I am after. Robinson: What is the relationship between the computer models you run on SPICE and listening? Steve Nugent: The first step, obviously, is to get something close. That is what I attempt to do with both experimental and modeling work is to get close. After that, the fine tuning is ultimately manual and labor-intensive, and involves a lot of listening. You can't leave that out. It is like voicing a violin. You've got to do that part. It is like voicing a speaker. Janet Nugent: We are part of the system. I was going to say that Steve really does two things: one is that he is an architect of systems, so he knows that the wires are part of the system and he is trying to give something exceptional to that part. The other is that he is an inventor. He will continue going down that path in trying to get "the ultimate." Steve Nugent: My hero is actually Nicola Tesla! Robinson: What is your view of the current status of measurements like conductance, capacitance, resistance, and what we are hearing? There are a lot of fine audio wire companies out there. There is constant and even chronic argument and debate on measurements vs. listening. Where do you see this stacking up right now, Steve?

Steve Nugent: My opinion and my philosophy are that there are first-order parametrics. Those have to be tackled first. I think what is happening is that a lot of cable companies attack only the parametrics, the L, C and the R. A few of them attack dielectric absorption. Other companies attack the metallurgy. I don't see very many attacking both. In fact, I see companies actually saying, "It is not about L, C and R." That is simply not true. When I hear them say that, I've got to believe there is something missing in the technical background. It is obvious when you do the simulations that you have got to get L, C and R right first. But, the metallurgy is just as important, if not more important. Over the last year or so, we have just become really sensitive to the metallurgy issue. Prior to that, all the patents were focused on the parametrics and trying to get L, C and R right. We discovered that when we optimized those to the max possible within our price-point constraints, it still wasn't good enough. There was still something missing. The metallurgy was the missing piece. Now that we have that, we are pretty confident of our products. We are really happy with the way they sound. The other thing that is interesting too, is that I have noticed a lot of companies—notably less technical companies than ours—will apply the same design to both interconnects and speaker cables. That just dumbfounds me when that happens. I just don't understand that at all. Robinson: What is the difference between the two as far as you are concerned? Steve Nugent: The environment of an interconnect—most people say, "Well, it is a delicate, small signal." It has nothing to do with that. It really has to do with the output impedance of the driver of that system and the input impedance of the receiver. Everything about it is that. When you take that into account and you do a sweep—what I mean by a sweep is that you might hold L steady and sweep low C to high C, and see what effect that has. You might hold C steady at some value and sweep L. See what effect it has. You will find immediately that C is the dominant parametric. It is the dominant parameter. L and R are really almost unimportant. When you do the same test with a speaker cable or a power cable, again, it is a different environment now. It is a very low output impedance and generally a low input impedance. Things like cross-talk and noise pick-up are really third order, fourth order, if an issue at all. In those cases, it is the inductances that become the first order effect. It just takes a couple of SPICE simulations and you go, "Oh, well. This is obvious." Another thing that people are often concerned about is impedance "matching." That is a difficult thing to do in an audio system because none of it is designed to be matched. Secondly, a lot of the parameters like the input impedance—if you are talking interconnect—the input impedance is really a "don't care" unless it is extremely low. It doesn't really matter if it is a 1K, 10K or a 100K. The output impedance is really the important parameter. Robinson: The world of the pre-amp output is more important? Steve Nugent: Yes. Pre-amp output is much more important than a power amp input impedance. Robinson: Of course, much of the problem is that we do have a lot of companies who build one side or the other, but not both. On the other hand, we have companies like Linn or Audio Research who build both ends, so you can be reasonably sure that if you buy those two pieces they will be talking to each other pretty well. At Positive Feedback we have stressed system synergy for many years. I have had some rather well-known names in audio on the journalistic side who have taken serious issue with us on this question. I had a phone conversation years ago with one very well-known editor, who shall remain nameless—but you know who you are!—told me flat-out that Positive Feedback was nuts, and that our emphasis on system synergy was nonsense. "A device under test is a device under test," and with a true reference system you should be able to just drop a component in and see how it sounds because it is a reference system. You will know how it sounds. My response was a variation of, "You've got to be kidding me." You drop a component in and everything changes—especially if it has not been matched. We seem to have some people who think little of dropping a piece in regardless of those parameters or synergy, and just assuming that things "work." From their perspective, if the component doesn't sound good when dropped in, the problem is what you substituted and not the synergy—or lack of same. To your mind, does that tell you that in fine audio we may have some problems with a lack of technical expertise, of people not understanding some basic issues?

Steve Nugent: There has certainly always been a vacuum when it comes to standards. It is really difficult to mix and match, because there is such a wide variation. Speaker-amplifier synergy is probably the number one problem that the audiophile is up against. It runs the full gamut of speakers whose impedance is wildly changing over frequency, to speakers that are extremely low impedance to fairly high impedance. Matching an amplifier to that can be a challenge. It is probably THE challenge. That, I think, is one of the difficulties of being a cable manufacturer. You really don't know if that synergy has been reached with your customer. When he plugs your cable in, has he got these other things already figured out? Are they dialed in or not? Often, that is not the case. I had an epiphany here recently myself. We have recently gotten some new mono-blocks, some Parasound JC-1's, and I had been really interested in eliminating a preamp and using passive line-stage. I discovered that this particular amplifier, which is an outstanding amplifier, really seemed to lose a lot of dynamics when I used a passive line stage. Even though the input impedance was some 50K Ohms, it shouldn't make a difference — but it definitely did. It needed every micro-amp of current that you wanted to send it. If you didn't give it those micro-amps, if you put a resistor in the way, it lost dynamic range. It lost slam. It was a real eye-opener. Now I am convinced that synergy is really important: speaker to amplifier, and preamp to amp. I am not so convinced that there is really synergy from your source to your pre. I think that is probably the one area where, most of the time, you put a low capacitance, low dielectric absorption cable in there, and it will sound good no matter what. No matter if it is a tube output stage or transistor output stage. That was an eye-opener for me. That is the one thing, besides having such a large variation in source components—some good, some bad—the customer doesn't know whether he has something good or bad, because it is a whole system thing. Is it my speakers? Is it my amp? Is it my preamp? Robinson: There is no data base. There is no place that you can go, let's say on the web, and at least see categories. These represent high vs. low impedance. Why don't we see if I mix this with that—is that generally good or generally a bad idea? Steve Nugent: Here is an example that would lead you down the garden path. I had a Coda amplifier, which is a very nice, sweet sounding amplifier. I put a passive line stage on that and it didn't change the character of the sound one bit—which wasn't the case with the Parasound JC-1's. It would lead you to believe that a passive line stage could be used on any system. It is simply not true. Robinson: I have seen so much variation over the years as I have listened to various combinations of gear. I have to come to the conclusion that a lot of folks are not aware of these issues. They really do assume that the manufacturers do things "right," and you just assume it should work. They may connect gear and they may blame cable, speakers, a source. The blame-placing shifts the issue all over the place. Steve Nugent: The usual effect is "I need a cable to be used as a tone control." Robinson: "I read about this recommended component that is class-A. I bought one and dropped it in and all of the sudden, things sound terrible. What is going on?!" That sort of thing. Steve Nugent: It is a system thing. It takes a lot of tweaking, time and actually knowledge to be able to find what is going wrong and fix it. Robinson: How would you say your cables contribute to people having good experiences with music? What is your cables' part? Steve Nugent: I think there are a couple of words that describe what our cables do. One is detail. We feel that the detail we deliver is really unparalleled. You will hear things that you have never heard before in the music. That was an artifact of the work we did on the parametrics, bringing L, C and R work and dielectric absorption and getting that down really low. The other aspect of it is eliminating sibilance. Detail without sibilance. That is what makes listening to music a religious experience. Unless you hear all of the percussion completely clean and clear and without sibilance, you are not getting the music delivered. Robinson: Do you find that your cables generally match pretty well with all kinds of components, or are there some types of gear that it is better with? Steve Nugent: I think we have found pretty much everything works with our cables. Any system that we have put our cables into, there was an improvement. Janet Nugent: I would say that. Steve Nugent: Occasionally, we get a system where there might be a harsh sounding CD player. The cables that were in there before were "tone control cables." Now we put our cables in which are not tone control cables, and that harshness does come through. Sometimes the customer is thinking that it is our cables that are at fault and not his CD player. We do get that. Sometimes they get sent back for that reason. Janet Nugent: We get very few returns. Steve Nugent: Very few. We try to work with the customer to develop a system view, and to try and point out, "Well, this component may be problematic. You might consider borrowing another one from a friend and then try our cables, because you may not like the sound of that component." Janet Nugent: We typically ask them what is in their system. Steve Nugent: A lot of other cable companies talk about the fact that their cables uncover any weak links in the system, and that they are going to expose them. I guess that is the case with our cables. It is going to expose anything that is a weak link. Robinson: You guys had your baptism with fire with SACD recently. Clearly, high resolution digital is going to push the envelope for this. You want to talk about things happening above 20,000 cycles and proper phase and harmonic structure all the way out into the ultrasonic range, and the effect it has on the sonic range, SACD is certainly where it is going to show. What sort of challenges do you see high resolution digital making for your company? Steve Nugent: I don't really see it as a challenge. I think that what we have delivered so far, and what we will continue to deliver, are cables that perform in the megahertz range. Flat-out to Megahertz, and phase shifts that are extremely small. I think it dovetails nicely into SACD. Robinson: This actually sounds like some of your Intel background talking! It is the same thing I hear from Jennifer Crock over at JENA Labs when she talks on the subject. "Well of course. We want high bandwidth, way off into the x-ray range. We want the ability to deliver what is there, regardless." It was the old assumption that audio was only 20 Hz-20 KHz that was killing us. I have heard some cables that definitely sound like tone controls. There are some cable designers out there for whom this is the direction they wish to go. Steve Nugent: I think customers often confuse the elimination of sibilance by using a tone control cable as opposed to the elimination of sibilance when you've got a good design. There is a big difference there. When you've got "tone control cable," you eliminate sibilance—but you also eliminate music! Robinson: In our last conversation, that was one of my concerns. I told you about people whose systems have drifted into a given sound that they may find pleasant, but which may or may not reflect what was going on in the recording. ("Audiophiles in the land of the Lotus Eaters" and all that.) You could get off into a digression on fidelity and accuracy—which I personally think that DSD and SACD are actually reintroducing as a valid topic of discussion. Now we can go back to starting to talk once more about fidelity, about resolution. Ultimately, if we are doing things right, there ought to be no dichotomy between accuracy and musicality. For so many years, there was the Devil's choice of "Well, do we want ‘musical,' or do we want it to be accurate?" My response has been that it should not be an "either/or" question. "Accuracy" can only be defined if you have a known standard for a source. A lot of people who speak about accuracy really don't know what they are talking about. They haven't heard the source. They have no idea what it is like to be in a studio, or to listen to the inputs at the console. They have no idea what was experienced in there, or what the art of audio engineering is all about. They say simply, "This sounds accurate. This is accurate." Others say, "Yuck! What an ugly recording. Give me musical recordings." In the audio arts, what happens in the studio in that recording process, and the choices that are made artistically, should result in recording in which "accuracy" and "musicality" do not diverge. Assuming that we are crafting fine recordings in the first place (not always true!), an "accurate" playback will be "musical." And that is what should be delivered at the other end. That does get us to source material issues. I do think that with the best of the current turntables and LPs, and with the best of current SACD systems and the best of DSD, we are truly closing in on delivering the studio to the listening room. I think that we are merging accuracy and musicality again. That is where work like yours is going to be important, Steve. Because, in between all of those component points in an audio system, there are the pathways — the power cables, interconnects and speaker cables. Steve Nugent: I agree. What I have tended to do over time, when I do my critical listening to "voice a cable," whether I am deciding to go smaller or larger for the gauge of the wire, or whether I decide that shielding of this cable is a bad idea—those kinds of things—more often than not, I will use non-music recordings. I will use water. I will use tinkling glass. Birds. Robinson: Mike Pappas talks about "Tibetan Yak music," but we will leave that behind…. Steve Nugent: There is a set of recordings out there that are fairly easy to come by that have non-music material. You know what running water sounds like. You know what a paddle from a canoe in water sounds like. Robinson: When you actually voice your cables then, you prefer to use what some people would call "sound effects." Steve Nugent: Yes. I use a lot of sound effects to voice my cables. That's because music recordings can be misleading. You don't know how it was processed or recorded. In fact, if I do use music, I tend to use stuff from the 60's or late 50's that was minimalistically miked and had very little processing done to it. Robinson: I notice that for audio reproduction you have been using CD up to this point in time; you don't have a turn table on your system. Are you looking at trying out one of the higher resolution technologies? Robinson: It is difficult. There is a lot going on. One of the things that I find interesting is how many audiophiles have to re-work their systems in light of SACD. It is forcing a re-making of the whole chain. It is a system approach that you talked about. Once something changes that massively at the signal end, well, now we have to look at everything else downstream. Steve Nugent: What I am concerned about is the recording chain. We have been trying to break into the recording studio because that is sort of our last frontier, I think. It is unfortunate that this would be true. You would think they would be the first to adopt really low loss cables and interconnects and balanced cables that really deliver the full musical experience with no phase shift and no dielectric absorption. It is not true. They are very cost-sensitive. In most mixing consoles there are hundreds of balanced connections, so it is a pretty expensive proposition. What we have tried to do to get our foot in the door there, is to hook up with live recording engineers. There you are talking about someone that uses very few cables, a few mike cables, a couple of cables from the mixing console to the recording machines. That is a lot lower investment to go after. We are in the process right now of having some CDs made using our cables in the recording chain for live music reproduction. We are really excited about that. If we are successful in that, we hope to have on the same CD "standard cables" versus our cables, and see what the difference in sound is going to be. Robinson: You are relocating your operations from the Portland area out to Bend, Oregon. Now that you are heading out to the high desert country, what is the future of your company? Steve Nugent: The interesting thing is that actually Sisters and Janet Nugent: It is developing! Steve Nugent: The Folk festival, the Jazz festival. It is attracting a lot of high power players now. There are some musical teaching venues, schools and organizations sprouting up that are really useful. A lot of musicians are around in the Eugene area and Bend. Good musicians. Prairie Home Companion is coming to Bend. The Beach Boys. There is more and more of this going to happen. There are a couple of smaller recording studios in Sisters, and one in Bend. We are going to be interested in working with those people. We would like to try to pull together some kind of Central Oregon Audio Society. What we would like to do is try to benefit those people, but also try to benefit the community by generating some funds that can be used to help support those events, sponsor those events. Robinson: So in the future, you are going to cut loose and pursue the things that you love. Where can people get in touch with you? What is going to be the new address, the new phone number, the website? Steve Nugent: As soon as we move which will be in the next few days, we will post the new address out on the website. Robinson: What is the website for the readers? Steve Nugent: The website is at http://www.empiricalaudio.com.

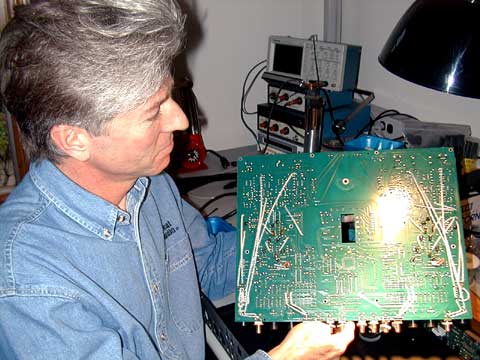

There is one other thing that I wanted to mention, too. That was the modding business. We are starting to do audio modifications. Right now, it is a word of mouth thing over the web. We don't advertise anything on the web page about mods yet. It is something that Dan Wright got me interested in. Dan traded me some cables for one of his modded Perpetual Technologies DACs. Robinson: Aha! Dan has corrupted you! Steve Nugent: I got a feel for what Dan is doing. I started tinkering myself. I realized, after opening some of the boxes that I own, notably a Mark Levinson 38, that there was a lot that I could do to improve the circuit. In fact, almost everything from the digital front end to the power amps to the speakers, I can go in there, mod them and improve them. I am really excited about that prospect of doing a little bit of audio modding. Robinson: One of the things that I remember about your mods that was really different is that you actually work at the printed circuit board level. You work with traces and circuit leads on the board itself. Steve Nugent: Yeah, it turns out that analog circuits are a little bit easier to reverse engineer than digital circuits. It is fairly easy to draw the picture—here it is, here is what they did, and look at it and say, "This doesn't make sense. This component ought to go here not there. By the way, they ran a 12.5 inch trace on the board and that was a really silly thing to do; cut that sucker right out and rewire it externally." It is an opportunity to use some of what we call perfect crystal silver in the signal path. After making a few of those changes, it really seems to make a big difference. I am excited! There are a lot of other design decisions that are commonly and routinely made by designers that do mass-produced consumer gear, because it has to be machine assembled. Even stuff that is hand assembled, a lot of it is designed for ease of assembly. When you do that, traces end up being longer than they need to be. Op-amps have lower bandwidth than they really should have, than the specs say they should have. There is more noise introduced. Robinson: A penny here and a penny there. Savings! Steve Nugent: It's those kinds of things that if you are willing to put up with a little kludge on the circuit board, the improvements are quite astounding. Robinson: It is really amazing, even with some of the stellar kinds of designs that normally on the class-A lists, you go inside and there are some surprising things going on inside some components. Places where clearly even the manufacturer was kludging some of the stuff. You can see of these last minute rewire jobs, and the "We've got to be ready for CES!" stuff. Steve Nugent: The reality is that an analog engineer, if he is really good, will probably not be designing consumer electronics gear for a small company. You are more likely finding him working for Intel and getting big stock options. As a result, finding an analog designer that knows power delivery, grounding, shielding and good analog design—and combining all of those together with a little bit about transmission lines—who knows the whole thing from top to bottom right is a fairly rare person. Robinson: As far as the profession goes, most of your EE's are not going into audio. They are heading out into computer technology because that is where the money is, and they will be well paid. Audio as a profession is viewed as that embarrassing kid brother over there. Most electrical engineers figure that anybody who ends up in audio is kind of washed up. It is a mark of how things have changed in audio. There was a time that audio was quite a place to be. If you were in audio electronics it was very cool back in the 50's and 60's, but not so much now. Steve Nugent: In fact, a lot of analog engineers are being sucked up into RF and wireless networking. Cell phones. There is a lot of analog required in that. Robinson: There is a lot of money in that. Janet Nugent: Did you want to talk about what our future ideas and plans are for our wire? Robinson: That would be good. Janet Nugent: Working with a company in France.

Steve Nugent: We have some things in the oven right now that are looking very promising. As opposed to doing mods for individual customers and trying to improve their components, we are actually getting in bed with a few tube amplifier manufacturers to begin with. We are looking at rewiring and doing some topology changes inside their amplifiers to improve them. We would like to get our silver wire in there. Not just get the silver wire. I am in there mucking with the circuit board. Even with point to point wiring, I think there are things that I can do to improve the guts—and that means the topologies—of the wiring. That means power delivery, signal paths and isolating and improving noise figure. Robinson: There are only a few people who do point to point anymore. So much of it is circuit board, even if it is tubed. I am sure there is a lot of room for improvement in the future. You have got several companies you are working with now? You see it as a major direction for you guys in the future? Steve Nugent: We are really looking at it as more of a brand name recognition sort of thing. We will just teach the manufacturers how to do the mods. We will sell them some wire and some subassemblies. Our logo will be on their chassis: Wired with Empirical Audio. Robinson: I wish you very well; we have a native interest in people in the Pacific Northwest in the audio arts. It is always a great thing. Thank you, Steve and Janet. |