You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback

ISSUE

3

Stan Ricker: Live and Unplugged, True Confessions of a Musical &

Mastering Maven, Part 3

by Dave Glackin

For those loyal readers who made it through Parts 1 and 2 of our interview with Stan Ricker, here is your reward: Part 3, the last! For those of you who just tuned in, the introduction is repeated below, to set the stage for this portion of the article.

Introduction

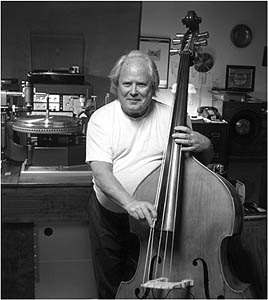

Stan Ricker has a unique combination of knowledge of music, recording, and mastering, and is one of the few true renaissance men in audio today. Stan is a veteran LP mastering engineer who is renowned for his development of the half-speed mastering process and his leading role in the development of the 200g UHQR (Ultra High Quality Recording). Stan cut many highly regarded LPs for Mobile Fidelity Sound Lab, Crystal Clear, Telarc, Delos, Reference Recordings, Windham Hill, Stereophile, and roughly a dozen other labels, including recent work for Analogue Productions and AcousTech Mastering. Stan is particularly well-known to audiophiles such as myself who were actively purchasing high-quality LPs during the mid-70’s to mid-80’s. Stan’s love and knowledge of music has stood him in good stead during his mastering career. His long experience as both a band and orchestra conductor has trained him to hear ensemble and timbral balance, which has proven to be exceptionally useful in achieving mastered products of the highest caliber. Stan has played string bass (both bowed and plucked) and tuba from the fifth grade through the present, and he turns out to be something of a bass nut. Watching him play his stand-up acoustic bass in front of his Neumann lathe with "Stomping at the Savoy" playing over his mastering monitors was a special treat for this writer (writing for this estimable rag does pay, just not in cash). Stan also has a love of pipe organs, and is quite knowledgeable regarding the acoustical theory of pipes. He has a lot of great stories, and is known for speaking his mind. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Music Education from Kansas University, but his prodigious mastering skills were self-taught.

As the capstone to his career, Stan has gone into business for himself with the creation of Stan Ricker Mastering (SRM) in Ridgecrest, California. He has a state-of-the-art Neumann VMS 66 lathe with a Neumann SX-74 cutter head, a Sontec Compudisk computer controller, a Technics 5-speed direct drive motor, and console and cutter head electronics designed and built by none other than Keith O. Johnson. Stan now specializes in less-than-real-time mastering from digital sources (DAT, CD and CDR) onto 7" or 12" 33 rpm or 45 rpm LPs. The lacquers that Stan cut for me speak for themselves (he’s once again on the cutting edge...). He can also handle analog tape, up to 14" diameter reels of half-inch tape at 30 ips. By day, Stan is the head buyer for the Telemetry Dept. at the Naval Air Warfare Center at China Lake.

Stan has been called "iconoclastic" (The Absolute Sound, Vol. 4 No. 14, 1978), "pleasantly cantankerous" (Stereophile, Vol. 20 No. 6, 1997), a "crusty curmudgeon" (by Bert Whyte) and "the most understated renaissance man of audio" (Positive Feedback, Vol. 7 No. 1, 1997) by yours truly. Stan is all this and more, as I’m sure his wife Monica will attest.

I have wanted to do this interview for several years now. Our first session was held in Ridgecrest on 21-22 Dec 1997. We continued on 7 Jan 1998 on the way to WCES in Las Vegas, which proved to be a refreshing respite from the hypnotic blur of countless Joshua trees whipping by at X + 10 mph. We concluded on 31 Jan 1998 back at Stan’s place. Each time, all I needed to do was wind Stan up, let him go, and have a rollicking good time with the man who was once quoted as saying that "conformity is the high road to mediocrity."

Continuing with the JVC Days

Earlier in this article, we left our hero in the middle of his career at JVC. We now pick up that story...

Dave: Stan, you did all the Telarc LP’s, and all the Soundstream stuff, right?

Stan: I did an awful lot of Soundstream stuff. All the Delos stuff, the first six of which I not only mastered but did the original recording on.

Dave: (Holding up an LP) This a recording I absolutely love. Let’s see, it is Delos 3005, Susann McDonald, World of the Harp.

Stan: Yeah, Susann McDonald’s harp. That’s the fifth out of the six. (Reading the credits) Chief Engineer, Stan Ricker, Disk Mastering Engineer, Stan Ricker.

Dave: I’ve played this record for a lot of friends. I’ve had it playing at dinner and people were saying they’ve never heard reproduced sound that good. And I should point out that this is a digital recording, mastered onto an LP at half speed. So there is a lot to be said for the process of taking digital on to an analog medium. It’s an absolutely enjoyable disk. So you did the recording on that as well as the mastering?

Stan: Yeah, yeah. I had three B&K microphones and a portable Studer model number 169 console which had its own internal battery power supply. The output of the 169 fed the input of the Soundstream Digital Machine, which was a 50k, 16 bit machine. The 169 ran on batteries during recording and then you could turn on the charger during breaks.

Yeah, this (World of the Harp) was really neat. And I had spent a lot of time with Susann and the geometry of the room to basically record the harp in almost mono and the room acoustics in stereo, and used only two of the three microphones.

Dave: So you did the engineering and the mastering for the first six Delos LPs. Well, I’m gonna go out and find them all now. And here’s one of my all time favorite records on Crystal Clear, Capriccio Italien and Capriccio Espagnol with Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops. You did the mastering for that one plus a lot of other orchestras.

Stan: Yeah, but look who was here with me: Mastering Engineers, George Piros, Stan Ricker and Richard Simpson. We had three lathes there. Richard brought his AM-32B lathe and the VG 66 amplifier rack. I was using Crystal Clear’s lathe which was, I think, a AM-32B, but it had a SAL 74B amplifier package. But I think the cuts that actually got released were the ones that were cut by George. He was using an Ortofon lathe with an Ortofon cutting system on it, which was very good, indeed. The cutter’s delicate, and so is its sound. Ortofon cutters tend to burn out easily, but that was a good choice because there’s almost nothing in this particular recording that would have challenged the cutterhead very much because the orchestra played in such a reserved mode of operation, they were all scared that they were going to do something wrong, that they just kinda half played. They never really got into this, they just kind of played. They didn’t play with great vigor and, what’s the word, panache?

Dave: Well, maybe they were scared of the direct disk process.

Stan: I think so, in fact, I know so!

Dave: Something you can say about these Crystal Clears is that they were all direct to disks, so you were sitting there doing your mastering in real time.

Stan: Yes. In real time, in a real room, and we used the Soundstream Digital Recorder as a back up in case none of these came out. See, here it says: "Mastered with a new Ortofon DSS 732." So yes, it was George’s product that actually got released. That’s nice. There’s so many European recordings that were cut with the Ortofon system that sound superb.

Dave: Okay. Here’s one which Stan absolutely loves, Virgil Fox, The Fox Touch, Volume 1 on Crystal Clear, which was direct to disk, organ with all the stops pulled out.

Stan: Oh yeah, that was fun. That was two B&K microphones hard-wired through a minimalist console that John Meyer had put together. The microphones were B&K with special power supplies and line driver amplifiers built by John. The console fed the 2 Neumann lathes directly. Richard Simpson was there, too, with his VG-66/AM-32B Neumann. That was a lot of fun to do. I wish we had that much challenge nowadays, direct-to-disk recording. But that was then and this is now and things are different.

It was from that experience that I asked John Meyer to build for me the power supply and pre-amp that I later used for the Delos recordings. I had already bought three B&K microphones. He did all this other outstanding stuff and it was because of John’s really determined persistence with these B&K microphones, and the outstanding recordings produced, that B&K finally got into the commercial microphone manufacturing business. John, and a gentleman named Dick Rosmini, who died last year, were responsible. Dick was quite a studio recording engineer and musician. He used a lot of quarter-inch diaphragm B&K microphones on acoustic guitars. Nothing in the world like the transient response of a quarter-inch mic. Just so pristine. I mean a microphone as delicate as a headphone, you see. Really nifty.

Dave: Now you mentioned you had all the scores memorized for those pieces (the Virgil Fox organ recordings)?

Stan: Yes, I’ve known all those pieces by heart since my High School days. I have the recordings over here in what is now a CD collection, but what used to be a record collection. So I knew the pieces well. I knew their dynamics and registration. So that made it a whole lot easier to just adjust the pitch and the depth together. It would have been really neat to have this Compudisk computer there because then all I’d have had to do was deal with what size groove I wanted and the computer automatically takes care of the pitch corrections. That’s pretty neat. So, anyway, we did separate pitch and depth control on the Neumanns, and I had worked out a chart ahead of time as, "Well, if I’m cutting a four-mil groove, considering it is random phase, how far apart do I have to have the grooves so that under the wildest consideration of modulation, they would not collide with one another?" So, it was just worked by trial and error with some test tapes before and then when Virgil was practicing. Most of the time I figured, when he was playing really loud, we would cut a seven mil groove and 70 lines per inch; we wouldn’t have too much trouble that way. Then, when he’s playing really quietly, we adjust to 400 lines, two mil groove.

There’s so few people who understand the phrase—you listen to the news, and they’ll say, "Man, the guys in Panama are really pulling out all the stops to find out who did this." And there’s so few people who know what ‘pulling out all the stops’ really means. (Laughs) This recording on the Rufatti instrument, ole’ Virgil really pulled out all the stops! You know, he made some really powerful music with this thing—so much so that we had several visits from the local police during our late night recording activities.

Dave: For this you put your lathe in the back of your ‘59 Ranchero and drove it down to Garden Grove?

Stan: Yeah, took part of it down in the Ranchero and took part of it down in a rented Ford station wagon, I remember that. Took two loads of stuff down. This lathe wasn’t "my" lathe, it was JVC’s lathe. It was the same lathe that I was using to cut all the half-speed product on. In order to cut at real-time, we borrowed a set of the Neumann real-time plug-in RIAA equalizer modules from RCA. The JVC Cutting Center and the RCA studios were both located in the RCA Building at 6363 Sunset in Hollywood.

Dave: So, instead of the King’s Way Hall Subway, on this one you’ve got sirens, right?

Stan: Well, one of ‘em that didn’t get released that was really funny was one when we had a police helicopter do a fly-by. We heard this, Whop-whop-whop-whop of the rotor blades and then suddenly the music stopped and Virgil says, "Oh, shit!" real loud, you know. If I’d kept that lacquer it probably would have been the only example of Virgil Fox’s spoken voice on record. (laughs) Yeah. He was really going great guns when this particular helicopter came-a whop-whop-whop-whopping and it really reverberated inside the church!

The organ was a really great instrument to record and it was a really fun recording session. The pitch-depth settings on the lathe went anywhere from 70 lines per inch to 440 lines per inch, like this, you know, and I know it’s gettin’ louder, Hrmmm, Here we go! Increase the depth, decrease the lines per inch. Then what was neat is both controls turned the same way to achieve the opposite effect. That what was really cool. Clockwise on the depth gave more depth. Clockwise on the pitch knob gave less lines per inch. And they were both relatively linear. They could have been Gilmer-belted together if the knobs on both were the same size. You could have done with just one knob, you know.

Dave: So they really blew the roof off what is now the Crystal Cathedral.

Stan: Yeah. Made lotsa woofers that day! WOOFER CITY, USA! Lots of really good soundin’ music. Now, the Volume II, do you have that record, too?

Dave: Yes.

Stan: That’s the one with that Piece Heroique on it, composed by Caesar Franck. There is this alternating F-sharp and B in the pedal, boom, boom, boom, boom, it simulates a timpani. Because the alternating pedal speaks fast enough, you get the mixing of these two discreet frequencies in the air, in the church. And so you have the resultant beat-frequencies going between these two notes and there’s a lot of really low frequency stuff going on. (B = 29 Hz; F# = 21.75 ; let the reader do the math.) Oh, you’ve got Dark Side of the Moon here. (Stan Co-Founds Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs.)

Dave: Yeah. Some of the most famous things you cut were for Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs. And you did a lot of those while you were working for JVC and you did a lot of those later, when you left JVC to go full time. You were one of the three founders of Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs, right? In ‘79, along with Brad Miller and Gary Giorgi.

Stan: Right. Brad Miller and Gary Giorgi. I had the technical stuff that we could market, you know. They seized on that. Somethin’ that sounded good, maybe we can sell it. So I provided the technical know-how on which it was all based and they provided the other stuff, as in tapes, hype, BS and publicity. Ya know, all this good stuff. They were great talkers for the product, going out and shmoozing people and so forth. That was needed. And then, Herb Belkin got involved. Herb first got involved because at that time, when this was just starting up, he was running ABC Records and Brad had managed to lease, I think it was Katie Lied. Who was that band?

Dave: Steely Dan.

Stan: Steely Dan, oh yeah. Anyway, we made test pressings. I remember that I took one of these white label test pressings with red JVC letters "JVC Test Pressing" and just laid it on Herb’s turntable and put the stylus down and turned it up and waited. And he said, "Well, when you gonna put the record on?" I mean it was so quiet. And then the music started comin’ out and he was like, "Holy Shit! What did you do? Did you re-mix this album? You didn’t have my permission to re-mix this album, you know. How come it sounds so good?" It really piqued his interest ‘cause it sounded SO GOOD! Then pretty soon he left ABC and, as they say, "came aboard" Mobile Fidelity. They then changed the name to Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs to differentiate it from Brad Miller’s Mobile Fidelity Records, which was so named because Brad recorded trains and planes like at Reno Air Races and things like that. So those sounds were very mobile. Sometimes the recording gear itself was mobile, being either in the airplane or on the train. So you often got the recording from two points of view. If you’re on the train and you’re approaching the crossing, you hear the bell go, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding—you really hear the Doppler effect (rise and fall of pitch) as you go by this clanging gate-crossing bell. So, the Sound Lab thing was a different entity than was Mobile Fidelity Records.

Dave: And, while we’re on true confessions, I will confess to having listened to Mobile Fidelity’s The Power and the Majesty quite a bit in the late seventies. It had the trains on one side and the thunderstorms on the other.

Stan: Oh yeah, sure. The Power and the Majesty. I loved doin’ that. Man, that just starts from ground zero, I mean totally quiet, and then you hear, chh, chh, chh, way off, I mean, like far off. This choo-choo, man, and he just comes chuggin’ right through your living room! And, ohhh, that horn!!!! What every trombone player needs to know in terms of breath support!! You put the gain control on your playback device at what appears to be a reasonable level at the beginning. When you get to where the train’s going through your living room, you think you’ve been run over by the train! There’s a hell of lot of dynamic level on that recording. Brad Miller did a super job with his original recording of that.

Dave: You’re not kidding. I played that for a lot of unsuspecting visitors in the seventies. (laughs) They felt like they had been mauled. It’s the kind of thing that gives being an audiophile a bad name. But I will freely admit to loving MoFi 004.

Stan: Yep. That was quite a good one—I love it, too.

Dave: So, the other labels you recorded for, I’ll just run through them and see if they ring any bells... Columbia, Diskwasher, Klavier, London, MCA, Phillips, RCA, Telefunken, Warner Brothers, and then you did all the early Windham Hill’s up until...

Stan: Up until Bernie Grundman started doin’ ‘em real time, and that happened when Windham Hill turned their distribution over to A&M, which was a big bonus for them because when A&M said, "Hey, we’ll take on your line of records and distribute them," I mean, their sales went up phenomenally. Then they said, "Well, oh, by the way, if we’re gonna do this, then Bernie’s gonna have to cut these things." Well, okay.

He’s one of the very best at real time cutting. That’s for sure. But real time cutting with a lot of high frequency content really, no matter who’s doing it, the physics of it are very difficult to overcome.

Dave: I think perhaps this record is your favorite of all time. The Star Wars and Close Encounters on MoFi with Zubin Mehta.

Stan: Well, it’s certainly one of my favorite MoFi things. There’s a number of reasons why it was one of my favorites. The recording team from Decca, when they came to the United States to do this, invited me. Jimmy Locke and Michael Mails and Simon Eaden, I had known them all from my previous work with Decca, cutting stuff, and so when they came to L.A. to record Zubin Mehta’s orchestra, they invited me to come to the recording sessions. So, not only was that a real gas, but when we got to this Cantina Band, this cut 4 on side one, it was basically a dance band. And they weren’t sure how to mic it effectively. So, on that one, that’s my mic setup. We’ve got some brass here (left), and we’ve got some saxophones here (right), and we had a guy over on the side (hard right, at the forward edge of the stage) playin’ the steel drums, Jamaican steel drums, you know, and the problem was how to mic it so it sounded realistic and also ‘stereo-like’. So, at one time I had three different, mastered versions of this same album. We had our half speed of this, and the English release of it, which was real time mastered, an English pressing which was very good, and there was a third one, the regular American London, which was real time, but pressed on American vinyl. And they were all quite different in the way they sounded. Of course, this one sounded the best!

Dave: Of course. Nobody would argue with that.

Dave: You were at Mobile Fidelity Sound Labs from ‘79 to ‘83, and you mastered all of their LPs up until April of ‘83, right?

Stan: That is correct.

Dave: Another famous LP, or set of LPs that you mastered for them is the Beatles’ Box. Is there anything special you wanted to say about the Beatles’ Box? What the experience of handling the Beatles’ master tapes was like, how much they were insured for, how they got here, so on and so forth?

Stan: Well, what I really like about the Beatles’ tapes was, as probably with all EMI tapes, how well their use was documented. Each one came in a flat tin can, a mu-metal can, and taped inside was a log of when the tape was made, when the original was made, when the two-track tape was made, when it was edited, who edited it, who put the leader on it, and how many times it was loaned out, to whom and for what reason, which was neat; for us (MoFi), or American Capitol, or dubs for European distribution, or whatever. Except for the stuff that EMI released off of those tapes, everything else was made from tape copies of those originals. That’s why the Capitol things that were released here in the U.S. sounded so different, indeed, from the original. The copies weren’t all that very good.

One of the things that interested me was that with some of the earlier Beatles’ tapes the voices singing were all on one channel, and the instruments were on the other channel. And it’s not what you’d truly call stereo. It was, in fact, two mono tracks which were originally designed to be combined into a mono release. But we found these things very interesting in their original form. So a discussion grew into, "Well, how do you think we ought to release these things? Should we be true to our format and say, we’re gonna release ‘em exactly as the tapes are, or we’re gonna release ‘em exactly like the original records were?" Well, we really didn’t want to release them exactly as the original records were. One of the very interesting reasons for that, among other things, was that the MoFi cutting system was dedicated, hard wired stereo. There was no mono switch on this thing at all. I’m sure I could have easily enough rigged up some wiring to make it mono, but we thought it would be really interesting to release the records as the tapes really existed. And we got into kind of a discussion. "Well, geez, you think we ought to call them up and ask them?" or something like this, you know.

The net result was we placed a phone call to George Martin to find out, "Well, sir, do you have any preferences, or do you care?" or whatever, you know. And the tone of his answer was that he seemed to be quite much burned out on Beatles stuff and really didn’t give a rat’s behind what we did with it. So we elected to cut it exactly as the tape format presented itself. And then later I heard that Mr. Martin bitched vigorously about "Why the hell did you release it that way?" And I believe my answer to it was, "Well, earlier I phoned you up and asked you and you, in your words, told me you didn’t give a shit what I did with the things." "So," I said, "It’s a little late now to complain about it." He agreed and so, rightly, it is. That was the end of that hassle.

But the tapes were extremely well engineered, they were just marvelous things to work with. And, of course, the acetate tape was brittle and one time, the tail end of one of the numbers just shattered all over the cutting room floor. Well, I mean that makes it sound really bad, like spilling a bag of potato chips and then walking on them, you know. It wasn’t that bad. It was probably a length of tape, maybe six or eight inches long, but it fractured into something like 200 tiny little pieces, so it took the better part of a day to put it all back together.

Dave: Your friends in the Sapphire Club tell me that was the first note of Michelle.

Stan: Is that what that was? I enjoyed Yellow Submarine a whole lot. I thought that was really cool. And what was the one, the Sgt. Pepper was fun to do. A lot of interesting recording. What’s the one, "Will you love me when I’m sixty-four?"

Dave: Mmmm. You’ve got me. I’d have to go back and look. A couple of my favorites were Revolver and Rubber Soul, but it’s hard to remember what was on what album now.

Dave: Stan, in April of ‘83, you left Mobile Fidelity for personal reasons, right?

Stan: Yes, I did. I left for the reason that my former wife was terminally ill. She had a very advanced case of pulmonary fibrosis, from which there is no known relief. We had great medical expenses that the insurance for a small company like Mobile Fidelity just simply couldn’t handle. So I chose to leave to find better insurance, which you have to do by working for a larger company.

So, I could only think of two large companies, General Motors, or maybe Ford, or the U.S. government. China Lake Naval Weapons Center was just sixty miles over the hill from Lake Isabella, where we were living, so it was a natural thing to come here. I applied here in May of ‘83 and was hired on May 29th of 1984. Shortly thereafter, my medical insurance took effect, which was really perfect because Mr. Belkin had been gracious enough to give me an extended year’s medical coverage, even after leaving the company, and gave me six months’ separation pay, so that I didn’t have to go on welfare. And all that was extremely, well, much appreciated. And my medical coverage here at China Lake took over the day before the MoFi medical ran out so we literally had seamless medical coverage during that transition that had to be an Act of God. I mean it was typical of my stay here at China Lake. My first day of employment, May 29th, was a holiday. I got paid for the holiday, Memorial Day! In reality, it was the stress of seeing my wife just disintegrate, and watching her fight with those damned insurance companies that caused my departure.

Dave: Well, Stan, thanks very much for sharing that with us and certainly, thanks to Herb Belkin for everything he did.

Stan: Yes. It was a little act of graciousness that went a long way towards making a very difficult transition doable.

Dave: I know you did go back to MoFi twice between ‘83 and the present, once in ‘86 and once in ‘95 when they started doing LPs again. But it doesn’t sound like either of those stints was too long lived for you.

Stan: No, it didn’t work out too well. In ‘86 MoFi had, by that time, moved to Petaluma in Northern California. That was after my trip to Moscow on behalf of Sheffield Labs with Keith O. Johnson, and I went as a second engineer when we went to record the Moscow Philharmonic, digitally and "analoguely." Mmmm. How do you spell that? It just didn’t work out at that time with MoFi. I wanted to be more than just a lathe slave. But that was not to be. So, I just had to not do that anymore. I came back here to China Lake and then MoFi started doing their LP’s again in ‘95.

I didn’t know MoFi was doing this and I saw a CBS News piece, Eye on America. It was a report on a Friday evening. "Would you believe it? Some record companies are still making records." And here was a real nice presentation of Mobile Fidelity’s new plant in Sebastapol, and cutting room, and I was really impressed. I thought that was a really good presentation that they set up for CBS. So I called up MoFi and I left a message on the answering machine. I told Herb that I had just seen this thing on CBS news, and I said, "I’d be real proud of that. I thought that was really good." And, "Congratulations" and "Keep workin’ on them there LP’s," ya know. It couldn’t have been more than a few days when he called me up and asked, "Would you like to come up and cut some records?" And I said, "Sure. We’ll do as we would a contractor." And he said, "Yeah, that’s what I mean."

So I went up there, maybe every other weekend or once a month, something like that, for a while. I went up there and cut a bunch of LPs on the system which now had Nelson Pass’s amplifiers in it, the Aleph 0’s driving the Ortofon cutting head. MoFi had taken out the Ortofon amplifiers and put in the Nelson Pass amplifiers. This is a really good cutting system. Cuts excellent LPs. So, I did that for the better part of a year and it was really easy because all I really had to do from here was drive seven miles out to the Inyokern Airport and take a United Shuttle to L.A.. Then from L.A. to San Francisco. And I could leave here at six and by quarter to ten I could be at MoFi. Really, very fast, direct connections that way. Either they would pick me up in San Francisco, or I could ride a bus up to Santa Rosa. But the real cool thing was to take the United Shuttle plane to Santa Rosa and they would meet me there. And they were just six or eight miles down the road from the Santa Rosa Airport, so that worked out real well, indeed. Unfortunately, the weather often bombed-out that Santa Rosa flight.

That was when I was last cutting for Mobile Fidelity, and then they stopped doing LP’s. That’s the last of the LPs for Herb until I can convince him to do an LP off of a digital original on this system here, and at less than real time. (.675 speed = 33 cut at 22.5 RPM)

Dave: There you go. Are you listening, Herb? We sure hope so.

Stan’s Days at AcousTech Mastering

Dave: Stan, would you tell us about the work you did with AcousTech?

Stan: Well, yes. I was called to go help with the installation of this system and then cut some stuff for Chad Kassem (of Acoustic Sounds) on the system, which Chad bought from Dave Wilson. It is a solid state system with the exception that the cutterhead is driven by Audio Research V140’s. Chad had all these new re-releases that he was doing, and so I cut quite a bunch of them on that list. Amanda McBroom, two albums there, Junior Wells, Sonny Boy Williamson, two albums. I really enjoyed Sonny Boy Williamson.

Dave: Ditto.

Stan: The one called Keep it to Ourselves. Yeah, that was really neat. I enjoyed that a whole lot. Gene Ammons, saxophone player, two albums there. That was really nice. Jimmy Dee Lane; that’s an original recording. Then, Otis Span, and there’s others. I wonder if we left that Acoustic Sounds Catalog outside. (After retrieving it from the porch) "Collect them all," it says. "The Revival Series." "A lacquer for each Analogue Productions ‘Revival Series’ was cut by Stan Ricker, using the state of the art Wilson Audio Custom Tube Mastering System recently acquired by AcousTech Mastering, a joint venture between Acoustic Sounds and Record Technology Inc." Seventeen albums here. Sonny Boy Williamson, Otis Span, Albert King, Art Pepper, two or three of them, yeah. Sidney Maiden. Ah, now this one, The Alternate Blues. Now this was a really bizarre thing. This tape came shipped in a fourteen inch tape box. So I told Chad, "I can’t cut this because the Studer tape machine will only take twelve inch reels." So I said, "You’d better take it down to Doug (Sax, that is)." So he took it down to The Mastering Lab and Doug called me up and he said, "Hey, guess what? That’s on a twelve inch reel!" I mean, I didn’t even look in the box. I mean, you talk about dumb. I was dumb! And Chad said, "Why didn’t you look in the box?" And I said, "I don’t know. I’ve never seen a box of X dimension with a smaller reel inside. Just never ever come across it." So it never occurred to me that anything like that would be. So, anyway, that one, Clark Terry, Freddie Hubbard, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Peterson... the Alternate Blues there was cut by Doug at his Mastering Lab. He did a hell of a job on it, too!

Dave: Yeah, I really like that. In fact, I brought that along.

Stan: Oh, good. You have? Oh, good. Well, we can hear it.

Dave: Great recording.

Stan: And then Sounds Unheard Of!, I really like that one. That one was recorded dry, and I had to add echo to it. That was my first experience with the Lexicon 300 as an echo machine. It does right well for itself. I diddled around with it to where... I wanted two kinds of echo. It’s just the way I conceived of it. Like these guys playing on a nice big stage in an empty concert hall. So, you have one set of acoustics which is the relatively rapid first reflection time, you see, of the stage environment, laterally and vertically. But then you have a longer time period of the reverb that you’d hear out in the hall. I know this from standing in front of a band or orchestra on a stage.

A perfect example of that is here at the China Lake Auditorium, which seats 1,100 people. The acoustic on the stage is a nice live thing, but it’s a whole world separate from out there in the hall where the people would be. When you’re conducting a group, when you’re standing right on the edge of the stage, you’re in that unique, in-between zone. So you can hear what’s happening in front of you, and you can hear what’s happening, reverb-wise, behind you. And that was the way I perceived that album of these 2 guys up here making this magnificent music. So, there’s two sets of echoes on this record because the machine was capable of generating two entirely different sets of echo time concepts.

I didn’t really know how it sounded until I played it back here on my system at home. I’ve got to say I was really impressed with it. Now, John Koenig, who oversaw that recording, and some of the others that were on the Contemporary label, he thought there was too much echo and he said, "Well, it doesn’t sound like the original." He’s in a unique position to know because his dad, Lester Koenig, was the owner, founder and producer of Contemporary Records. Sounds Unheard Of!, Shelly Manne and His Men, Curtis Counce, those albums for sure were ones that Mr. Koenig had to do with. And John had grown up around his Dad’s recording studio doing this stuff. But, with all due respect to John, I really didn’t want to make it sound like an EMT echo plate or anything like that because, as I told him, "I like doing reissues, and I think I do them well, but part of what reissues are all about is bringing out the best of yesterday’s recordings with today’s technology." And I didn’t feel I could just turn my back on the possibilities that the new reverberation devices offer; just making it sound like a couple of echo plates or dry rooms didn’t cut it for me at all. But it’s the kind of recording that also would be very interesting with no reverb added at all, because the raw tape is extremely dry.

You have only two persons on that recording. You have Jack Marshall playing the guitar, and Shelly all around, with his whole battery of percussion instruments. And it’s a very interesting thing, just totally dry. I would love to recut it on this system here in a totally dry mode. That would be an absolutely phenomenal demonstration record of really good sounds of what the various percussion instruments really sound like, intelligently played. I mean, Shelly doesn’t just bash the crap out of all this stuff, you know. He’s somebody who plays very musically, very tastefully, and I’d love to get that tape back and redo it here. I think of all these that I did in this revival series, Sounds Unheard Of! and Sonny Boy Williamson’s Keep It To Ourselves, were the greatest records!

Dave: Keep It To Ourselves is my favorite blues recording.

Stan: Mine, too, and I had the great pleasure of cutting all of these.

Dave: I wanted to ask about the Miles Davis box set which you cut at 22.5 rpm, instead of doing it at half speed. I know there was a reason for that choice.

Stan: There were multiple reasons for that choice, as you will hear. I enjoyed cutting on that system, especially in the beginning, just for the simple reason that it had been over twenty years since I had cut anything at real time. And it was truly nice to sit there and dig the music. That was nice. But the system is low powered and it had a tendency to produce slew rate distortion on high frequency transients, which you can hear on Sounds Unheard Of!. So, when the Miles tapes first came in, I listened to them and here’s Miles’ trumpet with a Harmon mute in it. I thought, "Oh wow, what trouble we’re gonna have with this." In order to cut it clean it would have to be cut at a very low level.

Dave: The Harmon mute is famous for frying cutterheads, isn’t it?

Stan: Well, it’s a real nasty thing to pass through any audio system. If you want to check any aspect of an audio system, just play a trumpet with a Harmon mute near it. The mute tends to subdue the fundamental, and all that’s left out of the trumpet tone is the harmonics. So when the guy plays this, he doesn’t hear very much, so he instinctively blows harder. So there’s a lot of harmonics coming out of the horn. It’s kind of like, if you want to see how good a P.A. system really is, and you think you have it tweaked out just right, just take a set of your car keys and jangle them in front of the mic. Listen to all the crunching, crashing distortion as it comes out the loudspeakers in the hall. Then you get an idea of the impulse type of high frequency energy clusters, tone bursts, going through the system, that it just can’t handle.

I knew there were at least three reasons why we couldn’t do Miles at half speed. Number one was because the AcousTech system is transformer coupled; at the input of the console, the tape machine, the Studer output goes into a set of Dean Jensen transformers right at the input of the Neumann console. So that would tend to make it less than acceptable, in terms of the bass response. Just like the way the bass response was rolled off in the original JVC mastering console before we made it DC coupled. There were other transformers in the system; the output transformers of the Audio Research amplifiers, as they connected to the Neumann cutterhead, and the transformers that coupled the feedback windings back to the input of the Audio Research amps.

Anyway, we’ve covered two reasons why we couldn’t do half speed at AcousTech. A transformer in and a transformer out of the system. So that was a real killer, in terms of bass.

Two other reasons, which were even more important, were that we didn’t have half-speed NAB playback on the tape machine, and we didn’t have half-speed RIAA record in the cutter system. So I said, "Well, we’re gonna have to make a decision here, because Chad really wants to do these things. So, the only other option is somewhere between half speed and real time." Well, twenty-two and a half is just about as half way between sixteen and two thirds and thirty-three and a third as you can get. And it’s a speed that’s instantly available on almost every Neumann lathe because, although Gotham Audio and most mastering engineers wanted to poo-poo half speed mastering, just the fact, to me, that Neumann made the speed available, which was a half speed of forty-five, meant that Neumann engineers themselves saw validity in half speed mastering of difficult program material.

So I decided, "Well, let’s try this half-way speed thing." I think I started at seven in the morning by phone, with the help of Krieg Wunderlich from Mobile Fidelity. He knew where the circuit was in the Studer tape machine motor servo control to change 15 ips to about 10.25, or whatever it was I figured out was needed. So, I found the circuit and it took me a long time to find the mixture of resistors to tune the oscillator circuit down to the point where I had some plus and minus speed control on the pot that was in that circuit. I got it just right, and it’s really easy to do that.

It’s the same way I did it in this system here. All you have to do is take an alignment tape, or a test tone, 1,000 cycles, and record it on the lathe at real time. You record about five or ten minutes worth of this stuff at thirty-three and a third. Then you change the lathe to twenty-two and a half and you play the record you just cut, the lacquer, you play it back on the lathe with the tone arm that’s on the lathe. Now it’s coming out at 0.675 of what frequency that you recorded it. So you listen to that, you hook the lathe playback arm up through one channel of the loudspeaker, pick left or right; the other channel, you listen to your tape playback on. You just zero-beat tune the damn thing. It’s just like tuning a piano or guitar. You tune the speed of the tape machine down till it’s zero-beat against the signal in the other channel; you can see it on the scope when it finally stabilizes and gets rock solid. That’s all it takes. So, it took, as I say, from seven in the morning to two thirty in the afternoon for me to get the speed right.

After that, it took all of half an hour for me to work out what EQ I had to put into the Sontec equalizers in order to get a musical product out the other end. I just used the same process that I used at JVC and MoFi. First, I’d cut a flat, that is, no EQ, a flat transfer of one or more of the pieces, parts of it, where the trumpet was, the piano, the bass was and the sax, so I could listen to the balance and I’d say, "Okay, the top end needs a little more. (Cupping his mouth) The trumpet sounds a little muffled, (takes his hand away) and the bass is real weak." Now what do I have to do to fix that? I’d think, "Okay, I need this, this and this," if it were real time. But, because I’m changing it by the ratio of .675 to one, now I have to transpose these frequencies in my head.

This is where the sense of perfect pitch comes into play, along with knowing what frequencies are involved with what keys. So you apply the transposed frequencies to the Sontec equalizer, which has many, many frequencies close together, and then just fine-tune it until, when you made a cut at twenty-two and a half and played it back at thirty-three, number one, the musical balance sounded correct, number two, the recording level was up to snuff. So, at twenty-two and a half with that system you could get a lot more power onto the records. Those records are recorded equal to, or hotter than normal because the two-thirds speed process allowed me to get more power (3 dB) on the record before the cutter system started to go into any kind of distortion at all. And you want as much level as you can get, consistent with not clipping, or not distorting. You always want to try to keep your signal up on a disk to get the best signal-to-noise ratio. That way, when people play those records, the music comes out loud and the background appears to be very quiet.

These are some of the reasons why it was done at twenty-two and a half. Sonically, musically, it took me half an hour to figure out what sounds I wanted. But it took me from seven in the morning till two thirty in the afternoon to figure out how get the speed thing accurate.

Dave: So the half speed didn’t have enough bass, and the real time just didn’t sound good enough.

Stan: The real time was just loaded with distortion at the top end of the trumpet spectrum. We made a test pressing of what the system would do at real time versus what it would do at the two thirds speed. There was like, very little, if any comparison. The real time thing had a little bit more, as Chad put it, "air at the top." But how much "air" is there in a mono recording? The point is that the cymbals and the brushes were just a little bit brighter on the real time cutting. I could have put in some more at the top end of the spectrum with the Sontec. But the trumpet sounded so damn good the way it was. And the trumpet was the main reason we were doin’ this album. So, I said, "Well, at the risk of not having as much extended top end, I’d just like to concentrate on the accuracy of the trumpet and the sax, and the bass was rich and full. I just want to leave a quite excellent thing alone".

Dave: I would imagine that these are the best of the releases of these Miles LPs that have ever come out. You’ve got the originals, you’ve got the OJCs, what else have you got? I don’t think you’ve got anything else.

Stan: A lot of people have asked me, "Gee, how’d the engineers handle it when they originally cut this stuff?" Well, they used high frequency limiters, they used overall limiters, and they used filters. Knock down the top end. Knock down the bottom end. Furthermore, these records were cut before the RIAA EQ was adopted, so the hi-freq pre-emphasis wasn’t so severe. It was a fairly forgone conclusion in those days that you can’t put a lot of that stuff on the record, unless you put it on at a real low level.

Now, a good example of a real low level, which I have here, is the previously-mentioned Columbia recording of Les Elgart’s band, which pretends to be a location recording (Les Elgart On Tour; CS 8103). It’s got applause and night-club type sounds mixed in. And the band really sounds great and this thing sounds no more like the typical Columbia recording than anything you ever heard. But that’s the sound that was possible with a Scully- Westrex system when you didn’t use any limiters in it and kept the level down so that you didn’t get any of those DC offsets, power supply thumps that occurred which caused cutterheads and power amps to have all those low- frequency thumping noises. You listen to it and you say, "God, I wish all of the Columbia recordings could be that nice." It’s a low program level. You can tell because there’s like six cuts per side and it still finishes at 6 3/8 inches on one side, and 7 inches on the other, you know. That’s totally non-standard Columbia operations. You could get a recording of this kind of quality at real time, but you have to keep the level down. You can’t just keep saying, "I want it hotter, I want it hotter."

Dave: I should ask why you parted ways with AcousTech.

Stan: Well, we didn’t really part ways. I was just hired as a contractor. I was not an employee. I was really getting tired of driving the 400 mile round trip every other weekend. I was also getting tired of the problems we were having with the other work we were doing besides the good guy (audiophile) stuff for Chad. People would send in dance tapes on digital format and the bottom end just wasn’t solid. It was just kind of loose and flabby. And some of these people would call up and say, "Well, have you listened to the tape? Does the record sound like the tape?" Well, the record sounded a whole lot like the tape.

It turned out that part of the problem was that we weren’t recovering the digital information all that well. There were an awful lot of recuts and I know that Don (McInnis), of course, was justified in wanting to make money on this system and between paying me a good rate of pay and putting me up in a hotel on the weekends, things like that, and all these damn recuts that we were having to do because of customer dissatisfaction with the product, it was frustrating to the max to all. And I know it had to be frustrating to him because it was just money going out and he wasn’t seeing a profit or happy customers, either.

I guess this is what happened because, looking back on it, we never really talked about it, it’s just that one day Kevin Gray started cutting there, I wasn’t invited back, and that was the end of it. In fact, when I went to work there one day, the only reason I knew something was happening was that I could tell that somebody had diddled with the lathe. It was like, "What the f--- is goin’ on? Who was messing with the lathe?" Some little bird told me, "Kevin Gray was in here yesterday cuttin’ on the machine." Then he said, "I don’t know what’s goin’ on." Don never talked to me about this. He just didn’t call me any more to come back and do any more work for him.

Now, I don’t know if he discussed this with Chad, or if this was just strictly a decision that he made by himself. I know that Chad still seems to think highly of me, which is nice. But I don’t like the feeling that there’s some kind of a bad feeling between Don and me. I feel really badly about that because if you don’t communicate about what has happened then it’s bad news all around. I had talked to Don about the possibility of getting another set of solid state amplifiers for doing these dance records with the kick drums in them, etc. We talked about that quite a bit, and just using the tube amplifiers for Chad’s work, or when some other customer might want a tube amplifier to drive the cutterhead. I thought it would be a nice option to be able to go either way, especially if you can enhance the product either way. To my mind, you don’t want to compromise the product. Some folks would or wouldn’t care, or couldn’t hear the difference.

So, I didn’t leave because I wanted to, that’s for sure. I would like nothing better than to have a long-term continuous working relationship with RTI, because before Don McInnes bought the company from Bill Bauer, in fact, even before Don worked for Bill Bauer, I had helped Bill over the years with many aspects of that record pressing plant.

For instance, how to get rid of the orange peel on the pressings without using spray glue between the back of the stampers and the record dies. We experimented with it a lot and came up with a 0.003 - 0.005 mil mylar sheet that goes between the back of the stampers and the die face. It takes a little longer to press the records because, with the heat transfer and then the cooling water transfer, you’re going through a barrier both ways with the mylar. So, the heat transfer to and from the vinyl is slower than it would be if you just placed the stamper on the metal die, you see. But we worked out things like that, and what are really the RIAA standards for phonograph records and that kind of thing.

There was a time when RTI was pressing those Armed Forces records after Keysor-Century lost the government contract. I had helped them a lot in getting the standardized weights and things like that for the records, because the more the records weighed, the more they cost to manufacture and ship. It was a trade-off between too skinny a record and too fat a record which cost more all around. I’ve been a staunch believer, supporter and advocate of Record Technology ever since they opened some 25 years ago and I really would like to continue that. I know, without a doubt, they’re the best record pressing plant in the United States. Even today, without hesitation, when asked about the highest quality pressings in the States, I ALWAYS toot the horn loudly for RTI. There may be some excellent pressing plants in Germany or elsewhere in Europe, but I don’t think there’s any place anywhere that’s the equal of RTI!

So, I can’t think of anything I’d be more happy doing than having a long-time, good working relationship with RTI. Right now it doesn’t exist, but I wish to hell it did.

Dave: I know that fairly recently you were asked by Stereophile to do some mastering for them, specifically on their Sonata LP. How did that come about?

Stan: I think it came about because Chad called them up and made a deal that no one could refuse, although it was certainly a highly logical place to do a piano recording. It’s a very random phase recording. If Bernie had cut it I think that he might’ve cut it hotter than I did. But it was right on the verge of tracking-problem breakup at the level we cut it. There’s so much vertical in that recording, in fact, it is totally random-phase.

I have to admit that the tape which was, I believe, 96 K, 20-bit from a Nagra certainly sounds better than the CD that came from that recording. I asked for a CD so that I could listen to it and get to know the music better. That way I’d know what I was going to do with the lathe. The CD didn’t impress me a bit, but the original tape was quite good, indeed (the music-making was really excellent). We transferred it from the Nagra through a Mark Levinson pre-amp to get enough gain to suit the input needs of the Neumann SP272 mastering console.

I don’t recall where the D-A conversion was done. I guess you’d have to read the info on the record jacket; probably it’s done inside the Nagra. The Nagra just had XLR outputs, as I recall, so it had to have been analog out of there. It looked funny because the Nagra had five inch reels of what just looked like quarter inch audio tape on it. But the tape wrapped around a large helical-scanning rotary drum. The tape moves at about seven and a half inches per second. Reminds me of an old Ampex PR-10! But the music that came out of that system sounded quite good.

Stan Ricker Mastering

Dave: Stan, you now have your own mastering facility here in Ridgecrest. Can you tell us a little bit about what equipment you have set up here at Stan Ricker Mastering, and where it came from, and so on? You’re located here at Ridgecrest because you work at China Lake...

Stan: China Lake Naval Weapons Station, or as they call it nowadays, China Lake Naval Air Warfare Center, Weapons Division. Big, long gobbledy gook of a name which we abbreviate as NAWC—Naval Air Warfare Center.

Dave: And you’re the lead buyer for the Telemetry Department.

Stan: Yes. And its an interesting and mighty fine group of people to work with, and they’re smart. Most of ‘em have Master’s Degrees in Electrical or Mechanical Engineering and a lot of practical know-how, too.

Now, back to this magnificent mastering machine, which started life as a Neumann VMS 66. My first knowledge of this machine, this lathe itself, was when Bruce Leek was mastering on it at IAM, cutting a bunch of stuff for Telarc on it. He cut a lot of other stuff on it also. At that time the cutterhead was being powered by Crest amplifiers. And then when IAM, which was International Automated Media, went out of business, this lathe system was sold to Keysor-Century Corporation. They used it for a while cutting Armed Forces Radio Shows and then Tam Henderson of Reference Recordings, Keith O. Johnson and I went to Keysor-Century and looked it over, as Tam was interested in acquiring a cutting system.

Tam wanted my opinion of whether this would be a usable device for his products. And I said, "Yeah, if we can redo the cutting amplifier rack." So Keith did. He tried to work with the Neumann VG-66 stuff but it just turned out that, in his words, he said, "This thing is intolerable. We’re going to have to start from scratch." And so he did.

Keith eventually came up with that chassis. It’s a line driver stage as well as feedback circuitry. It has cutter drive level. It has low/mid EQ: one dB per step. This control is where it transitions from constant velocity to constant amplitude (4 choices of turnover frequency). And then this control is high frequency peaking or attenuation at 12 kilohertz. It’s in half dB steps, and there’s EQ calibrate for those high frequency peaks. And this is the RIAA switching, on or off for testing. And this is the amount of feedback that’s required to make the cutterhead as linear, frequency wise, as possible, and it turns out to be 9 dB. These two controls here are feedback monitor level. There’s two sets of coils in the cutterhead here on the lathe. There’s the coils you drive to produce the music, and there’s a secondary set of coils (feedback coils) which send the corrective signal back, out of polarity, into the front-end of the Spectral drive amplifiers, to correct for non-linearities in the cutter system. This is the heart of the "servo-ing" of the cutterhead behavior, especially in the low end.

This feedback circuitry is totally transformerless, unlike all other systems that are advertised as being "transformerless". The signal is tapped off the feedback circuit so you can listen to the cutter, to know that all is well. All that the Neumann VG-66 stuff in the rack does now is contain the temperature-sensing circuitry that disconnects the cutter if it gets too hot. So, this new electronics package is very, very carefully built of all high quality components. As you can see, it’s totally a one-off, hand wired, hand designed, hand built unit by Keith. The output of this drives, through George Cardas Cables, those two Spectral amplifiers down there at the bottom, which are mono-block design. They have a bandwidth of something like DC to light! They actually have a power bandwidth of DC to 1.8 megahertz, -3 dB. Slew rate is 1,000 volts/ microsecond. They’re very, very fast amplifiers.

Dave: Fast in terms of slew rate?

Stan: Yeah, yeah. Fast and clean. And they have very low source impedance so they handle the cutterhead very well. The cutterhead drive coils which, as I recall, are 4.6 ohms. This amplifier package handles them quite well.

Nowadays, it’s the worst of both worlds because so many of the contemporary masters are submitted to me either as a CD or a DAT. The DAT may be a 44.1 or it may be a 48K. When a client calls me up to ask my preference, I say, if you can make the DAT at 48K, so much the better. It never hurts. Every little bit of resolution enhancement is useful. Taking that format and putting it on the disk at most cutting facilities makes all us mastering guys really worried about frying the cutterheads because the heads aren’t made anymore. It costs anywhere between $6K-$8K to send one to Germany to have it repaired, plus you’re off the air for that amount of time if you don’t have a backup. There’s a backup cutterhead here, but it’s not an SX 74. It’s an SX 68, which has not the power, not the magnet strength, not the transient response, and not the frequency response of the SX 74.

Most disk mastering people will put in filters and limiters and whatever else they may have, because it only takes just a little bit, one little bit too much of the high end—too high and too loud, too much heat—to fry the cutterhead. Most of the cutterhead safety circuits in the amplifiers aren’t all that fast. When Keith built this system, it was built as a dedicated half speed system. What I’ve done is modify it so it will cut at either 0.741 speed or 0.675. And what that means is I cut a 33 1/3 rpm record at 22 1/2, and I cut a 45 rpm record at 33 1/3. And that’s done by means of this Alesis XT digital piece of gear which is an eight-track variable speed recorder whose basic format is 50.1 kilohertz sampling, and it’s a 20 bit machine. So I take whatever is given me and transfer it to that machine, and it’s a variable speed machine so I can slow it down the required amount.

If you record at the fastest speed, and then drop it down to its slowest speed when you play it back, it’ll drop it what we call a major third in music. It will drop it from A major, say down to F major. Or it’ll drop it from C major down to A flat major. But when you’re going to go for an LP, you need to go down to 22 1/2. The reason that speed’s chosen on the lathe is obviously that it’s half of 45 rpm, and it’s a speed which has existed for years on many lathes. For example, that’s a spare lathe over there that we got from Tam (Henderson) in the deal, an old AM 32. And it has half speed 45, and it has half speed 33 in addition to the regular two speeds, plus it also has 78 rpm like this lathe does. So they both have five speed capabilities. And so, if you want to drop something down far enough so that you can record it at 22 1/2 rpm, it has to go down a musical fifth. It has to go down from A to D. Or it has to go from the key of C down to the key of F. Well, where we’re starting is it goes from the key of C down to A flat, and then you have to play it back in the key of A flat onto the DAT at 48K, and then transfer from the DAT back to the Alesis ADAT machine, running at its fastest speed again so that you can drop it down from A flat down to F major. This discussion is presupposing you know a little bit about music.

Dave: Yeah. Your musical background is showing through here.

Stan: Yeah, yeah. It’s a rather cumbersome way to do things, but the results speak clean and clear. Part and parcel of my whole reason for all of this is that it serves the needs of the music really well. My background is such that I’ve been involved in music really since I was ten years old, and I turned sixty two last week, so I think it’s fair to say that this endeavor, this mission, is my product. I had a stroke in ‘92 and God gave me another chance and I feel firmly that was ‘cause He said, "Hey, you’re supposed to be makin’ some more music out there. Get with it, ding bat!" I think this is part of that extended endeavor. The goal here is to take a digital original, and it may not be an especially good digital original, but the goal is to make the best damn phonograph record possible out of it, and not just for people who have a VPI TNT turntable!

These records are what I’m cutting now, and they are being played by DJ’s who synchronize them. They play maybe three or four turntables together and synchronize the chords and the beat on ‘em. And they, fsst, fsst, fsst, fsst, jiggle ‘em back and forth. They do their "scratching" on ‘em and so forth and the record that they’re working with has to be rugged. It has to sound good, or they just won’t come back. And so, in an effort to get the clarity of sound, I have no high frequency compressors or limiters or filters. To realize the purity of the system that Keith built into it, it is necessary that I cut at less than real time to get the most onto the lacquer that is possible and, at the same time, not threaten the cutterhead with extinction.

Dave: Is this the first time you’ve had your own self-contained business in your own space?

Stan: Oh God, yes. It’s the first time I’ve had my own self-contained mastering facility.

Dave: So, you can take both analog and digital sources here.

Stan: Yeah, I can take any source. I can take a live broadcast of a presidential speech or somebody saying, "Yesterday, on a day of infamy that will live forever...."

There is one pair of inputs and you can treat the signal the way you want to. Then it goes to the summing amp which gives two lefts and two rights, and then through the digital delay device, which feeds the cutter system. The digital delay is a Yamaha, Model 50k, 20 bit. The other pair at left and right feed the preview So you could do that real time, plug the bass in and do it real time and we could get preview, if we wish.

Dave: We were talking about that fact that you have perfect pitch and it could be both a blessing and a curse.

Stan: Absolutely, when doing this variable speed stuff it’s not exactly a perfect fit. Like from C down to F. C down to F is about six cents sharp and that’s strictly based on the relationship between 33 1/3 and 22 1/2 and 45, you see. Some people wonder, "Well, how do you divide 33 1/3, how do you deal with 33 1/3 and 22 1/2?" Well, 33 1/3 is 33 2/6 and the other one is 22 3/6. So if you do it long division wise, you can work it out with no repeating decimals. You try to round it off and do it on a calculator, you just come out with a string of repeating crap that you don’t wanna see. But, yeah, the perfect pitch thing can be a blessing or a curse in a way. By the way, the interval between two adjacent musical pitches, such as C and C#, is divided into 100 equal parts, called "cents". As one can see, a tone 6 cents sharp is also 6% sharp as well.

There’s 3 strobes on the rim of the turntable-flywheel. Now one of the neat things about this Panasonic SP-02 quartz- lock, five speed motor is you can vary each speed plus or minus 9.9%. So, no 78’s are recorded at 78. Some are eighty, some are eighty-two, most are 78.26 rpm. These kinds of things are important if you’re transcribing early so- called 78’s. You want to be accurate to the pitch standard because prior to 1935, International A wasn’t 440 vibrations per second, it was 435. On a piano, that’s the "A" 6 white keys higher than "Middle C" So, if you want to do a really good transcription from 78s, then you must have a quartz lock variable-speed table that’ll do it.

Dave: Stan, can you tell us a little bit about the console here and the oscilloscope?

Stan: This console is also like the amplifier over there that Keith built. It is entirely home made, hand made, and runs off of two separate power supplies. The monitor circuit and the preview circuit run off of one power supply, and the program circuit, that is, the amplifier circuitry that handles the signal to the cutterhead, is on its own power supply, and it will go to +40 before it clips. So, lookin’ down in here (inside the console, with the top cover removed) it appears like there’s not a lotta stuff in here but there’s everything it needs to be absolutely exquisite and very transparent. This is the meter board, and these are the driver amplifiers for the meters. This is the program amplifier here and these are the preview and monitoring amplifiers here.

Keith built this when he and Tam and I were doing mastering on this lathe for Reference Recordings. This was built somewhere between six and ten years ago. He had to learn about the really intricate details of cutterheads and how flaky they really are, compared with microphone diaphragms, and even loudspeakers. Cutterheads are really bizarre, and their resonant frequencies tend to drift. Well, so do speakers. But you know, you look in there and a non-circuit person, like me, would say, "Well, it doesn’t look like there’s an awful lot there". But on the other hand, I know that there’s everything there that had to be there, because it sounds magnificent. Just absolutely gorgeous. Those LPs that you’ve heard of Reference Recordings, I think especially of the Pomp and Pipes, geez, ya know, and I didn’t get to cut that! Paul Stubblebine cut that on this system.

It’s important to note that when Keith built it, this was only part of the system, because the whole system incorporated his one-of-a-kind analog tape machine as well. The characteristics of the cutter amplifiers and all that were chosen to complement the output characteristics of his tape machine, because Keith is a very astute total-systems type of person.

His tape machine uses very little record equalization and therefore very little playback equalization, so the group delay characteristics are very, very good. And this cutting system was designed to preserve the signal integrity all the way to the cutter stylus. So, I had no idea what the output power of the main system was until I called Keith. I moved this equipment down to Ridgecrest around the 16th of June. Some time after that I called him and asked what the max output level was. He said, "?????, plus 40 dB in the main driver amps before it craps out." And I thought, "Boy, that’s got balls !"

As I say, it’s got its own stand-alone power supply. There’s two power supplies in that box, just for the console. One power supply does the monitoring and the preview. They’re critical but they’re ... "critical" is none too strong a word to use for them compared to the signal purity that you have to have for the main, what we call the program signal. That’s where you’ve gotta have purity to the max. All the stuff, for instance, in the Spectral amplifiers that make them famous for their absolute clarity is the same circuitry that’s built into this console and is built into that driver amp and feedback device up there.

Dave: What are these tanks of compressed gas?

Stan: One is dry nitrogen for blowing dust and stuff off the lacquer before I cut anything. And the other one is helium for cooling the cutterhead. There are small channels inside the magnet structure. You push the helium in and that helps to carry the heat out. That’s a really important part of the cutterhead design, so you don’t want to operate the cutterhead without it.

Dave: So your business now basically consists of taking digital masters and mastering those onto LP. I see a source for analog as well.

Stan: The big Scully 270 logging transport... This machine does take, as you see, fourteen inch reels. This happens to be a half-inch two track that’s on here right now. These amplifiers are a couple of the old original JVC amplifiers I worked from years ago when we first started doing the Mobile Fidelity stuff. Those early things are recorded through these amplifiers. They’re okay, but they’re nothing outstanding, and I’d really like to get some outstanding playback amplifiers before I start inviting audiophile-type people over here. There are cases of records which are high on a lot of collectors’ lists which were recorded on less than what you’d call state-of-the-art or top-notch stuff and I think most of the time it has also to do with the skill of the user, in terms of getting the utmost out of the piece of equipment that he’s using.

Now, what’s interesting about the way this cutting system is set up is that I could do direct to disk with preview, because one of the integral parts of it is this digital delay unit which is 50 kilohertz, 20-bit sampling made by Yamaha. It has adjustable delay, in stereo, of up to 5 secs, adjustable to the 100th of a millisecond. The lathe requires a 1200 millisecond delay for doing a 45 cut at 33. This is in addition to the delay built into the Compudisk computer itself. That’s the 0.741 speed thing I was talking about. The 33 done at 22 1/2, that’s 0.675 ratio, which requires a 1600 millisecond delay from the Yamaha. So, the different ratios have different degrees of speed change on this Alesis machine. And as it says here, on my cheat-sheet, if I want to cut a 33 1/3 at 22 1/2, I go to -180 cents. That’s the pitch-change designation. I go to -16 cents if I want to cut the 45 at 33. You get to the point where you get the timing just right and then figure out what it is and lock it in the memory. It take 1900 milliseconds to do 16 2/3 half-speed mastering of a 33 1/3 disk.

Dave: We heard some quite amazing playback today, direct from your lathe. The lathe has to be totally isolated from the rest of the world, right?

Stan: Around here, seismic events, such as earthquakes and sonic booms, are relatively common. The Earth is always moving, but the most prevalent and troublesome kind is man-made ground vibrations such as traffic. You know, on many of the old recordings, and many of the not-so-old recordings, that are made in New York or Boston or anywhere with a subway system, you can hear those noises. The recording engineers often had to stop the recordings and start later and splice all these takes together. And you hear the subway starting up and then, Whoop, it just disappeared, man! Ya know, when I was a kid I used to wonder, "How’d they do that?" ...until I found out about analog tape and razor blades...

Stan Blows a Gasket, er, Cutterhead

Dave: The most delicate piece of equipment in the whole operation is the cutterhead.

Stan: Yes. And the main reason for the cutterhead being at risk is the high frequency boost of the RIAA equalization. I’ve said it many times, and I know people have heard it discussed many times, but they don’t really consider how much treble boost there is on a phonograph record. I mean, you’re talking, just at 10K, the treble is up 13 3/4 dB, and the boost doesn’t flat-top after that. It just keeps on goin’ up. So if you get some client’s DAT with a some sweep oscillator or something like that, playing games on some of these digital recordings, and you’ve got "0" full scale output at 18 kilohertz, I mean, Snappo, there goes the cutterhead right then and there. What can I say? You’re just off the air then. It’s absolutely imperative to play all the program all the way through before cutting—no skipping around here and there.

Dave: In the space business, That’s what we call a "single point failure." If your cutterhead goes and these two guys in Germany are no longer around, what the heck do you do?

Stan: Well, yeah. And when I first was setting this system up I had the SX 68 cutterhead on the lathe, with the Scully tape playback machine at the input-end of the system. While I had it set up, one of those tape machine electronics decided to go noisy - static/static - and it fried one of the channels in that cutterhead. So I was off the air with it, and then in calling around I talked to my friend, Richard Simpson, down in Hollywood. He had an SX 68 cutterhead with the opposite channel fried. So we got together and I’ll show you what came out of it.

I don’t think this has been done here in the States. I don’t think anybody here in the States has had the courage; everybody’s been scared of these cutterheads. Nobody wanted to take ‘em apart. And so, when I fried the thing, I thought, "Well, okay, I might as well bite the bullet. The thing’s no good the way it is if it’s got one channel dead." So I thought, "Okay, well, I’m just gonna figure out how to take this damn thing apart."

So I sat and I really studied it for awhile. I’d studied these things for many years, and then finally figured how to get it all apart. These two entirely separate magnetic structures are bolted on a nonmagnetic frame. This is a magnet structure, and there’s two voice coil assemblies inside; a tiny feedback coil, and a much larger drive coil. This silver colored metal frame is not magnetic. So you unbolt this section here. You loosen the back plate, and you take this part off the top, which comes off by screws after you take this plug off. And you wind up with two entirely separate structures which have the coils inside.

Picture this. Picture a funnel, okay, a funnel whose sides just expand a bit and then become parallel. I remember some old fashioned funnels which were used to change oil in engines, and the sides went up, like a coffee can welded on, or soldered on the end of the funnel, ya know. That’s what’s inside here. You have, in fact, a voice coil former that’s shaped like a funnel. So the sides flare out and then they go up and become parallel, like a spool of thread, with no thread wound upon it. And on this parallel part was wound this wire which I unwound off the drive-coil former, and it is seven feet long. And it appeared to be, when I measured it under the microscope, 5 thousandths, rectangular cross- section aluminum wire. This coil is the drive coil, the one which burns out or self-destructs from heat and vibration as it’s the one connected to the amplifier output terminals!

Now, the "funnel" on which this wire is wrapped comes down to what we might call "the spout," the skinny end, but it’s solid. At this location is wound the feedback coil, operating in its own magnetic field supplied by this separate ring magnet. Then the push rods skinny down even more to these pieces of metal here which are smaller gauge than even the small wire of a paper clip. The end of that armature has an "X" slot milled in it. In the center where the two slots cross, is a milled out circular area. You see that?

Dave: Yes.

Stan: Okay. Now, what happens is, those push rods from the two coil assemblies come up and they do this. Each push-rod wire is bent exactly 90 degrees. They come and they go in, and then they come back out, like that. Each push rod comes out, and it looks like they’re crossing on the end of that armature. But in reality, they’re not. And the trick was how to get those off of there. Well, it turns out that it’s epoxy resin that holds those push rods into that armature. And I found that if I was patient and used methyl ethyl ketone (MEK), and just sat here and put one drop of MEK on the end of that armature, and then scraped it with a razor blade, I could get the old epoxy dissolved and removed. And I was finally able to get all the epoxy out and then those push rod ends, those links, just popped right out of the armature. And then I could get the whole magnet structures apart.

So I did this on this one of mine, serial 289, and I did the same thing on Richard’s SX 68 and his model, let’s see, this is serial no. 24. It’s a real early one. But one channel was real good and the opposite channel was good on mine so we cross-multiplied the parts and I got ‘em all back together, and mixed up a little bit of epoxy, got a real good mix on it, and just one tiny drop off the end of a toothpick was just what sat right on the end of that. And this thing works great.

It works really great. And I don’t know of anybody who’s had the courage in the States here, to take a Neumann cutterhead apart. So I can repair it, if somebody has two burned out cutterheads where the opposite sides were burned out, as we had here. As long as we have exactly the same model number, then I could do that. If two different folks own each of the heads, then those guys are gonna have to resolve who the hell owns the functional cutter. That’s a different story, but with that kind of repair I can fix ‘em.

Dave: Well that’s awfully amazing. So we’re talkin’ to the only man on this continent brave enough to repair...

Stan: Or stupid enough to admit it! (Laughs) Yeah, to take a Neumann cutterhead apart, and actually get it back together, so it worked.

Dave: Something you also said you’d like to do is to try to take the Samarium Cobalt magnets off of the Neumann cutterhead and engineer some modern Neodymium magnets for those. Sounds like an interesting task.

Stan: Yeah. Interesting and expensive, I presume. Anything that’s good like that is bound to be expensive—gettin’ people tooled up to make that kinda stuff. I have no idea what’s involved. I know magnet technology has improved big time over the years. I mean if we’re to stay with the small package like that cutter. There’s nothing that says that it has to be that small. It’s gotta stay in a package that will allow the parameters of the cutterhead suspension box to deal with it. You can mount a Westrex on that cutterhead suspension box, but it’s quite a chore and it’s not too satisfactory. That’s what Keysor-Century had in the earlier stereo days.

I haven’t seen Bernie’s latest setup, so I don’t know what he uses for a cutterhead suspension. I know he has fully automated variable pitch and depth, of course, and I don’t know how he achieves it with the Haeco cutterhead. The Haecos, like the Westrexes, are very heavy and that poses a different set of problems, trying to do what we call here on this Neumann a "floating" cutterhead. I mean, that cutterhead just floats over the lacquer, doesn’t touch the lacquer at all, except for the stylus.

The Westrex cutterhead had a small arm that came down with a jewel on the bottom of it, and the jewel rode on the disk, a few turns of the lacquer ahead of the stylus, and alongside the stylus. Actually rode on the un-cut part of the disk. It was called an Advance Ball. And the weight of the cutterhead was mostly offset by a stout spring. There was just enough downward force to allow this advance ball just to glide over the surface of the lacquer and you could set it up so that if you wanted to cut a three mil groove you adjusted the vernier threaded shaft on this advance ball and it raised and lowered the cutting head the required amount. But it’s very hard to get good variable depth using an advance ball system. Used to have to run DC bias through the drive coils, push em down harder. Not good. Makes audio non-linear as hell!

Woofer Madness

Dave: Your monitoring system here just sounds phenomenal. It’s awfully nice.

Stan: Thank you very much. Totally home made. Notice that the mid range drivers and the treble drivers have absolutely no enclosures at all.

Dave: The treble drivers are supported by these beautiful little wooden stools. Those appear to be plastic milk crates?