You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 2

august/september 2002

An Interview with Winston Ma of

First Impression Music

by Rick Gardner and David W. Robinson

(All photography and image processing by David W. Robinson.)

Following is part two of our interview with First Impression Music’s Winston Ma. Part I of that interview appeared in PF Online, Issue 1.

Winston Ma beside the pool and garden outside his listening

room

Ma: I also spoke with some trained engineers. I found that they always went back to designing and building studios, and I had to tell them, "Look, listening (to music) in a studio is entirely different than listening in an audiophile listening room!" (To put it most simply,) this is because in a studio certain places should be very dry, so that you can hear the music clearly; then you can add something to the sound to produce (what you’re looking for.) But in the music room, you have the reproduction of that recording. I think that it’s wrong for some engineers to build a listening room for some rich guy using the concert hall concept. The characteristic parameters are all wrong, and the listener will be deprived.

I think that the listening room should be very neutral, where you get what you hear, instead of treating your listening room like a concert hall with a two seconds of reverberation or whatever. That’s wrong; that’s how I feel.

(Chuckles all around the table)

Robinson: A concert hall on top of a concert hall!

Ma: Yes. And this has been argued about many times. I visited many homes, and when I moved here—I bought this house in 1989—I had good friends like George Cardas and others listen to my system. We came to the conclusion that it was not adequate in the room where it was, so I decided that I needed to build a music room. This was the beginning of my exploration of how to build the perfect music room. There were lots of ideas; fantastic ideas!

(I had to) judge based on the advice of lots of people, plus my own personal experience. It’s better to be safe than sorry when doing work like this. It doesn’t matter if you’re spending a million dollars or not; the pain of tearing out a newly built room is very significant, and you need to know what you are doing before taking such a step.

At this point, Winston, Rick and I took a break and moved out doors to Winston’s striking garden area for further conversation.

Robinson: We had been talking about your background in audio, and how you became interested in listening rooms. When were you actually able to begin designing a room?

Ma: As I said before, this took a very long period of time. It began when I was in my late 20’s, when I first started to become more interested in my equipment reviews, and, obviously, there was a need for a better listening environment. Because of the constraints of the available space living in Hong Kong, the number of family rooms, we couldn’t do much about it. So, I have been dreaming about my own music room ever since.

Over the years, I have been to many customers’ homes; some of them have been good enough, some of them were so-so. Some of them had very spacious rooms, but the space was wasted because the placement of the equipment or the arrangement of the listening area is such that it didn’t work out well. But I did not readily express my opinion, because we have to respect personal preference. On the other hand, over the years I have helped some people to build listening rooms and have personally designed a number of listening rooms in our show rooms. Some may have not been ideal, but in the East several of them have been very good. They were remarked on by editors of some magazines and by audiophiles alike as the best in Hong Kong; some felt that they were the best in the Pacific Rim, too.

But if it came right down to it, bottom line, that I would be given a chance to build a listening room for myself, to be used for the rest of my life—well, that’s a serious problem! It’s not as easy as A-B-C, not like building just any listening room, because I wanted to achieve, literally, the perfect condition, which is difficult, because there is no perfection, as such, in this world. How we can come as close to perfection as possible is a matter of very serious thinking and expensive research.

As I said, I had an opportunity to meet with friends right here, at this very house, to start talking about it. Long before this, of course, I had been thinking about what sort of design, what sort of form I should like; but when it came to doing it practically, when it came to the commencement of this planning—the pre-construction period, then we had to consider the various aspects that were listed in the notes that I have given you.

Paul Weitzel, Rick Garder and Winston Ma in Winston’s

listening room

Robinson: So then, by the late ‘80s as you were getting ready to leave Hong Kong, you had already been thinking about this for a long time.

Ma: Yes, by the time that I bought this very house I had already decided that none of the rooms available in the house were suitable for a good music room. And because of the availability of extra land on the lot—I checked with the real estate agent to be sure that I could make an extension here—my mind was set that some day, when the opportunity came, I would build one right here.

Robinson: In this area to the west side of the house.

Ma: There had been lots of considerations and some arguments about this; as a result, I spent some funds on coming off a draft by the architect. But the architect didn’t approve. So I made the good decision of asking the President of the Northwest Audio Society, a true audiophile, to design the room. (So we started to work.)

I’ll give you some options. These may not be meaningful to a reader, but it will give them an insight into the fact that before they make a decision to build a room, they should think thoroughly. You want to avoid regret! You might think, "this is the spot," but you may overlook certain other factors that may become detrimental to the overall goodness of the room.

I had thought about building one by extending the sitting room out there, just like that. (Points to the east.) It’s good, because people can come in and start listening to music. But then the "family factor" comes in, because if you do that to the sitting room, then you block the traffic flow between the family room, the kitchen, the master bedroom, and upstairs. Then the family members can’t move, because the owner (that’s me!) might be having an important meeting, and they wouldn’t be able to walk about. This would create an inconvenience for family members.

So we moved the other way, to the west side of the building, which is kind of sloped. It is an ideal place, because we could excavate some of the earth and build a storage room underneath in the basement, or use the basement as the music room. This is a good idea because then you have a very dead wall, and at the same time a very solid wall. Over there, the whole thing would be exposed to the sun; on the other hand, it would also be close to the septic tank and the drain field. Ah, that may cause trouble!

Finally, I settled on having the room on the north side, with the back of the room facing west, and the front of the room facing east, towards the back door of the family room. In between we put a sunroom. I think that this was the best location, because this was farther away from the traffic at the roadside. This is important, because every truck that passes by produces low frequency rumbles that will shake any solid floor. So this is what we chose.

We think, as Rick said, that you feel comfortable sitting in the room, for reasons unknown. It’s a psychological thing, and I don’t want to waste time in investigating why it is so, but this feels like the strong side. I just like the place, like that! Instead of having it on some other side, or this angle, or that angle—just like that.

Each time we made these changes, our draftsman had to make a change, and it cost money. For a while, we thought that we should have a swimming pool in between; later on we dropped the idea, and I’m glad we did. A swimming pool in between could have created other problems—leaking, or whatever…

Robinson: Humidity…

Ma: Yes, humidity, or also, when people pass the music room it seems to be a barrier instead of a preferred area leading to the music room. So I’m happy that this design is this way.

Robinson: The way that you designed it does provide an anteroom to the music room that helps to prepare you to listen rather than being a barrier. You have privacy without excluding anyone.

Ma: The privacy between two parties, the family and the visiting guest. Guests can come in through the garage, or the main door, or through the back pathway into the garden and the sunroom. These are the sorts of things that you should take into consideration when designing a music room, just in case.

Robinson: It makes you think

carefully about what area, what site, and what portion of a site you should use. I’ve

had two dedicated listening rooms now, and have found that it is a difficult thing to

think through all the factors…

Ma: Yes! It is!

Robinson: … and to try and make it the best you can in the circumstances that you have…

Ma: Yes.

Gardner: One of the things I noticed about the anteroom is that listening rooms are notoriously difficult places in which to socialize; they’re not set up for conversation! And so, being able to move back and forth between those two environments, the dark protective recess of the listening room and then you come out into the anteroom, which is the sunroom, which is very much conducive to sitting and facing each other and socializing, drinking some tea—that adds in interesting ways to the experience.

Ma: True. And visiting guests who have that kind of psychological preparation don’t have to talk much in the listening room. They can leave those kinds of burning questions to be solved later on in the sunroom or the entering room, instead of the listening room becoming a place for chatter.

Robinson: Which happens all too often!

Ma: Yes, all the time! And it spoils the fun of listening. There may be some listeners who want to concentrate on the music, but others keep on commenting, which is very annoying.

Robinson: It’s like many of the audio club meetings that I’ve been to over the years… (general laughter) … where you set up a demonstration, something that you hope will be a worthwhile experience in listening to the music, and half of the crowd may be sitting there chattering away…

Ma: Right, right!

Robinson: As a matter of fact, it’s very rare to find a very happy audiophile group meeting… (general laughter)

Ma: True.

Robinson: But your environment concentrates one’s attention.

Gardner: Then you have the third environment, which is where we are now doing this part of the interview, which is the carefully sculpted garden, which is yet another dimension of the experience.

Ma: Yes.

Robinson: Winston, I’m curious: who helped you actually accomplish this project? By the early ‘90s you had reached the point at which you were doing serious work; who were the key people?

Ma: There were a number of people… very many. Many contributed an idea or two, which I had to think about; at the center of the project, I had to consider whether the ideas were practical or feasible or not. Say, for example, without mentioning names, the roof and the floor—there were so many ideas about how to build the foundation! Some said that it should be wood; of course, wood is wonderful. Some said that it should be slab concrete. Some said that it must be hollow, and de-coupled from mother earth. Some said that there must be some posts underneath, so that you can "tune" the resonance characteristics of the floor, to couple with the walls and all other things.

These are all great ideas; but whether they would work well, and whether they were practical was something that I had to decide. I made the decision to do something that made me very happy, and without reservation recommend this to all audiophiles who are contemplating building a listening room: and that is to have a solid floor.

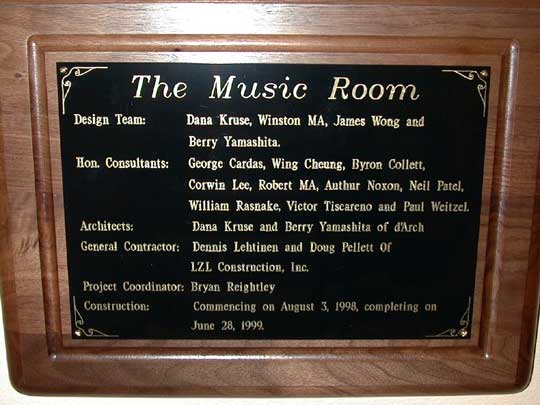

As to the names of some friends who helped—well, there was George Cardas, Neil Patel, William Rasnake, Dana Kruse who kept an eye on (how it looked), and James Wong who is an intelligent and well-trained acoustical expert. There were many others, too; the list cannot be exhaustive!

There was a delay of some five to six years in executing the work, due to the fact that I was very busy during that time doing some other projects, serving as a consultant for some companies, while at the same time running my own company. My time in Seattle was (very limited.) But since 1997 I have been settling down, so I could start the project.

Robinson: So you spent some seven or eight years talking and planning and working up ideas…

Ma: Yes. We started talking as early as 1991.

Robinson: I think that I met you back in 1992, which was shortly after George Cardas and I first met each other (through the kind introduction of Ray Chowkwanyun). You and I first saw each other at George’s house; I remember that you were talking about this idea at the time, and were very interested in his listening room…

Ma: Yes, yes.

Robinson: … and of course George has an outstanding listening room.

Ma: Yes, he has.

Robinson: It’s very different from yours, but very good.

Ma: Yes, the sound is very different, as you said. And so everybody has a preference; as I pointed out, individual human perception plays a most important part in this process.

Robinson: Tell me, Winston, when you were working through this design, what were you looking for? What were your key objectives? What were your priorities as you thought about this?

Ma: Well, the list of priorities was very long, but the first priority is certainly to reproduce music at its best; in other words, to keep or to restore the musicality of the recorded signals. This is the main objective. How to achieve this goal is a question that required a lot of detailed work. I didn’t want to have a spectacularly sized room; I wanted a room of moderate size, a size in which I felt comfortable. Not too small, so that I would feel congested and restricted, and not too big—you would feel lonely, as if you were in a huge prison. Just the right room, one that can produce music. It must also be very quiet and natural. These were the main objectives.

Gardner: At what point in your thoughts did the idea of separating the listening room from the living space with the sunroom, and the relationship of the whole to the garden begin?

Ma: Well, to be honest and avoid exaggeration, it happened as an integral part (of the design work). Gardening is another of my hobbies; I like gardening! So I married the garden and the sunroom to the music room. I consulted a gardening expert; he said that to give myself, or anyone going to the music room, a kind of freedom from constraints and all pressures so that we could enjoy the music, walking in the garden, or sitting in the sunroom would help. And he was right.

Back to your question about objectives: to build a music room in which you can be totally involved and enveloped by music is a very, very difficult thing to do. You can build a very lively room, certainly you are surrounded by the sound, but that’s not what I mean—the sound is a mess! You can have a very detailed and analytical room, one that is very dead and has powerful (electronics and) speakers, but whether this is a musical room is subject to debate. But I would have thought that if you have a group of players playing together homogenously, in terms of acoustics, with that kind of harmonics mingled together to form a whole piece, and if you have the feeling that you are there as well, then this is the consummate level of music reproduction. But this is still a long way from having the same feeling as you get in a live performance.

Like many other people, I have been to live performances. And yet, sometimes, you may find it more enjoyable to be listening to reproduced music in a controlled environment rather than in a concert hall, where you might find some deficiency in getting the result you want.

Robinson: This is something that various members of the Positive Feedback editorial group have talked about. Harvey Rosenberg has discussed it, I’ve talked about it—this idea that audio as an art form, in some ways, can give a more satisfactory, a more involving experience than you can have in many live events.

Ma: Yes! Because in a listening environment, in your music room at home, you and the music are in direct confrontation and contact. A concert hall has a different configuration, and the feeling is different.

Robinson: Very different! Some of the so-called "live music events" are not very satisfactory; the quality of the sound in some concert halls is compromised. And there are some very bad seats in most halls…

Ma: Yes, for example if you go to listen to a jazz group live, you don’t find that the sound of the group to be as good as you would get from a recording. This is because the recording is made in a deliberate, very refined setting; whereas the live performance either does not do this, or does so in a very different manner.

Robinson: Even some classical concerts are using things like sound reinforcement and PA systems, some of which are of very dubious quality. You go to a "live" event and what you end up with is an amplified event with, in many cases, rather poor sound quality.

Ma: In a sound-reinforced concert hall like the Royal Festival Hall in London, where you can have a "live" performance, but it’s supported by amplification, 175 amplifiers and all that, the problem is that the operator or the engineer may have a "different perception." This is a polite way of saying it! Or to put it rather bluntly, he is not an audiophile! (general laughter) He may love disco, but he doesn’t understand classical music—the Mozart that you played for me earlier today, for example—he would equalize it to make it sound the way he likes it. This is a kind of musical murder.

This reminds me of a joke; one about the rabbit and the snake. Once upon a time, during the night, a rabbit encountered a snake. Because it was so dark, neither the rabbit nor the snake could tell what the other was. So they touched each other. The snake touched the rabbit and said, "Ah! You are so soft and warm, so smooth." And the rabbit said, "Yes, I am." The snake said, "You have long ears, so you must have good hearing. You must be an audiophile!" And the rabbit said, "Yes, of course, I am an audiophile. Let me touch you, sir." "OK," said the snake. So the rabbit touched the snake and said, "Hmmm, you are so cold, rigid, hard and coarse—and you don’t have ears! You must be a recording engineer!" (general laughter)

Gardner: I thought you were going to say "reviewer"! (more laughter)

Ma: There is some truth in it. I think that I can call myself a "record producer," and I have seen occasions where the engineer did not see things eye-to-eye with me. As a result, I got a very bad recording. It’s proven in my catalog; those recordings (where this happened) are ones with which I am not satisfied, but the recording engineer thinks that they’re great.

Gardner: It would no doubt require a great deal of time and thought to go back over the experience of constructing your room, but I have a summary question for you: what one thing that was most important to you did you learn out of the experience of building this room?

Ma: OK, a different person may give a different answer. My answer is that—over the years—I have seen so many well known audiophiles who are in possession of audio systems. They have different preferences and references. I have my own reference. For that matter, there are also many audiophiles who do not have a reference. They may support a speaker that has very good high frequency; they go for it. Then they change to another speaker, because it produces wonderful bass. And they will say that it is "good sound," when actually, it is not good sound, because, as I said, that person may be a disco lover. This audiophile does not have a sufficient reference, or any reference at all, and so he will sell his old system in favor of a new one. It is possible to have no reference, or an insufficient reference, or a wrong reference.

So, in answer to your question, I would say that the process—and the reward—is that I have strived very hard to get the sound as close to my personal reference, (which is how I feel the music) in my heart, and I am working in that direction. I am happy to say that that (the sound in my music room) is quite close, very close to my own reference.

What is my reference? It is very abstract. If you have some of my CDs (or SACDs) you always will find that they sound in a way that people will say, "Ah, this is Winston’s sound!" Whether it is good or not, we’ll not argue that point! For that matter, you have Decca sound, or EMI sound, or Three Blind Mice sound, but I have my own sound. That kind of sound is your own reference. And I am trying to make that sound in my own music, and I would say that I am close to this (in this room).

Gardner: David and I have talked about this issue on a number of occasions, about "the absolute sound," where that resides—whether that resides strictly in the definition of "unamplified acoustic music"—live music as a reference. I’ve heard it put most cogently by someone from Acoustic Sciences Corporation (ASC), the room treatment company, who explained to my wife… in a moment of my absence!… that every audiophile has an "absolute sound," and it’s in their head! And that’s what they’re trying to get in their system; they want to get the external world to sound like the ultimate sound they carry around in their own head. Is that what you’re referring to, that you carry around in your heart and your mind what that reference really is?

Ma: Further than that. That reference must be accurate, and not the wrong reference. Say that you want one foot, then you must have a ruler that is exactly one foot long, instead of having a ruler that is nine inches or eighteen inches. I would say that the reference must be closest to the original sound. When you say that everyone has a "reference sound," I would say that everyone has their preferred sound. As the saying goes, "one man’s ceiling is another man’s floor." And, with due respect, some preferences are terrible!

Gardner: And so live music, the original sonic event that was recorded, remains for you the reference?

Ma: If I give you an honest answer, I would say that it comes as it is. I have my reference; whenever I visit homes or systems, or go to a studio, I always go back to my (internal) sound… that is my reference. Whether that is "live music" or not—because, as we have discussed, sometimes live music is bad, or is lacking in certain areas. My reference is a yardstick in my mind, to measure anything against.

Robinson: I think that anything that makes us approach oneness with the music, that brings the music within and transports us there, that is the sublime experience that we’re looking for. Harvey Rosenberg has called it "the search for musical ecstasy"; he wrote a lot about ecstasy in audio. This is probably the most important contribution that Harvey made to the discussion. He has pointed out in his writing that audio has the capability to help the listener achieve that ecstasy and oneness.

Ma: More than listening to live music.

Gardner: Sometimes!

Ma: Most of the time—because you have control of the sound. If you tune your system in such a way that one night you jump out, and tell your wife, "you’ve got to listen to it, it’s so good!" then yes, that’s a kind of ecstasy.

Paul Weitzel, Rick Gardner and Winston Ma converse about music

and listening room design

Robinson: In a public setting, you can’t actually jump up and dance, or say "Stop! I’ve got to get my friend to come here this!" Or, "Let’s hear that again!" Conventions, traditions, and politeness require that we simply sit back and accept whatever comes our way. We can’t say, "Wait, if we do this the sound will be better," or "Let’s move the band here," or "This room needs to be re-worked." I think that with the tools we have in the audio arts—with the listening room in many ways being the most critical—we can actually create a place in which great magic happens.

Ma: True, true. If I were to choose the proper order of priority, I would put human perception first, the room in second place, and the equipment last. Without a good room the equipment, no matter how good it is, may sound terrible.

Robinson: This is where the listener IN the listening room is of critical importance. It’s more than just a question of having a person there; the listener must be a person of sensibility. Scott Frankland has written in PF about the audio connoisseur, a person who has given of himself, and has trained his sense to know what is good and what is not good. He has put in his time, as you have put in many years listening and working with music and sound, so that you would recognize the real thing if it was there.

Winston Ma with his listening room design book

Ma: Yes, yes.

Robinson: It’s not enough for me to say, "well, if we put the right room together, that’s it," because a person who has no sensibilities might simply walk right past it. Or look once, say "oh, very pretty," and keep going.

Ma: And in fact, many a time when you ask a person how the system sounds, how it differs when you make a small change, he would simply say, "I don’t know." This is because his level of sensibility and his level of exposure and experience is not able to discern the difference.

Gardner: One of the things that has struck me most profoundly in the two experiences that I’ve had here at your music room goes beyond the pure sonics of it. The design of the garden, the positioning of the listening room, the ritual of the tea, the quality of the conversation with you, the aesthetics of the room separate from its acoustic properties, all are part of that experience. They aren’t things that you can separate from it. I have been in a lot of listening rooms where I was physically not comfortable, I didn’t feel at ease, I didn’t feel peaceful, and the whole experience of coming here, it seems like it’s all designed to work together as a coherent whole. I think that’s a unique kind of achievement, and not one that I’ve ever really seen before.

Ma: I would only add that it is my endeavor in the pursuit of the so-called "perfect music room," because, as you have pointed out, there may be some rooms which are very good sounding, or perhaps better sounding than this one… (general laughter)

Robinson: If so, then I haven’t heard them!

Gardner: I haven’t either…

Ma: There are many times when you go into a listening room and it is good, but you aren’t comfortable. It’s either too sloppy, or too cluttered, or too mechanical. So you don’t feel that you are close to the music. We tried to make this music room not like a "music room."

Robinson: I find the sound in your room to be superior; there’s more of a sense of presence, of life in your room, a sense of feeling the music blossom and float…

Ma: … enveloping; you feel the dynamics and energy of the music. Certainly my room is not perfect, there are other ways of improving certain aspects, but it is a give-and-take situation. You may improve one thing, but lose something else.

Gardner: The description I would give you is that of large Cineplex type movie theatres. These are modern, state-of-the-art facilities that are carefully designed, have the best equipment, and are put together very, very carefully. But the experience of seeing a movie in a theatre like that, as opposed to one of the old-line—I’m thinking of the Egyptian theatre in Boise, Idaho, which was built in the early 1900’s, and has the full Egyptian columns and all of this character, including its own very unique way of sounding and looking—that experience is fundamentally more nurturing than something that might be technically more correct. And that’s the kind of experience I have in your room; without growing too philosophical, it is at the same time very reflective of your personality, a strong philosophical element that runs through the whole way that it is set up. The experience is fundamentally different and more nourishing than something that might be more "technically correct."

Ma: Well, nobody can tell. It’s more human, I would accept that category; whether it is "correct" or not may take some twenty years to see whether this room is "technically correct." This is because mankind knows so little about acoustics. But as it is, all the "tricks" I do, I would say have some technical or scientific rationale, a basis to work on, and aren’t based on pure imagination.

Robinson: This is what makes a true "classic." Despite the changes in technology, a Stradivarius is still a Stradivarius.

Ma: Exactly! And you can technically analyze the difference between another violin and a Strad; the Strad has its own magic. A Steinway has its own magic; how can you find out exactly what it is?

Robinson: I think that the things that are true and classic acoustically will always be true and classic. What will happen when, for example, we put SACD in your room, will be that new possibilities and new truths will be revealed within your music room.

Ma: Yes, yes.

Robinson: And I believe that there are things that are fundamentally true and right, and other things that are fundamentally untrue or wrong, and advances simply expose if you have done truly, wisely, and properly. If so, then that’s why we call them "classic." That’s why we still read the great classics of thousands of years ago; they were right and true and proper, and they have stood the test of time. I do believe that there are great listening rooms, and great audio components, that decades later we still know that they are great.

Ma: Yes, yes.

Part three of PF Online’s interview with Winston Ma will appear in Issue 3.