|

You are reading the older HTML site Positive Feedback ISSUE 46november/december 2009

The Tape Project Reissue Series - Reel-to-Reel Tape:

The Real High Resolution Format

Why would any sane audiophile—especially in the age of digital—add a state-of-the-art, reel-to-reel based, analog front-end to their high-end audio system? A lifeline isn't necessary to answer the aforementioned question: sound quality. Reel-to-reel master tapes and the newly released Tape Project 15-ips, 2-track super audiophile releases are the real deal—the real high resolution recording and playback format. Now once upon a time—long before digital, music servers, MP3 or even more hideous formats—reel-to-reel tapes decks were THE source medium of choice for both audiophiles and high-end audio manufacturers. Reel-to-reel tape machines were once a common sight at high-end audio shows. And for good reason. Those 15-ips, 2-track master tapes could make a silk purse out of the proverbial sow's ear. Even a pair of JBL speakers sounded like world beaters when the source material was a master tape. There was simply more information on the tape that gave the music a denser sense of harmonic structure missing with the LP. The tapes sounded far less mechanical and possessed a sense of ease and unrestricted dynamics, particularly in the low frequencies, that eluded turntables past (and even some present). Instruments were fleshed out with an extraordinary sense of space surrounding the musicians and orchestra unmatched by the commercial LP release. As Mike Spitz of ATR Services says, "Nothing sounds like tape!" Reel-to-reel tape machines and accompanying software also didn't escape the attention of the days leading high-end audio magazines either. Both leading high-end audio publications of the day, Stereophile, with J. Gordon Holt at the helm and The Absolute Sound, guided by Harry Pearson (and ably assisted by Patrick H. Donleycott on reel-to-reel reviews), featured regular reviews of consumer reel-to-reel tape decks and pre-recorded commercially released software. In addition, JGH wrote regular columns dealing with the ins and outs of making home recordings—something sadly lost today. And back in those days, the best reel-to-reel decks and 7½-ips, 2-track tapes were superior to most analog turntables; As Harry Pearson recalled in a recent email, "In a word though, we stopped reviewing reel-to-reel decks when reel-to-reel tapes were discontinued. and they were, in the early days of the stereo disc, infinitely superior to vinyl (except at the top end and except for the often pre-Dolby tape hiss days). But all good things must come to an end. The ability to produce LPs in mass quantities coupled with their convenience and lower prices spelled the end for reel-to-reel tapes and machines. Reel-to-reel tapes machines became, with the exception of a few hardcore audiophiles, the province of studio engineers. The Reincarnation of Reel-to-Reel Tapes, or Reel Music in the Round!

The following is a chronicle of my nine month (and still continuing) quest for the high-end audio Holy Grail. Now, I've been tempted more than once in the thirty plus years of involvement in high-end audio, to invest in a reel-to-reel tape deck. Two issues, however, always stopped me from taking the Nestea plunge. The first concern was having enough experience to gauge the shape of the tape deck, and more specifically, the tape heads. Next, and perhaps the overriding factor, was the availability of high quality software; today's state-of-art turntables surpass the sound quality of most commercially recorded 2- and 4-track 7½-ips tapes. (Of course these comparisons have to somewhat tempered since one doesn't know if the tapes and LPs were made, and that's often not the case, from the same sources.) But then a year or so ago while wasting time surfing the net, I happened upon the ultimate audiophile's dream otherwise known as The Tape Project (www.tapeproject.com). What more could any audiophile ask for? Master tape-like sound on their own reference systems! In fact, The Tape Project reel-to-reel tape releases are actually closer to 1½ generations (as opposed to second generation copies) removed from the working master based on the minimal loss of running masters made on Paul Stubblebine's souped up 1-inch SOTA Studer C37 tape deck. So the next order of business was a call to Dan Schmalle, one of The Tape Project's co-founders, and the rest is history. The Tape Project is the brainchild of the unlikely trio of Dan "Doc" Schmalle, Michael "Romo" Romanowksi and Paul "High and Outside" Stubbleine. Dan is a multitalented, renaissance individual who has enjoyed a long term love affair with high-end audio. He started as a physics major at UC Berkeley and after graduation had a choice as Dan tells of "building bombs or audio equipment." After graduation, Dan took a job as a pastry chef though he always retained his interest in DIY equipment. Then back in 1990, Dan's interest in repairing radios led to him to open Classic Radio of Liberty Bay, a store specializing in restoration and custom modification of antique radios and vintage audio equipment. Then at about the same time Joe Robert's Sound Practices took off and the interest in single-ended tube amplifiers blossomed, Dan started publishing Valve, a magazine featuring DIY articles, tweaks and think pieces (sample articles from Valve are now online at www.enjoythemusic.com). Dan's other credits include starting the VSAC Show (Vacuum Tube State of the Art Conference) and currently he owns Bottlehead Electronics, a high-end audio company specializing in DIY kit building and single-ended tube amplification (though a music server is around the corner too). Paul and Michael in contrast, come from the professional audio side. Both are veterans of the studio business and have been involved in the recording and mastering of more analog and digital releases than one can count. Paul, unlike many of his professional audio colleagues, is also proud of his audiophile roots (his studio features all modified SOTA electronics and Magico speakers). Michael, a musician by trade, did studio work in Nashville before moving to San Francisco and working with Paul. When it comes to The Tape Project, the division of labor goes as follows. Dan handles The Tape Project hardware and reel-to-reel modifications, marketing (including the website and forum dedicated to reel-to-reel enthusiast). Michael's contribution to the project includes the production of Jacqui Naylor's album, the custom reels and packaging. Paul also wears several hats, one of the most important being A&R and title acquisition. As Paul relates, "he, Dan and Michael sit down and brainstorm about what albums they love." Then Paul approaches different record labels to gauge their interest in doing business. In some cases Paul shares, "the label is interested in a new format eg. making more money." In other cases, the record label wants to make sure that The Tape Project release doesn't overlap with their own reissue release plans. Another scenario according to Paul, "is that there is no playable tape (or other technical issues)." Sadly, some requested tapes were rejected because the software had deteriorated too far (the industry's lack of preservation of these pieces of music history strikes a raw nerve with Paul!) Paul is also an expert on old school tape mastering techniques and is in charge of producing the running masters and making all the decisions related to tape stock, tape equalization, etc. Step One: Procuring A Reel-to-reel Tape Machine To my knowledge, the Otari MX-5050 Mk.III with a price tag of around $6200, is the only reel-to-reel tape machine currently in production. But the lack of new reel-to-reel tape machines shouldn't prevent audiophiles from getting into The Tape Project. Plenty of gently used reel-to-reel machines are listed on eBay, Audiogon or even craigslist. Other sources of tape decks include used high-end audio equipment dealers, Jeff Jacobs j-corder.com or recording studios selling off some of their equipment. And of course Dan is always there to lend a hand in finding a reel-to-reel tape deck!

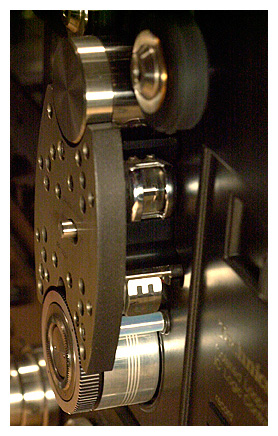

Now possibly most important decision one must make when buying a reel-to-reel machine is choosing between a professional or as Dan terms it, "a prosumer" machine. Among the many choices for "prosumer" tape playback include machines from Technics, Otari, Revox or Stellavox; then there are excellent pro decks such as the Nagra-T (Dan's pride and joy), Studers or Ampex ATR-100, 300s, etc. (one can even arrange to have the Technics or Studer machines, providing one has a little patience, rebuilt by the likes of Tim de Paravicini.) Then to playback The Tape Project Tapes, the machine must be capable of 15-ips, 2-track, ¼-inch playback. (The absence of an IEC/CCIR playback curve isn't necessarily a deal breaker issue if uses outboard electronics such as Bottlehead's Seduction or Repro tape preamplifier that provide for NAB/IEC equalization). Some additional factors that go into making that fateful decision include parts availability, condition of playback heads, quality of tape transport and ability to maintain head alignment. So if sound quality is the most important factor, and cost and having the dedicated space required to house such a piece is no object (plus a good service technician), then a professional reel-to-reel tape machine is the obvious choice. Since my Manhattan apartment precluded housing a pro deck, Dan recommended starting with the highly regarded Technics reel-to-reel deck because of its availability, three tape speed capability (3¾, 7½ and 15-ips), and ½ and ¼ track playback capability. In addition, the Technics's servo reel control system combined with dual pinch rollers and single capstan aids in maintaining constant tension on the tape resulting in stable, low flutter playback making it a gentle tape handler. Since I was going to use the Seduction (and eventually Repro tape preamplifiers), the Technics' lack of IEC equalization curve wasn't a drawback). My individual quest for the Holy Grail began with the purchase of a rebuilt Technics RS-1500US reel-to-reel tape machine (manufactured between 1978 to 1986 and retailing then in the neighborhood of $1600), from Jeff Jacobs at j-corder.com. Jeff, for those who don't know him, is a preeminent Technics reel-to-reel technician with over 35 years of experience as both a dealer and authorized technician for a number of audio manufacturers. While I paid a bit more for my Technics machine than if buying off eBay, I had the piece of mind that Jeff had completely stripped down, serviced (including replacement with upgraded brake pads), recalibrated and then bench tested my deck to ensure it met manufacturer specs. Furthermore, Jeff inspects and tests the tape heads; if they measure less than 70% of tip depth, he replaces them. For those searching for the ultimate, sexy looking reel-to-reel tape machine, Jeff also customizes the Technics reel-to-reel machines and gives them unique names like The Natural, The Pearl, Jade or Black Crown Jewel. Running anywhere from $4000 to $8000 (or more), these tape machines are unmatched works of art. Owners can customize their decks even further by adding some color matched Dark Labs NAB hubs and/or J-corder or Dark Labs customized reels to their machines.

Step Two: Hot Rodding the Deck After Jeff worked his magic on my deck, the J-corder Technics deck went to Dan at Bottlehead Electronics to eke out that last couple of percent of performance from my deck. These performance upgrades included hot rodding the Technics for use with outboard electronics and use of an after market high-end AC power cord, disconnecting the tape counter and upgrading the tape path. Every machine that comes into Dan's shop undergoes a rigorous inspection and replacement (if necessary) of any worn tape path and alignment of components in the tape path for straight and consistent tape travel over the heads and a flat, well centered tape pack on the reels. The Bottlehead tape path modifications also reduce friction on the tape surface and scrape flutter and make the tape sit a little closer to the heads when running in fast forward and rewind. "The end result" according to Dan, "is a machine that handles tape extremely well and sounds cleaner, with better low level resolution and snap and begins to approach the sound quality of a pro machine." But prior to carrying out any of the above modification, Dan adjusts the deck's brake tension. According to Dan, the one common problem he's encountered "is setting the correct brake tension, regardless of how new the stock felt brake pads look." After experimenting with different brake lining materials, Dan found a material that meets the tension specifications in both directions. All the decks that come into his shop have their brake pads retrofitted with this material. Dan also mentioned that, "it's remarkable how much better a RS-1500US works with the proper brake tension. The tension rollers never pop up at stop and the reels stop very quickly at runout. With the tape kept in good tension the pack seems to come out better when you stop and start a lot too."

The next order of business is aligning the ever so critical tape path. First, a careful visual alignment using some established reference points is a starting point for static alignment; the bulk of the alignment adjustment is made with shims. Then once the visual alignment is complete, the travel of the tape over the rollers, guides and heads and the tape pack position is noted. Dan has found that if the tape path alignment is done with enough care some sources of friction in the tape path can be removed and some guide surfaces can be replaced with lower friction materials resulting in subtle improvement in dynamics. Along with the tape path improvements, Dan also replaces any worn springs in the tension roller arm assembly and updates the tension arm roller bearings with higher quality ABEC 5 bearings, modifies two of the fixed guides to ABEC 5 ball bearings with abrasion resistant edge guides and removes other guides altogether. When this work is complete, the reel servo controlled tape tension is set to factory specifications. Finally, the head block is removed and a careful visual positioning of the heads is carried out. From there, the headblock is replaced and alignment with a calibration tape is usually pretty easy. In addition, Dan disconnects the tape counter because the belts create speed instabilities that degrade the sound. As Dan says, "You can tell how much the counter influences the smoothness of the reversing idler if you've ever heard the dreaded screech of the cheesy tape counter belts and pulleys when you rewind. The tape counter is not that accurate anyway." Last but not least, Dan hot rodded my machine for direct head output and use with the Bottlehead Seduction and the Repro tape preamplifiers. This modification is an absolute necessity for playback of The Tape Project tapes since the stock Technics machine lacks the ability to playback IEC/CCIR equalized software. Step Three: Adding the Outboard Electronics As alluded to earlier, the stock electronics inside prosumer machines leaves a lot to be desired and outboard tape preamplifier is needed to implement the IEC/CCIR equalization curves necessary for playback of The Tape Project tapes. The built to order Bottlehead Repro tape preamplifier is best used with medium to high inductance tape playback heads; it's optimally suited for the Flux Magnetics new extended response playback heads. To meet their primary goal of purity and neutrality, designers Schmalle, Joppa's and colleagues started with a pair of the extremely linear, high gain, low noise and sweet sounding EF86 pentodes at the input stage. Unlike the Seduction tape preamplifier, The Repro tape preamplifier doesn't suffer from gain associated issues since the Repro can be set up to with nearly 20 dB more gain than the 6DJ8-type triodes used in Seduction. The signal then passes through a direct-coupled passive EQ network to a 6DJ8 dual triode tube type; it's at this point where the Repro owner can choose either use the single ended output or pass the signal thru a 6CM7 gain stage to balanced transformer XLR outputs for balanced output.

One especially nice design aspect of the Repro is its rear "socket mounted" tube complement (as found with studio equipment) that allows for easy tube substitution and rolling. Furthermore, since the Repro uses only one 6922 tube, owners can scour the net or other tube sources for orphan single tubes to use in the piece (or a pair of NOS tubes go twice as far).

Inside the Repro's power supply, Schmalle and company utilize separate hybrid tube/solid state shunt regulators for each channel to tightly regulate the high voltages, resulting in they feel in a sense of bandwidth and separation unparalleled by other means of power supply regulation. Each signal tube is isolated from power supply noise by a Camille Cascode Constant Current Source (CCCS); the CCCS presents a high impedance load to the tubes resulting in isolation to power supply and running the tube at its fullest gain. This results according to Dan, "in a blacker background and an elevated level of dynamic realism." As we all know, the choice of coupling capacitors can make or break a tube unit and Bottlehead Electronics smartly allows Repro owners to choose their unit's coupling capacitors. For my Repro, I had Paul Birkeland who was building my Repro, install VH Audio's hideously expensive V-Cap TFTF Teflon capacitors. Now a word of warning for anyone considering using these, or any, Teflon capacitors. For the first 100 hours or so, the V-caps sound almost defective; around 300 hours of burn-in time is required for them to break-in. From what I've been led to believe, the extremely long burn-in time of Teflon capacitors is directly traceable to the "fluidic" nature of the dielectric; as a DC current is passed through the Teflon capacitor, the actual value goes up and microphonics decrease with time. As a consequence, the break-in time of Teflon capacitors greatly depends upon where they are used in the circuit eg. it might require years when the cap is used as a filter; when used a coupling capacitor, the Teflon capacitor breaks in more quickly, again depending upon the value of DC voltage across the capacitor. For the purposes of this review, the Repro tape preamplifier was used as suggested by Dan in a quasi-balanced configuration. George and Colleen Cardas of Cardas Audio built for me a special set of 3 meter Golden Reference interconnect cables with the Repro end outfitted with XLRs and the preamplifier end outfitted with RCAs (needed since both the conrad-johnson ART Series 3 and current GAT preamplifiers are single-ended). The Repro's single-ended option wasn't evaluated since I didn't have a long enough length of cable around plus the Repro's high single-ended 4 K output impedance (compared to the balanced 600 ohm value) makes cable length an important sonic consideration. George also built a 24-inch length of Golden Reference interconnect for between the Technics tape deck and Repro tape preamplifier. In this instance, the tape head's high impedance necessitates using a very short, high quality, low impedance interconnect between the tape deck and Repro tape preamplifier to avoid among other things, truncating the upper octaves. Finally, there's the question of the unit's stability. Since the Repro was obviously designed for rack mounting (17" wide x 3½" high x 4" deep), this piece is unstable when using heavy AC power cords or interconnects or placed upon tiptoes.

Initial listening sessions were carried out using the hot rodded Technics RS-1500US/ Bottlehead Seduction tape preamplifier combination. While this arrangement is infinitely better than the solid-state-ish sounding stock Technics electronics and a bargain at its $610 pre-built or $325 DIY kit, the Seduction is a huge sonic step below the Repro. The Seduction is definitely a touch dark and on the tubey sounding side, a little lacking at the extremes and resolution and doesn't have quite enough gain. The Seduction had a great soundstage and was rarely irritating sounding except when pushed (substitution of tubes can also address this issue). Next up was the hot rodded Technics RS-1500US/Bottlehead Repro combination. Now as good the Seduction is, the Repro is on a totally different level. We're talking about a bird of another color. The Repro, and one must allow at several hours of being powered on and/or playing music before critical listening, is extremely quiet and transparent, allowing one to resolve the minutest music details on The Tape Project tapes. (the tape deck too benefits from a couple of hours being on before playing.) Through the Repro/Technics combination, The Tape Project tapes display a soundstage limited only by the associated equipment and software. Instruments and singers have a much more realistic sense of body and realism. Strings are as sweet as sugar, if not gently rounded, without tipping over into euphonic territory. One can literally hear the violin bow changing direction and feel the pressure of the bow on the strings. Low frequencies are very dynamic though they could be a smidge tighter (Low end performance here is also a function of many other issues including the tape heads, the AC power cord used with the Repro and tubes used). The top end, which like the bottom end is very dependent on a number of other factors in the chain, is nicely extended and natural sounding, though it could be a touch more open. Step 4: Tweaking the Repro As mentioned earlier, the quest for the ultimate sound is facilitated by the Repro's rear socket mounted tubes. And, unfortunately, the more one listens to the best NOS tubes, the more one realizes just how wanting are the current generation of tubes. For one thing, the noise floor of the best of the NOS tubes is so much less than currently manufactured bottles so as to be silly (For some interesting thoughts on why today's Russian tubes don't stack up to their NOS counterparts, check out http://recforums.prosoundweb.com/index.php/mv/msg/16812/238372/0/#msg_238372) So the first tubes pulled were the stock Soviet 6K32Pi/EF86 Russian tubes and replaced with Telefunken EF86s obtained from Kevin Deal at Upscale Audio (later vintage according to what information gleaned from the web). The Telefunken EF86s were specifically selected because of their reputation as being extremely quiet (and staying quiet—as in the desirability of using the Telefunken EF806S with U47 mikes). And the Telefunkens didn't disappoint. They were more detailed and transparent and three-dimensional and resolved more harmonic structure and spatial information than the stock tubes. I also have since obtained two sets of rare Ulm manufactured Telefunken EF806S as well as some chrome plate Telefunken EF86 and GEC CV4085 tubes but haven't had the time to compare them to the currently used Telefunken EF86. Next up were the stock GE 6CM7 tubes. Here the tube rolling yielded an unexpected result. In all cases, the stock GE 6CM7s proved the best choice being quieter, cleaner, more transparent, extended and neutral than the two different pairs of Raytheons (black and grey plates) or a pair of Realistic manufactured tubes. The last tube left to experiment with was the Russian manufactured Electro-Harmonix 6922EH (not bad tubes as far as current tubes go and used by many high-end audio manufacturers). While far from an exhaustive study, I did audition several different brands of NOS tubes including a later vintage Siemens CCa and E188cc/7308 (gold pins), a Telefunken, Tungsram and Phillips PCC88/7DJ8 and an Amperex E188cc/7308 PQ, (early ‘' Holland vintage), Bugle Boy 6DJ8 (this tube might have had more than a few hours on it) and an E88CC Miniwatt. The hands down winner from this group of 6DJ8 tube types was the Amperex E188cc/7308. The E188cc/7308 was a very balanced sounding tube with a slightly euphonic midrange and rounded transient attack, good extension at both frequency extremes, outstanding resolution, microdynamic attack, three dimensionality and hall sound. Low frequency dynamics and detail were very good though wished they were even tighter and more dynamic.

Close on the heels of the E188CC/7308 was the Siemens CCa. These tubes were ever so quiet and transparent. Both frequency extremes rivaled if not exceeded the E188CC/ 7308. Each tube was very smooth through the midrange, the Siemens being just slightly overall better articulated but brighter in the upper midrange compared to the Amperex. In the end, this upper midrange deviation gave the Siemens tube a somewhat artificial sense of space. The Siemens E188CC/7308s also produced a nice sense of body and transparency but was even brighter than the CCa on massed strings and piano—and as we all know all too well, a little brighter is like being pregnant—either you are or you aren't. The other tube types just didn't cut the mustard. One of the biggest disappointments in the Repro, especially given the feedback surrounding these tubes, was Telefunken 7DJ8s/PCC88s (particularly since they don't cost an arm and a leg and are readily available, new, unlike the other tubes). For whatever the reason and maybe they just didn't work in the Repro circuit, the Telefunkens lacked resolution, midrange information—and especially dynamics when going head-to-head with the Amperex E188cc7308 tube. The Telefunkens on the other hand, were a little more neutral and transparent (eg. low noise floor) than the Amperex but not nearly as resolving of the soundfield enveloping the instruments and hall acoustics. Perhaps after all is said and done, the ultimate tube for the Repro might be a Telefunken E188cc/7308, an earlier vintage Siemens CCa or that rarest of tubes, a Telefunken CCa or E88cc? Time will tell. The Amperex Bugle Boy 6DJ8s sounded very pretty but musically slower and not as extended at either frequency extreme when compared to the E188cc/7308. That was a shame too since the BB 6DJ8s produced a simply amazing sense of the audience's conversations and moving around on the Bill Evans tape. Lastly, the three most disappointing tubes of the survey had to be the Phillips E88cc Miniwatts, the Tungsram and Phillips PCC88/7DJ8. First, the Miniwatt was definitely on the bright side and lacked low end extension. Next, the Tungsrams sounded ill defined and bloated in the lower frequencies and was far too technicolored elsewhere. Finally, the Phillips was also bloated in the low frequencies with an upper midrange peakiness. Needless to say, these tubes were rolled out the door. Tale of the Tape Make no mistake: the 15-ips/2-track Tape Project tapes bear no sonic or any other resemblance for that matter, to those 3¾ or 7½ ips, 2- or 4-track tapes your father played on his tape machine. The only format I've heard sound better are the original master tapes! While The Tape Project went through some growing pains in the first years with the delivery of their Series 1 tapes, both Dan and Paul promise those subscribers who hang in that "they have an ambitious, long term five year plan for the release of a large 15-ips tape catalog." Besides the tape speed, what really sets The Tape Project tapes apart from the older, prerecorded, "mass" produced, commercial tapes is the attention to detail. Every "i" is dotted and every "t" is crossed! These superaudiophile recordings are real time mastered at 15-ips (as opposed to the older 7½-ips tapes) using state-of-the-art tape transports, electronics and tape. The running masters are made on a specially modified, 1-inch Studer C37 tape machine modified by audio guru Tim de Paravicini (electronics) and Mike Spitz and Greg Orton of ATR Service Company (tape transport and heads). As revealed in a January 1995 interview with Bruce and Jenny Bartlett in Audio (http://ear-usa.com/timdeparavicini.htm), the legendary Studio C37 just also happens to be de Paravicini's favorite reel-to-reel tape deck. After de Paravicini is finished impedance matching the tape heads to his electronics, the Studer's sports (at 15-ips) an impressive frequency response of 7 Hz to 35 kHz (± 1 dB, S/N of 90 dB, rms weighted). All The Tape Project tapes are recorded on RMGI Studio Master 468 tape (Recordable Media Group Int., formerly known as EMTEC/BASF), selected by Stubblebine for its consistency, dynamic range over the full audio spectrum, minimal print through and long term stability. Stubblebine also chose to use the IEC (International Electrotechnical Commission) playback EQ since it nicely matches the losses of modern tape formulations, and the recording EQ doesn't need to make unnecessary compensation for overly boosted playback EQ. IEC is also a simpler curve to implement and gets the high frequency noise levels down to where noise reduction methods like Dolby and DBX become unnecessary. My Top Five Picks from The Tape Project's First Series of Releases

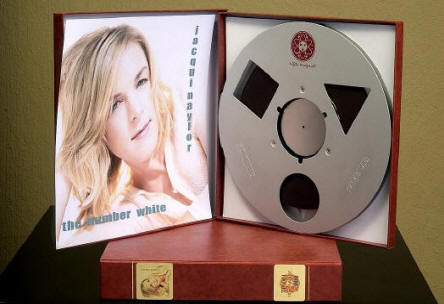

Max Bruch: Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46, Jascha Horenstein (conductor), David Oistrakh, (violin), The London Symphony Orchestra (Reel A)/Paul Hindemith: Violin Concerto (1939), Paul Hindemith (conductor), David Oistrakh (violin), The London Symphony Orchestra (Reel B); Producer: Erik Smith; Recording engineer: Kenneth Wilkinson; Recorded at Kingsway Hall, London, October 1962; Original release: Decca SXL 6035. The Tape Project TP-006. No Tape Project release better exemplifies their mission statement, "To make available to the discerning audiophile an analog listening experience that comes as close to the experience of hearing the master tape," than the Bruch/Hindemith release. The Bruch/Hindemith recording will test the moxy, subtlety and testicular fortitude of ALL high-end audio systems. And be sure to keep your volume control at arm's length! Both recordings feature simply stupendous dynamic range; so much in fact, that city dwellers will be constantly fiddling with the volume level so the neighbors don't complain. Here on the Bruch and Hindemith pieces, we find legendary Decca recording engineer Kenneth Wilkinson at his best in his and other Decca recording engineer's favorite recording venue, Kingsway Hall (known for its underground rumble and Kingsway filter). And it's no secret among Decca collectors that the Bruch/Hindemith is among the crème de la crème of all Decca recordings. As Wilkinson was quoted in a Michael Gray interview, "clarity, and quality, were what it came down to. You're trying to make a record sound as you hear the orchestra in the hall." Or as James Lock, a Decca recording engineer who learned his craft under Wilkinson's tutelage recalled in an interview in Grammaphone magazine, "we don't just make a recording in a place that happens to be convenient. We look for a hall and then make the contracts with the artists." And it's exactly those qualities that define this magnificent pair of recordings. Much of the success of Decca's recording success is directly traceable to the legendary "Decca Tree" microphone set-up. Lock described the Decca tree as "a bar about six feet long with the main left and right microphones at the ends and a centre mic suspended on a cross-bar about three feet in front. These are usually joined by a pair of wider spaced outrigger microphones to help cover the full width of the orchestra." The intent of this microphone set-up was to record the full spaciousness of the performance. On a recording such as this with a soloist, Decca would also resort to the use of a "reinforcement" microphone to balance the performer with the orchestra (M. Gray, arsc-audio.org/journals). Bruch's Scottish Fantasy on Reel A was written between 1879 and 1880 and dedicated (and first performed) to the Spanish violin virtuouso Sarasate, has its roots in folk music. Even the likes of The Penguin Guide raved gushed about the sound and performance of these two pieces gushing writing "The Oistrakh/Horenstein performance is very well recorded indeed, and the reading owes nearly as much to the conductor as the soloist. Oistrakh's playing throughout is ravishing, raising the stature of the work immeasurably. The slow movement (based the Scottish air "I'm a-Doun for Lack o' Johnnie) is especially memorable." (We will skip the inevitable Oistrakh/Heifitz comparison here!) Reel B with Hindemith's Violin Concerto is nothing short of sensational. Hindemith was known for recording many of his major works. Considered one of Hindemith's most brilliant works, written after he left Nazi Germany, and commissioned for the fiftieth anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, his Violin Concerto is best known as Edward Downes wrote, "the score is one exuberant flood of music in the spontaneous, uninhibited manner, one of Hindemith's most attractive traits." The Penguin Guide had to say About the Hindemith piece, "Oistrakh's performance here is a revelation. The recording is one of the very finest ever made of the combination of solo violin and orchestra." Both albums received three stars from the guide. (BTW, the Britten Violin Concerto on Decca is also a little known, superb Decca recording.) Of the two pieces, the Hindemith features slightly better sound and a greater sense of transparency and the recording venue. The highlight of both recordings is unbelievably sweet and realistic violin tone of Oistrakh's Fontana violin. High strings on the Hindemith work are nary a trace of hardness. While Oistrakh is clearly front and center on the recording, "particularly spotlit on the Hindemith piece," as observed by Stubblebine, it's not to the detriment of the rest of the orchestra. Paul added that, "this spotlighting was used in the original recording because of the low resolution playback quality of the audio systems in the ‘'; maybe this isn't done today." Of course artists such as Rubinstein demanded his piano be placed front and center on the recording for his audience. Interestingly on my much later vintage Decca Ace of Diamonds LP release (the last ED1 copy of this recording went for $717 on eBay), Oistrakh is more spotlit on the Bruch than on the Hindemith. This is a recording Stubblebine, "loves to cue up on his system." So do I and so should you. Bill Evans Trio: Waltz for Debby, Producer: Orrin Keepnews; Recording engineer: Dave Jones; Recorded live at The Village Vanguard, New York City, June 25, 1961; originally released as Riverside RLP 9399. TP-008. Waltz for Debby is widely regarded as one of the best piano jazz trios ever recorded—tragically ended by LaFaro's untimely death ten days later. There is an indescribable magic and electricity captured on this live Evans recording that is absent on his other masterful studio recordings. Now this wasn't the first time Paul had worked with the master tapes of Waltz for Debby and more than anyone, was well aware of the original recordings limitations. In fact, Paul revealed that Waltz for Debby was one of his (and my) all time favorite recordings. Paul added that, "one of the true highlights of his long career was having had the opportunity to actually work with Bill Evans." Now Waltz for Debby was made as Paul describes "under rough, location conditions," and the master tape requires both channel and frequency response rebalancing. Otherwise, Paul points out, "Evans' piano gets lost in the mix." Recording credit for both Waltz for Debby and Live at the Village Vanguard went to Dave Jones, a specialist in two-track location work (I haven't been able to find whether Dave Jones is the same engineer responsible for the excellent Connoisseur Society recording). Jones was recruited for this project since Keepnew's normal recording engineer, Ray Fowler, was out of town. Now a little about what went into the recording of this all time jazz classic. Not yet the star he was to become, Evans spent many hours practicing his craft at the Village Vanguard. On that day, Evans, starting at 2 PM, played five, thirty minute sets, that were forever recorded for posterity and then released on Waltz for Debby and Sunday at the Village Vanguard. Listeners should also notice on the LP –and to even a greater extent on the super high resolution 15-ips tape –a variation in the background audience noise and chatter from track to track. This is of course associated with whether the song was recorded in the afternoon—or later on in the evening when the audience started arriving. Although the recent and superb sounding 45 rpm Analogue Productions reissue of Waltz for Debby is by no means embarrassed by the 15-ips tape version, The Tape Project release simply sounds more realistic. Evans' piano in particular sounds far less mechanical on the tape compared to the LP version (this quality is painfully apparent on the OJC reissue). LaFaro's bass is more fleshed out and the playing even more defined on the tape compared to the LP. (The lows on the LP, as I find on many re-issues, are just a bit boosted compared to the tape). Cymbals possess greater body, weight, shimmer and decay. Not surprisingly, the tape has a much greater sense of acoustical space, a slightly wider soundstage, greater resolution and audience drone and chit-chat. Both vinyl and tape sources are exceedingly transparent with the tape getting the nod here. Bill Evans prejudice aside, Waltz for Debby is the second best Tape Project release, if for nothing else, the excellence of this reel-to-reel release showing some of the original recording's issues. Malcolm Arnold: Arnold Overtures, Malcolm Arnold, conductor, the London Philharmonic Orchestra; Producer: Christopher Palmer; Recording engineer: Keith O. Johnson; Recorded August 14-16, 1991, Watford Town Hall, London; originally released as Reference Recordings RR48. The Tape Project TP-003. Audiophiles with reel-to-reel tape decks are in for a real special treat with the release of the 15-ips tape version of Reference Recordings 1993 Grammy nominated recording (for best classical recording), Arnold Overtures. For the first time ever, audiophiles have a real opportunity to experience and appreciate Keith O. Johnson's genius. Or as Paul unhesitatingly shares, "Keith's recordings never stop giving one rewards as the playback system improves. That's unlike other recordings that have a ceiling and then begin to show issues in the recording." That genius includes on this recording, the use of Keith's own specially modified, focused gap reel-to-reel tape machine, microphones and electronics. For more on the making of Johnson's Reference Records recordings, readers are advised to check out J. Gordon Holt's interview with Johnson in Stereophile (vol. 7, no. 4, p. 56-71, 1984) as well as Robert Harley's interview with Johnson in Fi magazine (Harley's interview is posted on www.spectralaudio.com). (Unfortunately due to Keith's busy schedule, I wasn't able to get in contact with KOJ for this article.) On this RR recording, we find Arnold successfully conducting a selection of his own overtures including "Beckus the Dandipratt, the premier recording of "The Smoke" (a celebration of urban life), "A Sussex Overture" (written in 1951 for Herbert Menges and the Brighton Philharmonic Society), "The Fair Field" and "Commonwealth Christmas Overture." Unfortunately for some reason, The Tape Project didn't give the subscribers the same breadth of the original album details as with their other releases. Now I have to admit that unlike other critics, I could never work up any enthusiasm for the sound of the original Arnold Overtures LP. For some reason, I found (and still do) the orchestra amorphous sounding and lacking midrange weight. Upper octaves were lacking and glazed over sounding. Yes, the Arnold Overtures LP had wowie, zowie dynamics, big bass drums and was transparent sounding—but the heart and soul of the music was missing. Well I'm happy to report that the reel-to-reel release of Arnold Overtures solves almost all of these aforementioned issues. In contrast to the Evans or Suite Espanola releases where sound of the LP compares favorably to the sound of The Tape Project release, the original Reference Recording's LP is totally blitzed by the 15-ips tape. Yes, the Arnold release still could stand a smidge more in the midrange but I understand what sonic qualities are important to Keith. This 15-ips release simply exudes transparency, frequency extension and dynamic range. The most impressive sonic attribute of the Arnold Overtures tape release, however, is the Decca-like capture of the acoustical space of Watford Town Hall. And it's not a coincidence either. As noted in a 2005 interview in Mix magazine, Keith reveals he "models his setup after one used by longtime engineer Gordon Parry of London Decca Classical…," renowned for his Decca opera recordings. As scary good as this Tape Project release is, it's even more frightening to imagine just what's on that original master tape! The Robert Cray Band: False Accusations. Producers: Bruce Bromberg and Dennis Walker; Engineer: Bill Dashiell. Originally released as Hightone 8005. The Tape Project TP-004. For those not familiar with Robert Cray, he is considered by Blues: Keeping the Faith author Keith Shadwick, as "the center of the general revival of interest in the blues during the 1980s." False Accusations is perhaps the most underrated and overlooked release from The Tape Project. Tape Project head honcho Dan Schmalle echoing my sentiments said, "Yes, I agree about the Cray. I chose that one. When we threw on the original master to check it for condition, Romo [Romanowski], walked into the mastering room and said it was so real he had a flashback, complete with memories of the smell of the stale beer and peanut shells, from when he worked at a bar where Cray used to play." With roots in Buddy Guy and Albert Collins, this follow up to his hit album Bad Influence (also on High/Mercury records), features the likes of "Playing in the Dirt" and "False Accusations." Clearly a studio recording, this recording has a soundstage that stretches from wall to wall. The guitar riffs will make the listener want to pull out their own air guitar. While the sound does vary from cut to cut, all are nothing less than outstanding. Get this one while it's hot! Jacqui Naylor: The Number White, Producers: Jacqui Naylor and Art Khu; Recording engineer: Michael Romanowski. The Tape Project TP-001. This recording is both near and dear to Paul and the rest of The Tape Project team (see http://www.bottlehead.com/et/music/bday.htm). Sister album to Naylor's Color 5 release, The Number White was recorded at the Bill Putnam-built Coast Recorders by Tape Project co-founder Michael Romanowski with the capable assistance of fellow Tape Project collaborator, Dan Schmalle. The Number White was recorded with a variety of mikes including a Klaus Heyne modded Neumann U87 (see www.recforums.prosound.com/index.php/f/33/0/) on the piano and a Brauna VMI microphone on Naylor's voice. I'm going to part company with some recent critical comments about The Tape Project's first release. This recording Paul points out, "is not pumped up—nor does it have compression and its artifacts and sizzly reverb." The Number White is far from The Tape Project's weakest release (not that there's a bad one)—and whether these differences of opinion are due to the tape playback systems—is a superlative studio recording. And forget about comparing the CD with The Tape Project release, since each format underwent totally different processing, editing and ambient effects. Jacqui Naylor is best known for creating the style known as "acoustic smashes" where she sings rock tune over a jazz standard or vice versa. Naylor describes acoustic smashes on jazzreview.com as "we assimilate tunes because of their chord structure, so the band is able to play the groove of one tune, while I am singing the song." This is best exemplified on The Number White where Naylor sings the Gershwin standard "Summertime" over the Allman Brothers "Whipping Post" or Black Coffee, done to Led Zepellin's "Moby Dick." As with any good recording, the sound of The Number White continued to improve by leaps and bounds as the system was tweaked eg. after tube substitution and replacing my longstanding reference preamplifier, conrad-johnson's ART Series 3, with designers Conrad and Johnson's newest statement piece, the GAT. For example, my girlfriend Heidi, a trained singer, noted upon putting in the Amperex E188cc/7308 tube into the Repro that for the first time, she was hearing more nuances, depth and textures to Naylor's vocals. At the same time, the low end became tighter and better defined. Art's piano has a remarkably natural feeling to it. The two biggest sonic issues with this studio recording are a slightly closed-in feeling and a slight loss of transparency. As with the Cray and most studio recordings, the sound varies from track to track with the closely miked songs sounding generally better than the slightly more distantly miked cuts. Overall, one heck of a music experience and I can't wait to see Jacqui Naylor performing at the Blue Note in New York City in November! Honorable mention: Albeniz: Suite Espanola Fruhbeck de Burgos, conductor, New Philharmonia Orchestra, Producer: John Mordler; Recording engineers: Kenneth Wilkinson (balance) and Alan Reeve (recording), Recorded: November, 1967, originally released Decca SXL 6355. The Tape Project TP-005. Suite Espanola is another of the highly regarded and desirable releases from the Decca vaults. This album features noted Spanish conductor and Spanish music champion, Rafael Frubeck de Burgos at his best conducting eight Spanish Albeniz compositions. This album in distinction to many of Burgos' other recordings (that numbers over 80), features his own arrangements of seven of Albeniz's pieces taken from Albeniz's piano suites plus "Cordoba", taken from Cantos de Espana. Commended by the Penguin guide who had to say about this performance, "this is real light music of the best kind." Now I have never been as in love with the sound of this album as other audiophiles. Suite Espanola has a thin balance that was offset by the beauty of the music. As with the Hindemith, have to say that Decca LPs are a far better representation of the original master tape than companies such as Mercury or RCA or based on this review, Reference Recordings with the Arnold Overtures. That said, this album just exudes everything that typifies the Deccas. Tons of spatial information. Great percussion if not slightly highlighted. The opening "Castilla" for its castanets. Another winner from The Tape Project. The Tape Project tapes. Prices: Individual 15-ips/2-track tapes (two reels): $500; Selective subscription, Series 1and 2: $1800 for six tapes (can buy additional tapes @ $300 each; Full subscription Series 1 and 2: $3000 for all ten tapes. Note can't combine series 1 and 2 subscriptions. For further information, visit www.tapeproject.com or call (360) 697-1936 or email: [email protected]. J-corder/Bottlehead Electronics Modified Technics RSRS1500 USUS (Not currently manufactured; only available used), www.j-corder.com. Price: $3599. Bottlehead Technics modifications: Direct output: $100 alone (or free with purchase of an ATR frequency extended response tape head); Power cord modification: $95. Tape path upgrade: $600. www.tapeproject.com. Bottlehead Electronics Repro Tape Preamplifier: made to order, www.tapeproject.com, $4000. For the Teflon V-caps, add $764; Rel TFT: $544; Solen TFF: $512. Designers: Dan Schmalle, Paul Joppa, Paul Birkeland, John Tucker and John Camille. Cabling: Reel-to-reel to Repro: 24 inch Cardas Golden Reference single-ended interconnects: $816; Repro to GAT preamplifier: 3 meter balanced to single-ended Cardas Golden Reference cables: $ 2426. www.cardas.com . AC Power cords: ESP Reference. www.essentialsound.com. Price: $750. Technics RS-1500 US Reel-to-reel and Repro sit in a two shelf, Symposium Acoustics Isis rack, XT top shelf, Ultra interior shelf, one set of rollerblock modules and precision couplers. www.symposiumusa.com. Price: $2149.

|