|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 54

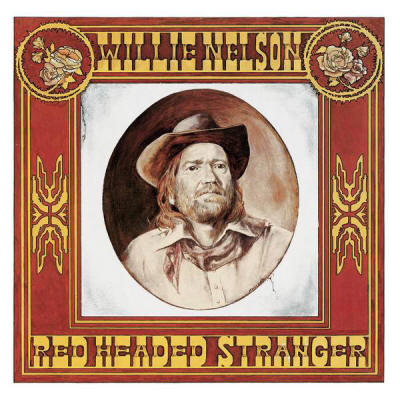

Willie Nelson, Red Headed Stranger,

Impex 180-gram LP

Forget Stardust. It was a bold move for a country artist to record a set of Great American Songbook standards—especially a singer with such a non-standard voice—yet, as we all know, the experiment succeeded, and the record sold very well. It was also well recorded, and has been audiophile fare since its release in 1978. Nevertheless, it remains an anomaly in the Willie Nelson catalog, and I know I am not alone in finding it very much hit-or-miss. Not so Red Headed Stranger, released three years before Stardust. Red Headed Stranger may or may not be the quintessential Willie Nelson record, but it is without question the record that defined his style, and it is the record that put him on the map. Willie Nelson had been on the borders of the map for quite some time before he made Red Headed Stranger, known as a songwriter and musician before becoming known as a singer. His early hits were written for other people, notably "Night Life" for Ray Price and "Crazy" for Patsy Cline, and these songs still pay residuals a half a century after they were written. Writing hit songs impressed the Nashville producers, and by the early 1960s, Nelson was singing on his own records. On his 60s LPs, most of them recorded for RCA and produced by Chet Atkins, the Willie Nelson we've come to know is recognizable, but the Nashville arrangements of these records, with their crooning backup singers, tinkling pianos, and other excrescences, did not suit his nasal voice and quirky phrasing. The records sold, but not particularly well, and by the early 1970s, Nelson had left Nashville, moved back to Texas, and retired from the record business. His retirement didn't last long. By 1973 he had signed with Atlantic Records and produced two albums, Shotgun Willie and Phases And Stages, that represented a departure both for Willie Nelson and for country music. The sound of these records was more honky-tonk than countrypolitan. The kitschy pop trimmings were gone. Solo violins replaced entire string sections. Nelson's acoustic guitar was now given nearly as much prominence as his voice. The songs also addressed the audience in a much more direct fashion, and were more openly emotional. Phases And Stages should have been the breakthrough record, but even though it wasn't a hit, it remains one of the most original country albums ever made. There had been a few records that collected songs around a theme (including the fantastic Night Life album that Ray Price built around Willie Nelson's song), but Phases And Stages was a full-blown concept album, tightly constructed to tell the story of a dissolving marriage, first from the perspective of the wife, then from the perspective of the husband. The record opens with a brief statement of the "Phases And Stages" theme, which reappears throughout the album as a transitional device. In the first scene, we observe the disgruntled wife doing housework, then follow the progress of her decision to leave her husband, as she returns to her mother's house, goes to a honky-tonk to forget her troubles, and wonders how she will know if she falls in love again. On side two, we find the husband literally taking off from the scene (in an airplane), ordering a drink despite it being first thing in the morning, and recalling the day he came home to find his wife had left him. The rest of his journey is more emotional than physical, as he moves through disbelief, sorrow, confusion, and finally resignation. Red Headed Stranger was Nelson's first album for Columbia after moving on from Atlantic. Though it is also a concept album, it is much more loosely structured than Phases And Stages. Part of the reason for this is that—unlike the previous record, which he wrote in its entirety—many of the songs on the album are not Willie Nelson's. This is not a shortcoming, but is in fact one of the record's most interesting features. The narrative framework is created by Nelson's compositions, several of which appear and reappear in fragmentary form, interspersed with songs by other writers, which, because they address the classic themes of country music—love, deceit, loss, loneliness—carry the story forward, though only by implication. The story begins with "Time Of The Preacher," a Nelson tune about a man who, in "the year of '01," is abandoned by his wife for one of her previous lovers, and whose anguish is so great that he loses his mind. When the song ends (or seems to), it is followed by the Eddy Arnold/Wally Fowler tune "I Couldn't Believe It Was True," which sustains the theme. "Time Of The Preacher" is then reprised with an extra verse, which tells us that "the killing has begun." In the next song, also Nelson's, the man discovers his wife and her lover in a tavern and kills them. The "Red Headed Stranger" theme then appears for the first time, but is interrupted by the song that became Willie Nelson's first number-one hit on the country charts—Fred Roses' "Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain," first recorded in 1945 by Roy Acuff in a version that falls far short of Willie's in the depth of its pathos. When the "Stranger" theme then reappears, Nelson adds details to the story. We hear of the red headed stranger's arrival in an unspecified location, riding a black stallion and towing the bay horse that had belonged to his wife. When an unnamed yellow-haired lady "casts eyes on the bay" and dares to touch it, the stranger abruptly shoots and kills her. In the Wild West, which still existed in parts of this country in "the year of '01," he is found innocent of any crime, since the woman was clearly trying to steal his horse. As the stranger rides on, the "Time Of The Preacher" theme is briefly reprised, and the first side of the record ends with an instrumental passage composed by Nelson. On the second side of the record, the narrative is all but dropped. The recurring musical themes fail to appear, and the stranger is not even mentioned. Nevertheless, the narrative of the first half of the album is a constant presence in the background of the second, and it colors the events and themes that appear in each of the songs. The first—the only one written by Nelson aside from the closing instrumental—is very brief, yet contains a strong suggestion that it is furthering the narrative. An unidentified man meets an unidentified woman at a tavern, and they smile and begin to dance. Dance music follows, then a beautiful version of Hank Cochran's "Can I Sleep In Your Arms?" The implication is that the man is the red headed stranger, and that he has found at least some comfort in the company of this woman, yet this is far from clearly stated. As the album draws to a close, Nelson sings "Remember Me," an obscure tune by Scotty Wiseman (author of the much less obscure "Have I Told You Lately That I Love You?"), a song addressed to one former lover by another. It is not clear who is being addressed and who is doing the addressing, though again the implication is that the red headed stranger is the narrator, and that any comfort he found was merely temporary. Still, in the next song, Bill Callery's "Hands On The Wheel," the narrator claims to have found himself in the eyes of his lover—suggesting, at last, that the possibility is always there. Another extraordinary thing about Red Headed Stranger is the way it was recorded. The arrangements are extremely spare, almost stark. Much of the time, we hear only Willie Nelson's voice and his guitar. Other instruments—piano, accordion, banjo, harmonica, tambourine, a second guitar—appear from time to time, though rarely for more than a few moments. Occasionally a minimal rhythm section (bass and drums) kicks in. The musical framework of the album is so minimal that apparently the Columbia record executives nearly rejected it because they thought it was a demo recording. It's hard to blame the record execs, as they were hearing what had to be the most un-"produced" country record ever made. By stripping away the gingerbread that usually adorned country records, Willie Nelson had created something almost stunning in its intimacy. The indirect nature of the album's storytelling is counterbalanced by the directness of the recording, which puts Willie Nelson and his guitar directly in front of you and the other instruments just a short distance behind. There was much a stake for Willie Nelson at this stage of his career. He took a considerable risk in making this record, in terms of both its formal and sonic presentation, and it paid off. While the original LP sounds very good, it is pressed on typically flimsy 70s vinyl, and sounds a little bit thin, especially when compared to the Impex pressing, which fleshes out the sound of the recording very nicely. It also has better resolution—the sound of Willie's voice bouncing off the walls of the studio is more clearly heard, as are the little details of his guitar playing, among other niceties. The you-are-thereness of the album (or the he-is-hereness, depending upon how you look at it), is therefore increased, but a more important difference is that the emotional content of the record has been taken up a notch or two. Keep a hankie handy for "Blue Eyes Crying In The Rain." If you have even the slightest interest in country music, this is essential. Even if you hate country music (at least in the form of the egregious garbage the genre has become), give it a try. Dan Meinwald is the importer for E.A.R., Marten, Townshend, and Jorma Design

|