You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback

ISSUE

23

january/february

Recording the

Michael Green Way - The S.U.N.Y. Studio

by Sasha

Matson

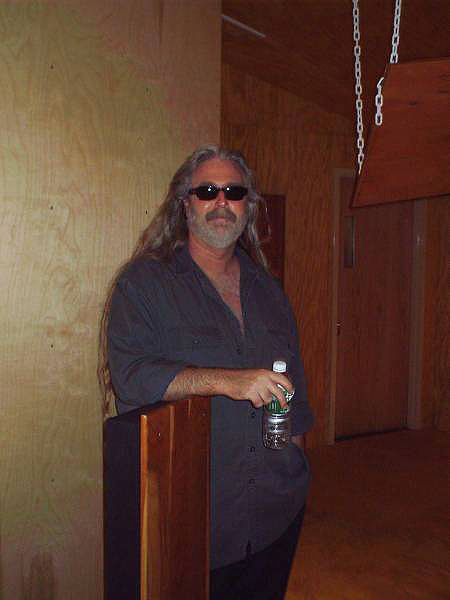

Michael Green Surveys the Studio

On a per capita basis, there is a small high-end audio convergence occurring in Otsego County, deep in up-state New York. In addition to my own efforts, there is my buddy Art Dudley in Cherry Valley laboring over articles for Stereophile. And in a complete coincidence, the involvement of audio guru Michael Green with the State University of New York, College at Oneonta, where I am a member of the music faculty.

Around the time I arrived in these parts in 2000, Michael Green was asked by Dr. Robert Barstow, Chair of the Music Department at SUNY Oneonta, to design a new recording studio to serve the growing Music Industry program. Like many institutions of higher education, the music curriculum has become more varied in recent years. In fact, the Music Industry major offered here is one of the more established in the country, now serving over six hundred students.

A three-semester sequence in "Audio Arts" is offered; two full-time faculty members are involved with that, and with the operation of the recording studio. What makes this program unique and of interest to readers of Positive Feedback is that the studio employed in this academic setting has been designed from the ground up by Michael Green, of Michael Green Audio.

I first became aware of Michael's work through Positive Feedback, way back when it was still a print journal. Michael Green graced the cover of Vol. 7, No.3. That issue featured an extended group PF editor/writer conversation with Michael, which I recommend if you can get your hands on it. (That issue is available as a back order on the PFO website. You can also go to Michael's extensive website where that article is posted at: www.michaelgreenaudio.com)

Central to Michael Green's philosophy is a pro-active view of the importance of "tuning", of being in "tune." In one article my Michael posted on his website titled "Inside the Tune - The Tunable Recording Studio" he summarizes this paradigm:

"We have all heard musical notes displayed, with such mastery from the world's greatest performers, that they almost seem suspended with their own identity. This is the magic of music. It is the inner weaving of these musical notes, moved with emotion, to form meaning. This meaning is controlled by a particular function called "tuning." No sound uttered can live in harmony, on a consistent basis, without this function."

Thanks to that issue of Positive Feedback, I encountered for the first time terms like "tuning," "room tuning," "room correction," and related concepts. I recall thinking that the idea of focusing on the entire aural environment present during music recording and reproduction, was a relatively new meta-concept for the high-end audio world to grasp. Michael Green of course had been involved with high-end audio for many years prior to this, as a designer of all sorts of hardware; racks, speakers, cables, etc. As his philosophy and technical solutions evolved, Michael began building hardware devices dedicated to addressing sonic issues related to the total listening experience; tuning the room itself, both in the home, and in the recording studio. All the hardware products currently offered by Michael Green Audio are tunable as far as I know.

It wasn't until the recording studio at SUNY was framed in, and construction was almost complete, that I put two and two together and found out that it was a Michael Green design. So I have been happy to see Michael here in these parts recently, as that studio has come together. I have recorded my own musical projects in the SUNY Studio, many student bands from SUNY that I also have directed, and have heard other artists record in that studio as well. This past August, the young pianist Fernando Landeros recorded a self-titled album of solo piano repertoire in the SUNY Studio, which has now been released on the Forte label. (Go to www.forte-arts.com for specifics, and to order). I refer you as well in this issue of Positive Feedback, to my related album review of the actual album repertoire, performance, and sonics.

When I found out that Michael Green would be visiting the SUNY Studio to assist with preparations for the Fernando Landeros recording, I made a point of visiting. I was there on the first day of recording, after the room had been set up, or tuned, as Michael would say. This project involved a collaboration between Michael Green and Paul Geluso, who engineered the recording and is a member of the SUNY music faculty. Paul is an experienced audio engineer and a creative sound artist. I interviewed both Michael and Paul about their specific roles in the current recording, as well as getting their further thoughts on matters related to music recording in the context of high-end audio. I include those conversations separately in the Interviews section of this issue of Positive Feedback Online.

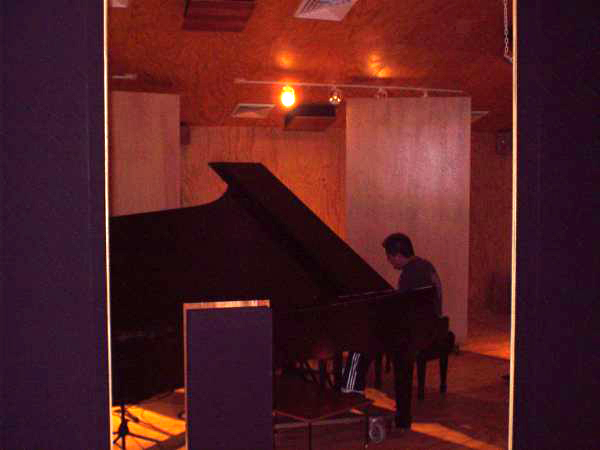

The first thing I noticed when I walked into the SUNY Studio on the first day of recording, was that Michael had arranged his large standing 'PZC' devices in an ellipse surrounding the Steinway Model D being used for the recording. These tall 'PZC' (short for "Pressure Zone Controller") devices have two differing surfaces. One side is hardwood, and the other is covered with a cloth felt-like material with a layer of air behind it. Michael Green could describe this more exactly, but they seem to my eyes like large shallow boxes stood on their ends. What was striking to me initially was that the wood surfaces were facing inwards, towards the piano and the microphone array. This created a highly reflective sonic situation—and this was the desired result. Paul Geluso had created a 'three zone' mic'ing of the piano—one pair physically inside the piano, the next further away but still within the ring of PZC's, and a third mike pair positioned further out into the studio room. The final recording was meant to provide a composite of these three audio perspectives if desired. What would work best as a final recorded result was dependent on both the engineer, (in this case Paul Geluso), and the tuning conducted by Michael Green in preparing the room, as well as the placement of the piano and the stand-alone tuning devices.

The Steinway with microphones and PZCs

As Michael described it, "…the most fun for me was actually showing Dr. Barstow how the room worked while he was playing before the recording started. He could actually feel the keys get lighter or heavier to strike as I was tuning. This is the key to it all. This room is not something to kill, but instead is something to be part of the music event."

As a composer, I have noticed historically that some composers and musicians are better than others at describing what it is they do. There is no pattern that can be detected between the quality of the music created by a particular artist, and their ability to analyze and express verbally what goes into that art. On the upper end, for example, would be someone like Stravinsky whose Poetics of Music lectures remains a gold standard. Also high up there in my book would have to be Leonard Bernstein's Unanswered Question essays- also interestingly enough, lectures in an academic setting.

I put Michael Green in a category with a select group of other high-end audio designers, whose analysis about what they do, is an integral part of the design work itself. People like Bill Low, CEO and Designer for AudioQuest, or Dennis Had, ditto for Cary Audio. There are others, but perhaps not that many. I admire very much people who bring creative intensity to their work in high-end audio, and a cohesive philosophy to back it up.

For someone like myself, who is definitely not an audio designer, this raises certain issues. When I had the pleasure of interviewing Bill Low of AudioQuest recently for Positive Feedback, Bill touched on this when he said, "…the reviewing community, people who aren't actually going to go design and manufacture the product, in many ways are better off turning off their brains and just listening." I can understand what Bill Low is getting at here, and that may include a feeling of frustration when a creative person or designer feels that they are being misunderstood. On the other hand, there are certain things that critics and writers can contribute to any dialogue—and I think they should try to do so.

First of all, most competent writers bring objectivity that, de facto, the creator in question lacks. When it's 'your baby,' objectivity is sometimes hard to come by. Secondly, enthusiasm from commentators can, and does, encourage artists to continue growing and doing what it is they do. Thirdly, reviewers are also, de facto, part of a chain of communication that is necessary, to avoid the fate of worthy art and crafts that might be of real interest to people, 'dying on the vine'—overlooked in the hubbub of modern consumer culture. Fourthly, there is a genuine educational role that writers can play if their intentions are good and they have some information and insights to communicate. There may be other reasons to write for Positive Feedback Online, but let's not get carried away with ourselves!

In my opinion, there are reasons to both understand an artist or craftsperson's original intent and explanations, and to supplement and gain added insight from others, in addition to those primary sources. It is valid, for example, for a writer of the caliber of a Charles Rosen to explicate what a Beethoven Sonata is about, and how it is constructed, because Beethoven himself will not give us a lot of help in that regard- at least not verbal help.

When a person with original and new ideas comes forth, and presents those to the world at large, they are sometimes in the frustrating position of encountering people who don't have the faintest idea of what they are talking about. In such cases it can be productive for another person to come along and simply say: "Hey, this thing is of interest, and is something that you should pay attention to."

Michael Green has not only developed some unique concepts about audio and music, but also terminology to describe these things. In order to try and get a handle on what Michael is saying, you can go to his website and read his articles for yourself, at: www.michaelgreenaudio.com In reading through what Michael has presented there, it strikes me that it might be helpful to try and summarize, in his own words, some of the history and thinking that has led him to his current audio design work. Then, one is in a better position to appreciate the designs that went into a project like the SUNY Studio, and how that affects the recording process itself. On Michael Green's website he has posted an article titled "The History of Acoustics." Among the concepts Michael touches on is the historical development of recording studios:

"This was a room specifically designed to play an instrument and have them picked up by a microphone. These rooms opened the door for different acoustical theories... One well known theory was called the "Dead" theory. The "Dead" theory was built on the premise that the walls of the room should not participate in the sound at all… thus giving the word anechoic—meaning no echo or no audible return…(later) a new theory was adopted. This theory was called "Live End, Dead End." The engineer's job was to then determine in what proportion, from "dead" to "live," in which he wished to do his testing or recording… recording studios began experimenting with different shapes of reflection versus absorption… Stand alone and retrofit acoustical products were now developed… There were products developed to "trap" acoustical space, to diffuse acoustical energy, to resonate acoustical energy, and to absorb acoustical energy…The "trapping" theory believed that if you trap the basic fundamental nodes of any given room…you could equalize the room and maintain "flat."…The opposing side was a diffusion system. This diffusion system was designed to allow frequencies to find their particular tonal spot or resonance on the diffusion panel, and therefore diffuse their counterpart nodes (peaks) in the room… In 1988 a new method was designed. This was the method of "acoustical barricading." The idea was to build a room with as much energy as possible… and then place barricade products in strategic places to control the room. This method was called "Pressure Zone Controlling."… The pressure zone control theory was based on the idea that sound, as all energy, travels in spherical patterns. Therefore sound should be controlled from more of an aerodynamic approach, as opposed to a 'beam' approach."

Michael Green concludes this summary with a brief description of the current concepts that he has applied to designs employed in the SUNY Studio, and to many other projects and products Michael Green Audio is involved with:

"The next stage evolving from "Pressure Zoning" is "Variable Pressure Zone Control." By placing materials, built like musical instruments, to variably tune the entire audible frequency range, and placing them in strategic pressure zone areas, you can now variably control the sound of the pressure zone. The next step is building the wall (again, like a musical instrument) with variably controllable devices built into the wall to not only gain control of the acoustics, (i.e., laminar flow and horn loading of the room), but also now the mechanics of the room."

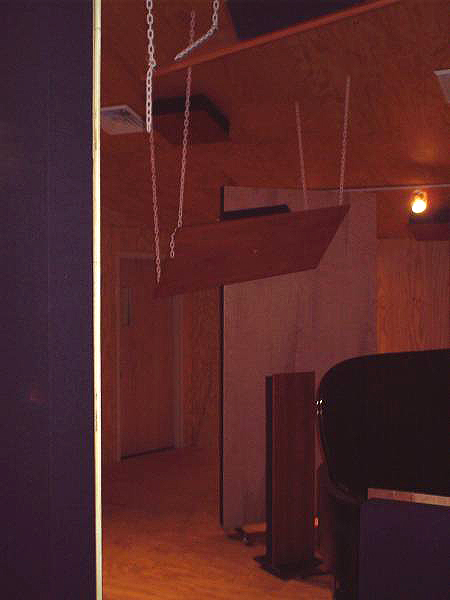

Close-up of a Cloud

The terms Michael Green uses in his studio designs are a combination of standard terminology, and his own personal labels and product designations. "Clouds" refer to acoustical panels suspended from the ceiling, and Michael has built a number of what are commonly known by the acronym 'PZCs', in various sizes and formats that are currently installed in the SUNY Studio. Michael also refers to "halos" in describing the behavior of sound and it's component harmonics. At the piano recording session I photographed the recording set-up, and you can clearly see the Clouds dangling down from the ceiling, and an array of large vertical PZCs that can be rolled around, and are surrounding the piano itself in an elliptical arrangement. Mounted on the walls and ceiling areas of the studio are various sizes of fixed PZC boxes that contribute to the overall sonic design of the studio. The walls themselves are built or installed in segments that can be tuned through adjusting brass disks that protrude from the surface of the wood panels used.

Steinway with PZCs and Clouds

Tuning a room designed with Variable Pressure Zone Control devices utilized both as stand-alones, and integral to the construction of the walls, ceilings, and floors, can potentially yield a sonic environment that is flexible and musical. These objective sonic goals finally yield however, to subjective evaluations- what works, and what does not? What is appropriate for one kind of musical project may not be for another. And this ability to adapt is a definite design priority. What is in tune for one person or musical event may not be in tune for another artist or type of music. The idea of an infinitely flexible and adjustable studio is not in and of itself new, but I think that Michael Green's diligence in striving towards that elusive goal is worthy and of interest, and he's gone further with that than most sound designers out there. Would this type of ideal studio replace recording music in concert halls, or other existing varied venues known for their unique acoustics? Of course not, but in an academic setting where students are meant to confront a wide variety of differing ensembles and recording techniques, and flexibility is needed quickly and often, then a tunable studio has obvious practical applications.

In practice, in the real world, (or in an academic state-funded setting), there are always choices and compromises involved. 'Cost no object' is nice to read about in a Michael Fremer turntable review, but it is rarely, if ever, going to occur in any facility of the State University of New York. As Michael indicated when I interviewed him regarding the studio designs, significant barriers to new ways of thinking are encountered when one comes up against the bureaucracy. In this case, state fire codes prohibited using the kind of wood materials for the walls and floors of the studio that were originally intended. This compromised the acoustical results of the designs, and according to my recent conversations with Michael, only now are those plywood floors and walls that were actually installed, instead of the specified hardwoods, starting to become tunable—four years later!

Fernando Landeros at the Steinway with PZCs

Another article Michael Green has posted on his website is titled "The 'Simplicity' of Sound Reproduction." Several key ideas popped out at me on reading this, that indicate a certain aesthetic approach. As Michael puts it:

"…everything in the universe consists of atoms whose subatomic components are constantly in a state of flux… we do not want to destroy any portion of the original mechanical vibration through absorption because we do not want to destroy or take away any of the harmonics of the original fundamental tone… The goal of audio reproduction should be to reproduce, in the final format to the listener, the original sound with all its associated harmonic structure intact."

What is being expressed here is a value system that places a positive aesthetic emphasis on the preservation and enhancement of the reproduction of the harmonic series present in music. I agree with this objective in terms of high-end audio, as I think others would as well—Sam Tellig, of Stereophile, often speaks of this kind of ability to reproduce harmonics in a life-like manner, as a positive when evaluating high-end audio hardware. Designers like Dennis Had of Cary Audio I think also share similar conceptual goals—and I know his designs well, having reviewed a number of them for Positive Feedback Online. Currently all the electronics in my 'A' system are Cary Audio products, and largely for this reason!

There are always alternate ways of looking at something however. A particularly insightful quote I often mention to my students, is a remark made in an interview by Brian Wilson, (yes, the great songwriter/composer of the Beach Boys). When Brian was asked about the current state of popular music, he stated, (and I summarize), that he felt that popular music had been killed by the invention of electric guitar tuners. What Wilson is referring to, for those of you not around electric guitar players a lot, like I am at SUNY, are those little digital boxes that guitarists can plug into and put their instruments quickly into perfect tune with either digital numbers or a meter. On the positive side, this avoids the twenty-minute long tuning sessions made famous by the Grateful Dead in their heyday—and I remember those show-stopping moments. But what Brian Wilson is getting at, is that when all the harmonics in an ensemble, or in a piece of music that gets recorded, are perfectly aligned, that are in fact literally in tune, then the music becomes dead-on-arrival! This is because when all harmonics are perfectly matched or aligned it is possible to lose the inherent infinite complexity and variety that is present in acoustic instruments and voices—in nature. This is something that designers of electronic instruments such as synthesizers have wrestled with for years now. Nature is complex. Electronically generated in-tune sine waves are not. I think that this explains a lot of the emotional disconnect many listeners feel with contemporary mass-market pop music; not only is it compressed and limited up the wazoo, but it is so tuned that all harmonic variety and life is bled out of it, creating a very sterile result. Compare most any recent recording off a commercial radio station today, to a Phil Spector recording from the early 60s, or the Beach Boys for that matter, and you can hear immediately the phenomenon that Brian Wilson is talking about, and that audiophiles intuitively seek to overcome.

The advent of recording software as powerful as the now-ubiquitous ProTools program, or others like it, has only increased the natural tendency of artists and their producers to hanker after audio perfection. I know this first-hand, having recently recorded a vocal demo in the Michael Green-designed SUNY Studio. On that recording there was a particular vocalist in the group whose intonation was egregiously out of tune, certainly enough to preclude any positive use of that particular demo. So what did I do with Paul Geluso who engineered that recording for me? We went into the tracks, and with the software, literally re-tuned almost every note that horribly flat singer had sung. Nobody would ever know this, unless they were told. So be careful what you ask for!

"Tuning" may be a productive positive aesthetic when applied to high-end audio gear and listening environments, but the idea itself is open to varying interpretations. I have the feeling that Michael Green has used this word and concept so often in his efforts to explain himself over the years, that the word "tune" has become somewhat amorphous and stripped of precise meaning. Michael speaks of "The Tune", and refers to "Tuneland" on his website. Such a loaded term risks becoming a tautology, if used in a vague and nebulous manner- rather than representing a coherent comprehensible idea, that does indeed point us towards what is desirable in music performance, reproduction, and the listening environment.

At a certain point a concept as all-inclusive as The Tune seems to me to verge on a mystical, even spiritual view of the universe. I myself look at elements of music in that manner- this may or may not be your particular cup of tea. However, one can choose to follow such a conception up to a certain point and no further, and still yield practical positive results.

I followed up on my initial interview with Michael Green regarding the SUNY Studio project, and Michael was kind enough to respond in writing to some of these questions. I asked him to comment on the difference between his original design conceptions versus what actually got built. Michael answered that:

"In any studio, no matter what design, it is you who must learn how the fundamental design is intended (to be used). A Tunable Studio is designed not to be in any particular camp of design but more as a tool that allows one to go anywhere, in one's imagination, to get the job done… It is like I said, one big giant instrument waiting to be tuned into action. To use this type of studio, you must first learn how to "play" the studio itself. We build several Tunable rooms a year now, and at first, it is a shock to the user because for the first time, they realize how much music can really be produced instead of killing the harmonics of the piece, which is what is typically done."

It is to the credit of the Music Department of the State University of New York, College at Oneonta, and to the support and advocacy by Dr. Robert Barstow of Michael Green's design concepts, that a Tunable Studio now exists for the many interested students in the Music Industry program. Some of these students will encounter for the first time in that studio, what it means to experience music recording at a very high artistic and technical level. In the future I hope to achieve the creation of a dedicated Critical Listening Room that will augment the student's experience of the complete chain of high-end audio music-making and re-creation. This in turn can achieve Positive Feedback in the musical lives and future careers of our students- and help to constructively address the growing debates about the future of high-end audio in a productive manner.

Stay tuned!

L. to R: Vadim Ghin, Dr. Robert Barstow, Paul Geluso, Michael Green, Elias Guzman, and Fernando Landeros in the SUNY Studio