You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE

january/february 2008

simon yorke

S9 Flamenco Record Player

as reviewed by Marshall Nack

|

What's this Englishman doing in Spain?

I initiated an exchange with Simon Yorke when I noticed strange droppings scattered around the drive shaft of the S9 Record Player's motor, looking quite like mouse residue. And I wanted to know more about that hieroglyph on the side of the motor box. Simon replied in characteristic form. The animal faintly visible on the side of the outboard motor is a bull, handcrafted by his artisan son Spencer using a process called blast etching. Each bull is unique and is there because it is "a potent symbol of Spain - our adoptive country—which we use to convey the origin of the S9 and acknowledge our assimilation into Spanish culture."

That answers the first and third questions. About the mouse pellets (see below), Simon says they are nothing more than "drive cord detritus—quite normal and not of concern—polyurethane rather than metal—a kind of dandruff, nothing more." Polyurethane dandruff from the drive cord? And so the tone of our discourse was set. In closing the exchange, Simon offered to specially endow the animal's reproductive parts for an unspecified surcharge. Sounds intriguing.

The Visual

It doesn't look like much. Stripped down and elegantly simple, it's about as basic as you can get. Its footprint is small, like the Kuzma Stabi or one of the lower model Basis Audio turntables. Sitting over there next to the V.Y.G.E.R. Baltic M turntable, which retails in the same neighborhood ($8250 for the S9; $7800 for the Baltic M), it is dwarfed. The included Yorke arm, purpose-built for the S9, looks just as insubstantial as the platter/plinth mechanism.

You approach for a closer look. All is properly understated and low-key. Few parts, all finished in variations of satiny silver-grey, except the black, solid graphite record mat. Come closer again. Now you note the craftsmanship. Fit-n-finish is seriously good, not something you've encountered at this price point. For example, from the listening seat you'd never know the platter is spinning—the finish is so even you have to touch it to be sure.

Terra Firma

Given the minimalism aesthetic and the impression of air and lightness, you wonder how will it sound? Will it also be that way—light, detailed and airy?

Fortunately, performance bears only slight resemblance to that description. The reality of its sound production comes closest to terra firma, not air or H²O. There's nothing small about the proportions of its soundstage or airy about the mass and density of its images. These image-objects are shuttled about with impressive speed and land in unwavering locations on the soundstage.

Frequency response is marvelously smooth and even. The blend achieves an uncommon level of coherency and integration so as to preclude dissection. The treble is just there and never gets strident, like the bass, which never gets boomy. Dynamic contrasts are likewise smooth and even, with stepless gradations.

But, in truth, the S9 favors the midrange—most of its energy is located in that band. Yes, it goes deep, but not in sufficient quantity to be notable; likewise, it goes high but you wouldn't call it particularly extended. It has these things in common with my reference Linn LP12, but even more so. So, while dense and solid and unwavering, it lacks the full weight of the earth.

One more thing, while we're picking on the LP12. The S9 has bloom and Tone—yes, with a capital T, big tone, like the LP12—and harmonic portrayals ring true, but it doesn't push these as far as the Scottish table, which tips over into the realm of a romantic coloration. Also, the images it produces are of consistent make-up from end-to-end. They are a homogeneous mass of tone and their flesh is taut. It doesn't project a halo or acoustic aura of different quality from the central core. Most importantly, the movement of images is accomplished in an almost ingratiating manner.

Yes,

wholly unforced. I'm listening to a Decca second pressing LP of

Gershwin's An American In Paris, with Zubin Mehta and the LA

Philly (SPA 525, blue label compilation. This cut is copyright 1976).

The wealth of information is spread out in a panorama, with the French

horns piping up from deep center-left, trumpets deep center-right,

trombones to their right, tuba to the trombones' right, wood blocks way

on the other side, extreme left, behind and outside the speaker, marimba

likewise extreme right. Want me to notate the rest of the

instrumentation, or is that enough? You get the idea—resolution leaves

nothing to be desired.

Yes,

wholly unforced. I'm listening to a Decca second pressing LP of

Gershwin's An American In Paris, with Zubin Mehta and the LA

Philly (SPA 525, blue label compilation. This cut is copyright 1976).

The wealth of information is spread out in a panorama, with the French

horns piping up from deep center-left, trumpets deep center-right,

trombones to their right, tuba to the trombones' right, wood blocks way

on the other side, extreme left, behind and outside the speaker, marimba

likewise extreme right. Want me to notate the rest of the

instrumentation, or is that enough? You get the idea—resolution leaves

nothing to be desired.

I note again how transients are never irritating. To a degree beyond the competition, edginess and glare are avoided. Images move about at a fairly remarkable clip, arriving instantly without fanfare or heraldry—I'm inspired to nickname the S9 "Sir Speedy." Once they arrive, the notes are given full expression. In no sense are they foreshortened to heighten the impression of speed.

Noise level is vanishingly low. Not just when there's no signal, but also even when there is: absent the kind of noise that likes to sing along with the music. And there's no breakup accompanying crescendos. This is about as quiet as I've heard with analog. SPLs ramp upward, unimpeded, and flip on a dime into the softest pianissimo, without faking it; that is, without disbursing telltale clues that would make you aware of the machine working to accomplish the effect.

Wonderful Shape!

The fleshy body occupying 3-D space, the full duration in time, the rock-solid positioning, the wonderfully assured and composed transients, the natural surface texture… All of the above lend these images a wonderful shape. The S9 has exceedingly well formed notes, the best I've encountered in a record player.

Also beyond the competition is the soundstage's stunning holistic quality. Everything happening upon it shares the same time/space dimension. Its surface is uncommonly of a single piece—like the real deal, natural. This is great for classical music and like genres, as long as you're expecting to be seated in the middle of a large hall at a distance from the stage. The S9 always puts the stage well behind the speaker plane. And it tends to push images towards the sides. (While the scale of the stage is the same on both tables, the Baltic M has more center fill, less on the sides. Ditto for the LP12.)

Levelheaded and composed, most everything you hear with the S9 is intended to be there. It's not uptight or stiff, just very purposeful. The S9's combination of control and composure is rather reminiscent of the gear from Lamm Industries, Inc. Sir Speedy has amazing grace.

It is here that the S9 ranks among the very best I've heard. It is terrific at the things that define naturalism. As for the rest of the audiophile scorecard, the S9 scores solidly Class A grades and gives no cause for complaint. However, the Baltic M has more deep bass and better resolution, along with a wider dynamic range.

Handel's Water Music, a fabulous late harmonia mundi LP with

Nicholas McGegan and his Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra (HMU 7010,

released in 1988), was convincing evidence of the S9's rather

well-developed imaging and luxe handling. My usual reaction to

this LP is mouth agape stupefaction at the way each instrument in the

chamber orchestra has its own pinpointed location on the amazingly

precise and vivid soundstage. As the music flows, so does the activity

on the stage; the thing is intensely visual. To my mind, this LP

cemented Peter McGrath's credentials: it is one of his finest

engineering projects.

Handel's Water Music, a fabulous late harmonia mundi LP with

Nicholas McGegan and his Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra (HMU 7010,

released in 1988), was convincing evidence of the S9's rather

well-developed imaging and luxe handling. My usual reaction to

this LP is mouth agape stupefaction at the way each instrument in the

chamber orchestra has its own pinpointed location on the amazingly

precise and vivid soundstage. As the music flows, so does the activity

on the stage; the thing is intensely visual. To my mind, this LP

cemented Peter McGrath's credentials: it is one of his finest

engineering projects.

Now, however, I'm not looking at the same stage.

The images are quite a bit larger and firmly anchored in place. Their borders are not precisely demarcated. (It's possible to talk about a precision soundstage but still have vague image borders.) And the notes are dancing as the melody is passed around from instrument to instrument—Sir Speedy is very good at that.

But the darn notes are staying around rather longer than I'm used to. It seems the S9 doesn't want to throw out short tonal bursts; it can't help but flesh them out, making them round and massive—and making them seem to last longer. What results is less of a pause from one note to the next, less inter-note silence.

Normally you can blame this on smearing; that would explain it. But I know this ain't the case now because the transients are beyond reproach, and it's not as if the decay has lost any quality. I mean, you put on one of those single-sided, 45-RPM Classic Records reissues, like Duke Ellington's Blues in Orbit (original Columbia CS 8241), and you can't believe the Truth and Honesty of what comes out. It doesn't sound at all loose or smeared anywhere. What's going on?

To the best of my understanding, it's more like the sustain part of the note has been elongated.

This actually contributes to the impression of luxury and sophistication. There's something svelte about the S9's fully developed images. It takes its time, and is not in any hurry. It sounds less hifi, as if some of the showy audiophile stuff has been tossed off.

As you can tell, I rather like the S9's take on things. But the debate raged. My opinion was not shared by significant others. They judged those same characteristics that I described as the S9s regal bearing as too reserved and distant, too clean, too English. All thought its dynamics were great, but yet they called it polite. Go figure.

Well, it's all a matter of taste.

Cosmetics and Setup

The Installation Manual is pretty good—and needs to be. While setting up the record player itself is a piece of cake, installing the cartridge can try your patience. Some steps are out of sequence: adjusting the VTF should be the last thing you do—after cartridge alignment. Also, to do this comfortably and keep your peace of mind intact, you really need two people.

The S9 like its big brother, the S7, is made of non-magnetic "austenitic" stainless steel, except for the arm-board, which is a multi-layer wood laminate. The S9 tonearm follows SME geometry, and is unique for this record player. Even the tonearm leads are sheathed in matching gunmetal grey colored dielectric. But I wish the headshell had a finger lift. This would facilitate positioning the stylus right where I wanted it over a track.

The lack of a suspension didn't seem to matter. I situated the S9 on the top shelf of my TAOC racks and placed a solid walnut soundboard from CORE Designs underneath. (These come with their CLD amp stands. It happens to be a nearly perfect size to cover the TAOC shelf.) Footfalls, gusts of wind—nothing disturbed the stability of the cartridge in the groove.

The motor runs quietly, if not silently—within a foot or so you can hear it whirring. It stays cool to the touch. After unpacking, let it spin for several days, maybe a week. That polyurethane belt needs to stabilize. After 50 hours it still had warble. Recalibrate speed every day during this time.

After two weeks check the cartridge alignment and that all connections are firm. At one point I had the experience of knowing the sound was deteriorating, but couldn't put my finger on why. Then one day when I went to swap cartridges all became clear. Unbeknownst to me, the headshell bolts had loosened and the cartridge was dangling loose on the S9's armtube. Yikes! Of course, this had to come to light when an important visitor was auditioning the system.

Power and its Conditions

It was necessary to adjust the sound using cables and AC conditioning (or the removal of such) to bring the frequency extremes into balance. Because of the S9's midrange favoritism, TARA Labs cables were de rigueur. Generally, the 0.8 interconnects were in use, to provide the needed frequency spread.

The motor is particularly sensitive to the origin of the AC. With the supplied AC/DC wall-wart plugged into a passive power conditioner, the TARA PM/2, some of the bloom was reigned in, and I gained control and focus, but the midrangy character was exacerbated. It was a toss up between the PM/2 and straight into my Ensemble Mega power strip.

The S9 can alternately be powered via a battery. This is easy to setup—just disconnect the wall-wart from the motor and replace it with the plug from the battery adaptor. (And disconnect it again when not in use, because even when not spinning, the battery sees a load and is draining.)

The battery power supply is literally just that—a nine-volt transistor battery hanging off a wire. It would be nice to have a matching holder for the thing.

Initially, this was really impressive. Running it on the supplied nine-volt battery dropped the noise floor drastically. It was already quiet but you could now sense a deeper well of blackness in the spaces between the notes. It was a little eerie—it reminded me of digital silences at first, with their digital black holes. There was definitely a greater signal to noise ratio and more separation. Sir Speedy attained even more grace. I'm told you can use a 12v battery for further gains—Simon uses a 12V 1,2Ah dryfit.

I never got around to trying that out, though, because the thing went and morphed on me the next night, when it became less noise suppressant and tonally brighter. It seems even that skimpy battery supply adapter has a burn-in period.

Upgrade Time

Audiopath Phono Ground Cable $49.95

Joe Fratus of ART Audio mentioned he had a ground wire he wanted to ship to me. He didn't say why, just took down my requirements: spade on one side, alligator clip on the other, four and a half feet long.

It never ceases to amaze me, how the most unlikely tweaks often turn out to make a significant difference.

I can hear you now, "No way! You're telling me this ground wire changed the sound? But everybody knows it's nothing but a piece of wire conductor, isn't that so?"

I connected the Audiopath Ground Cable to the S9, let the record player warm up for one side of an LP, and then listened.

The S9 didn't sound like it had the night before. I ran to get that Handel Water Music LP.

Fixed!

Would you believe the duration of notes shrank, nearly matching the Baltic M or the LP12, and that the stage moved forward and image borders firmed up? Dynamics were popping so that ordinary vinyl acquired the characteristics of a Direct To Disc LP, possibly to the point of being a tad aggressive. I noted there was a change in timbre—not any additional bloom (I didn't want that). It got a little brighter and had increased accuracy regarding the ID of the instrument. With the Audiopath Ground Cable, the S9 lost a goodly portion of its luxe and regal qualities.

Audiopath's designer Tom Hills says the big difference between his product and the typical stock ground wire is in the termination quality. The wire itself is no big deal, simply a tin copper braid, but he uses good silver solder and Cardas (or equivalent) spades. He's very modest. Audiopath cables are made by Hudson Audio. Prospective S9 owners should definitely check this out.

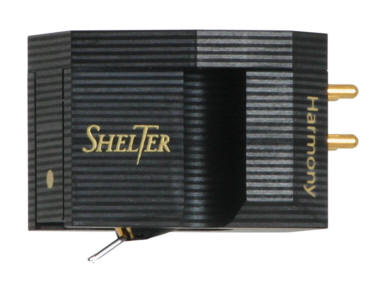

The Shelter Harmony $4000

Midway through the audition, along comes the new, top-of-the-line moving coil Shelter Harmony cartridge to replace the Shelter 9000 on the S9. This is a Shelter with a twist. The cartridge body is constructed of layers of carbon fiber—a Hero Boy, multi-level sandwich of carbon slices. It begins life as sheets of carbon fiber, which are put under 60 tons of compression pressure. Then a little plastic is applied to bind it, and the body is laser-cut, giving it crisp edges and an overall dull finish.

When the 9000 model recently replaced the best-selling 90X, I noticed the Shelter house sound was changing. While much is the same, the 9000 brought more focus and less warmth. The Harmony travels further along this path.

First impressions generated a string of adjectives. Speedy. Quiet. Clean. Dark. There is the same evenness of frequency response, the fulsome body and image size. Be aware, though, the Harmony is much darker than the 9000—although the top is extended, there's less light and air. But the big news is the noise suppression achieved with the carbon-reinforced body, which is purported to decrease vibrations. You'll hear less breakup and a broader dynamic range. Even better, the noise reduction accounts for a huge boost in resolution. There are tons of explicit dimension cues: if they're on the recording, you'll hear them in playback, and hear more of them on familiar recordings than before.

Huge amounts of hall echo are revealed. It's almost overdone. In one fell swoop, your room will seem to have acquired four $ figures of room treatment.

This cartridge comes with a Carbon Fiber Damping Disc, a thin sliver of carbon that fits on the spindle between the LP and the record weight. This'll give dynamics and focus another boost—great, if you need more firming action. Between the included carbon fiber screws and the Damping Disc, the Harmony is like a resonance damping system. When I used the Damping Disc I removed the Audiopath Ground Cable—taken together, they were too much.

The Harmony is the best cartridge yet from an important analog house.

Conclusion

A big trend in contemporary turntable design is the massive, overbuilt, statement super-table. The Simon Yorke S9 Flamenco Record Player is almost a rebuff to those big boys, as if Mr. Yorke set out to prove that great results could be had with a minimum of parts and complexity. As Simon put it, "The intent with the S9 was to reduce and simplify both the language and construction of the S7 - to make for a more affordable, simpler machine and refine 'the aesthetic'." (The S7 is his bigger, more expensive, flagship model, soon to be replaced by the new S10.)

The minimalist S9 conjures aesthetic reactions first. This is abetted by a quality of craftsmanship borrowed from a much higher price point. The reality of the physical thing dwells more in the realm of art object than in the marketplace of consumer goods. With a design concept at this level of execution, the S9 is somewhat intimidating.

Like my reference Linn LP12, the S9 is warm, with big Tone, well-developed bloom, and stellar PRAT. Both tables play favorites with the midrange, however, it doesn't take these as far as the LP12, except its midrange preference. It was necessary to make adjustments using cables and AC conditioning (or the removal of such) to bring the frequency extremes into balance.

And like the V.Y.G.E.R. Baltic M recently reviewed here, the S9 has very low noise and minimal mechanical tracking artifacts. You'll hear deeply into the source.

You can think of the S9 as dwelling between these two others with some of the better characteristics of each.

With the fleshy body occupying 3-D space, the full duration in time, the rock-solid positioning, the speedy transient and the ever-present composure, the S9 has exceedingly well formed notes, the best I've encountered in a record player. And the same can be said for the holistic nature of its soundstage. These aspects taken together not only seem natural, they create a luxurious, regal impression.

But these same qualities get in the way when notes should be rendered shorter. The S9 cannot help but flesh out images. It has trouble producing short bursts of tone. Consequently, on familiar recordings there is less pause between notes, less inter-note silence; they seem to last longer. Mostly for this reason, I strongly recommend S9 purchasers audition the Audiopath Ground Wire, which had the surprising effect of shortening notes and ameliorating some of the S9's regal bearing. Then again, you may very well enjoy it as delivered.

Cartridges? My other unqualified recommendation is pairing the S9 to the Shelter Harmony cartridge. This was a huge step up. Other cartridges recommended by the importer are the Van den Hul Frog and the Audio Note Japan IOM. Marshall Nack

S9 Record Player

Retail: $8250

Simon

Yorke Designs

web address:

www.recordplayer.com

US distributor

Sounds

of Silence

14

Salmon Brook Drive

Nashua,

NH 03062

web address:

www.soundsofsilence.com

email address:

[email protected]