|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE

15

The Audio Century, Part

II: The Twentieth Century and the Birth of Audio Technology - Some thoughts on

where we've been, and where we might be going.

(footnotes by Robinson) Way back in Positive Feedback, Vol. 8, No. 4, John Pearsall published some reflections on the history of audio. As part of PFO's program to re-print vintage PF articles, we are re-publishing John's fine overview of our audio past. "Those who don't know the audio past are doomed to bad mojo," said Gorgeous George Santayana, Jr.—and "The only thing new in the world is the history you don't know," said Harry Truman. Yep. To learn more, read on, pilgrim… And by the way, if you missed Part I of John's extraordinary history, you'll find it in Issue 14 at https://positive-feedback.com/Issue14/pearsalla.htm. Enjoy! The Vinyl LP: Chapter Two (This time in stereo) Ask any audiophile who's been around for a few years, "What's the watershed year for the modern sound era?" The usual answer will be "1958." The Fall of 1958 was the earliest that a pioneering soul like myself could expect to find more than three stereo LPs and a stereo phono cartridge to play them with. Early stereo LP playback was crude. 1958 stereo phono cartridges were pretty disgusting (mostly quicky adaptations of old mono designs), and almost none of the turntable engineers had even thought of the mechanical needs peculiar to a Westrex 45/45 LP.

Incidentally, since stereo demanded two speakers in our music systems, it was fortunate for the small listening space that AR's (Acoustic Research) co-founder, the aforementioned Mr. Villchur, had developed and patented his groundbreaking acoustic suspension speaker in 1954, the AR-1. It gave us small size and the damnedest bass you ever heard from any speaker, much less a compact one. The highs were dull, but that bass response could put a smile on your face and upset your landlady. Not yet ready for prime time, stereo music for the wider market had arrived on LP. Stereo tape, in the stores since 1955, was still the best sounding medium we had. The stereo LP became available in greater numbers, and listening quality improved as the record companies learned how to make them, and the turntable engineers burned the midnight oil. By 1959, the recording schedules at most major labels became crowded with the 20th century's biggest artists re-recording most of their mono repertory in stereo. In 1959, the Golden Era was here, though I'm not sure we knew what we had. The stereo LP began hitting its stride and the technology was mature enough that the studio engineers quit straining for ping pong, left-channel / right-channel nonsense and focused on depth, detail and localization. In the stereo turntable arena, the hardware race was at full gallop. Turntable, tonearm and cartridge manufacturers were finally engaged with their new mission because the stereo LP was a very demanding medium and the discerning consumer wanted better LP playback equipment. Phono cartridges took a giant step forward when Danish Ortophon and American Shure put enormous effort into a detailed analysis of stylus behavior in the record groove. The highway metaphor for groove tracking would be, "where the rubber meets the road." In the next several years, the payoff from their cartridge research was astounding. Others contributed, too, but Shure and Ortophon formalized tracking performance criteria and quantified the most crucial factors of groove tracing. Both companies studied the effects of stylus shape, cantilever mass, cantilever compliance and the effects of vertical tracking angle. Much of their work found its way into their premium phono cartridges in 1964/65. Thirty five years ago this year, most of the groove tracing parameters became known, and the record listener could finally appreciate how good the stereo LP had become. I'm an old fan of vinyl and I still enjoy my LPs, but for being a relatively crude electro-mechanical medium for the storage of music, I still marvel at the LP's musicality. LPs have many faults and their playback has been likened to "dragging a polished boulder "dragging a polished boulder through a vinyl canyon", but, damn! don't they sound good? Like the curious case of the Bumble Bee, an aerodynamic disaster from an engineering viewpoint, the LP operates in its own realm of improbability, yet somehow they both fly! The LP and the Bumble Bee are soul-mates. Who'd-a thunk it? A Little Corrosion on the Golden Age: 1960 - 1963 On today's Oprah - "Your ring turned my finger green!" Corporate Disaster #1: Half-track, real-time stereo tapes disappeared from the retail shelves. Closed-out. Eighty-sixed! Forever. Or as Agatha Christie's Miss Jane Marple would describe it, "Murder Most Foul!" The quarter track playback standard was forced on their loyal open reel tape customers without so much as a "By your leave." Industry poo-bahs assured us in honeyed tones that 4-track tapes were somehow superior! (Maybe because you didn't have to rewind the suckers. You could just turn them over and you were back at the beginning. See?) Damn! How did I miss that? Oh, they were cheaper, too. To buy and to make. Clearly, the manufacturer's accounting department made this decision for us. Automated high speed, quarter-track duplicators (4x to 8x play speed) came on line, and the fallout was serious crosstalk, clobbered highs and echo problems. Dynamic range went to hell, too. This unfortunate corporate decision compromised everything we loved about our half-track tapes. Then they threw another one at us. The long playing tape standard became 4-track at 3 3/4 IPS! Instead of using multiple reels as they had done, they doubled the playing time per reel, and put a whole opera on one tape? Progress? No. The tape was a pale version of the previous release. (It's not unlike finding a scarce movie on VHS, only to discover it was duped at EP in some backroom operation in the bayou country.) Once again, we took it in the shorts with open reel's industry forced regressive technology decision.1 The seeds of open reel tape's eventual death were planted way back in 1960, and with typical corporate eagerness to lower technical standards in the name of profits, the fate of high-quality tape was sealed. Open reel was gravely ill by 1970, and was totally dead in 1976. (I'm surprised it lasted 16 years after half-track's demise.) Ampex tried an 11th hour revival in 1975 with the introduction of 7 1/2 IPS Dolby B noise reduction with greatly improved processing Q.C., but it was too late. Though the product required an outboard Dolby B adapter, the tapes sounded damned good. But by then, nobody cared. In remembering Freddie Mercury's great song, we observe, "Another one bites the dust!" 1 The history of audio is strewn with regressions in quality in the name of the "bottom line." All the more reason to rejoice over the arrival of DSD/SACD, the first true progression in audio standards since the days of half-track open reel. May it "live long and prosper!" Corporate Disaster #2: In the world of classical music recording, RCA producer John Pfeifer and his star recording engineer, Lewis Layton, were the absolute gods of the recording universe. The Golden Age of the LP was defined by them. The vinyl collecting audiophile still burns incense at the altar dedicated to them. They could do no wrong. Then, out of nowhere—SPLUTTT!! The fecal matter hit the rotating blades! The era of Dynagroove, RCA's corporate wet dream and boardroom brain-fart nearly eliminated RCA Red Seal LPs from any serious collector's buying list.

But when RCA signed their pact with the Devil, the remarkably lifelike vitality of their award-winning sound went out the window before the ink was dry. "Progress," again? I don't think I can take it. RCA's mastering process quickly became known as "Dynasludge." I tried their much ballyhooed initial release in early ‘63. It was the Leinsdorf/Boston Symphony recording of Mahler's 1st Symphony in a flashy, special edition concept cover. Nice packaging—but not a happy listening experience. Bloated, soggy, opaque. I stopped buying new RCA releases bearing the Dynagroove logo and bought only the pre-Dynagroove LPs for a long while. Eventually this ill-fated process was quietly swept under the rug by the mastering lab at RCA. Many of their records were still marked Dynagroove, but they sounded much like the older product, sometimes better. Their core audiophile customer base evaporated, though. They simply quit buying RCA LP's; by now it was too late to get their credibility back. By 1963 my record collecting friends wouldn't touch RCA Red Seal with a barge pole. Through the rest of the LP era, even when RCA proudly rose to its former brilliance, and they often did, many record collectors didn't trust the product. As a result, many vinyl folks missed out on some stellar releases produced after the Dynagrunt fiasco. It didn't stop me, though. I cheerfully bought many of RCA's cut-out LPs in the late 60's for a buck a record. It's all in the knowin' — oh, yesssss! "There's a kind of hush, all over the world tonight" His name is Ray Dolby and he's still around. An experienced former Ampex engineer, Ray Dolby developed the first widely used noise reduction system for commercial recording. In 1967, Dolby Labs introduced a sophisticated multi-band noise reduction system called Dolby A. Designed to prevent most of the cumulative noise buildup from the original session taping and the studio processing steps afterward, it was first utilized in 1967 by British and American classical recording teams. I still have the first American release, Stravinsky's A Soldier's Tale, a small Faustian musical drama with spoken parts and narration. The sessions were recorded on the Vanguard label at their New York studios with superb, hand-picked chamber musicians and a top French acting ensemble. The two LP set, recorded once in French and again in English, still sounds incredibly good. Thirty-three years later the Vanguard LPs are still probably the best Soldiers Tale ever recorded, and a memorable first project for Dolby A noise reduction. Maestro Stokowski had the Stravinsky magic in his bones and he was almost 85 when this was taped. A Little Something for the Public Airwaves: Eine Kleine Stereo Nachtmusik FM broadcasting was the last non-stereo frontier. By 1962, the North American multiplexing standard for FM stereo became official. The once-great American electronics giant, Zenith, was the winner of the engineering competition. Sadly, the early stereo tuners with their hastily cobbled outboard stereo adapters, were a total pain in the tush and disappointing. They lacked stability and adequate separation and drifted like crazy, but in less than three years, FM Stereo had gotten pretty good. First, 2nd and 3rd generation multiplex circuitry became inherently more stable and was designed as an integral part of the overall tuner circuitry instead of being an "add on" option. Secondly, the use of well-executed transistor tuner circuits added needed stability, compactness, simplicity, got rid of tube drift, and lowered the overall cost. Tuners, incidentally, were the earliest audio circuits where transistors worked exceptionally well. That was not the case in most other early transistor audio circuitry. FM stereo was a solid product by 1965, and I enjoyed at least 4 good stereo stations here in Portland and a stable H.H. Scott tuner used to receive them. The Transistor Revolution: Ten Years of Wandering in the Desert! Transistor audio amplifiers in their first five years (how do I put this charitably?) weren't very good. Actually, they sucked! In fact, they sucked swamp water!! The first generation transistor sound tended to be insufferably dull and harsh, simultaneously (McIntosh); constipated and flat, (Marantz); and gritty and dreadful, (just about everyone else). With huge amounts of gain available, the early transistor circuit designers applied massive negative feedback correction to amplifiers, resulting in sound that was cold and irritating and couldn't handle transients worth a damn. Early transistor circuits produced superb static sine wave distortion numbers and some fairly decent looking square waves, but that's the easy stuff. Real music isn't sine waves. Real music isn't symmetrical. Real music doesn't obey the static testing rules. Compared to highly accomplished tube amplifiers of 1967-1968, capable of sounding limpid, smooth, warm, dimensional, slightly sexy and real, the 1968 transistor amplifier standard was arid, closed down, two-dimensional, irritating and cold. The new amplifiers had no juice. They were not seductive and warm. They were not euphonic. After months of listening to various new designs from the major vendors, it was evident that this was not the arrival of "perfect sound" or even improved soundnot the arrival of perfect sound or even improved sound. Solid-state Nirvana was not gonna' happen. Pre-amps from top makers were closed in, murky or just plain dull, and power amps could sometimes blow their expensive output stages in a heart beat. (An exception was Mac with its autoformer isolated outputs. You couldn't kill these massive suckers with a fire ax, but you wished you could so you could collect a vandalism claim.) Fortunately, starting out verrrry slowly in 1971, the best circuit designers quit thinking tubes and began to master the current amplifier nature of transistors. Good silicone power devices in complimentary pairs became available, thanks to Motorola, RCA and a few others. Semi-conductor science improved markedly, too. Low noise, wide bandwidth complimentary pairs of low level silicone devices specifically for audio use were developed, so line stages and pre-amps improved. Power devices became rugged and sophisticated. The engineers gained experience and developed novel ideas on how to use the new devices, not like tubes, but like transistors. Engineers were finally doing some original designing with solid-state technology. It was long overdue!

I dumped out of my

McIntosh transistor gear (2105 and C-26). I replaced it with the English Quad 33

and 303 transistor pair. Very British, quite musical and endearingly quirky. I

became happier with my sound than I'd been in three years. Coming out of my

speakers was sound that fell gently on the ear, sweet, no buzz saws, and I was

able to relax. I mourned a lot less about the fateful day I'd foolishly

abandoned my Mac tube gear in the name of God knows what! (MC-75 mono blocks and

MX-110 tuner /

The second half of the seventies brought big progress to transistor audio design. Mati Otala in Scandinavia was joined by several other European and American designers who pointed out the pitfalls of using massive negative feedback. They demonstrated that judicious use of negative feedback, properly applied, is the way to go. Almost in unison, they advised going for small amounts of feedback and came out foursquare against being a slave to test numbers. The very best engineers began forming expert listening panels to evaluate their products "by ear" again. Amps began to sound more musical by 1977 and 1978, more vital, a lot less harsh and congested. I ended up buying American-made Harmon/Kardon Citation gear (Citation Models 17-18 & 19), and I kept it for several years. Good stuff! The 1970's and beyond Whither open reel tape?? Whither indeed! Dead as the proverbial doornail! (What the hell is a doornail, anyway? Everybody refers to a doornail being dead.) Recorded tapes were effectively off the retail map by 1976. Open reel machines, though better than they'd ever been, went into a gradual dignified decline that virtually ended their existence by 1990. The beautiful open reel machines remind one of the Tennessee Williams more interesting characters, Amanda Wingfield, fondly remembering the gentleman callers of her youth. Then she realizes there are no more cotillions on her calendar. And no more gentlemen callers, either. The less talented audio cassette, though handy for the car, continued to languish in restless mediocrity through the ‘70s until sometime in the mid-‘80s, when it became a surprisingly musical-sounding mass medium. The best of all the analog tape cartridge systems was the El-Cassette. Sold for only two lackluster marketing years in the mid-70's, the format died. Why? Too many formats and, by now, a highly skeptical public recently burned in the format wars, the surround debacle, and other games of musical chairs. Speaking of musical chairs... Genesis in Four Channels: CBS Labs begot SQ - SQ begot Sansuii QS - and RCA whispered discretely, "We reserve the right to be tragically wrong with CD-4" The multi-channel surround sound war of the early 70's came to a confusing, lurching halt. All the combatants died on the battlefield. There were no survivors. And the public, as usual, picked up the burial costs. CBS/Sony launched the SQ Matrix 4-channel system in late 1969 with much fanfare, only to witness Sansui Electric of Japan introducing a competing and similar matrix scheme called QS. Get it? QS? SQ? (You say tomato and I say tomahto. Let's call the whole thing off!) Last, but not least, and refusing be denied their God-given right to be wrong again, RCA, this time in partnership with JVC, introduced their ambitious frequency-modulation sub-carrier variant for LPs called CD-4.

Fortunately, there was this time: in the ill-fated CD-4 adventure, there were two very positive benefits for the LP playing audiophile. First, phono cartridge engineers really got busy. Cartridge engineering reached its highest levels ever in 1975 to meet the demands of the fussy sub-carriers. Second: new vinyl pressing compounds were developed to conquer the CD-4's ultra-sonic wear problem. The new vinyls proved to be superior in the Direct-to-Disc LP pressings of the late 70's and early 80's. In addition, intensive research went into new stylus shapes and led the way for lower distortion stylus tip profiles for super high-frequency tracing on LPs since 1975 . Once more, bring out the black arm bands All three surround systems died by 1976. The customer was left with an odd assortment of extra speakers, quadriphonic boxes, bitter memories and no music to play on it. (RCA wasn't finished embarrassing themselves yet. In the early ‘80s, RCA hatched a mechanically traced video disc system called Selectavision, once again with Japanese partner JVC, and tried to unseat the optically read Philips/Pioneer Laservision system. Selectavision tanked in less than two years. Another bruising write-off for RCA. Toward the end, Radio Shack was giving away the players and discs for nickles on the dollar. Today they are dumpster stuffers.) The beginnings of "High-End Audio," Or "Toys for boys who read Playboys"

As we donned our polyester leisure suits and had our hair permed in the "go-go" 70's, impressive upscale components evolved from standard pro-gear conventions such as rack-panel mounting, rack handles, BIG knobs, daring new visual designs incorporating a funky industrial look, high quality metal work, massive construction, reasonably well executed circuitry—stuff loaded with tons of macho mystique. The emerging high-end audio gear in the late seventies reminds me of the endless lines of gas-chuggin' SUV's on our highways these days. Everybody has to have one and they don't know why. Leaving the ‘70s behind, the new upscale audio toys were lavishly and alluringly presented to salivating status seekers of the Reagan ‘80s. The leisure suits were gone and the hair shorter. BMW and Mercedes joined the parade, and luxury components began to dominate the sound rooms of stores that now billed themselves as salons. Incredible looking amps and speakers and turntables fairly oozed major mojo! But, the equipment, as nice as it was, began an unfortunate, escalating price structure that has harmed serious audio in some very major ways. Snob appeal vs. value for money. Value for money frequently lost out. A vexing question gained prominence in marketing conferences of the late ‘80s. This factor was not covered in my Econ 101 classes. The merchandising concern was, "Have we priced our product high enough to have major credibility?" Audio marketing policies seemed more related to "Reaganomics and Gold Mastercards" than to the audio hobbyist with four kids and a mortgage. This is a kind of audiophile "priesthood" that actually has very little to do with music or the arts. About which more in Part Two. The Compact Disc: Digital Perfection into Eternity and Beyond - (in theory, of course) An all digital format that had been rumored for several years finally arrived. "Digital perfection for ever and ever. Amen." proclaimed the ad copy circulating in late 1982. Sometime, if you want an afternoon's entertainment, dig out some back issues of the last three months of 1982 from various popular audio mags. It doesn't matter which ones you choose to read. Look at the laudatory comments ladled on early CD player prototypes and production units sent to major reviewers during that annual mating dance that has only one purpose: the ritual whetting of consumer appetite. It's also known as the critical "product launch window." I suspect that several of those reviewers would like to take back the fawning commentaries published under their by-lines in Fall/Winter 1982. Once again, the silly old Emperor, with teeth chattering and goose-bumps all over his scrawny pink body, was found "butt-nekked, starkers, and widdout' no clothes on." Several the most notable scriveners of the audio publishing priesthood somehow failed to notice the awful, parched sound coming off those little silver devils. Where in blue, bloody hell had they parked their sensibilities and their "golden ears"? Of course, time catches up with all of us. Eighteen years have passed since then and some of the scribes now sit atop that great Klipschorn in the sky pondering the eternal question, "Is it live, or is it Memorex?" By the mid-‘80s, though, those reviews raised serious doubts about reviewer listening judgment. Alas, sometimes audio reviews seem to derive from which side of the toast has the jam on it. Or maybe their analog souls fell under the unholy spell of 1's and 0's and they just got it wrong.

At that point we put the player back in the carton and called it a day. And I tried to find the cat. Was this another disaster scenario with which the audio industry routinely wounds itself every few seasons? The earliest CD players were a sorry lot. Some of them were top loading, some vertical loading; there was almost no drawer loading available; they were cursed with nasty sounding brick-wall analog filters and skimpy 14-bit resolution. They had no over sampling methods in place, had sloppy clocking circuits and multiple, hot-running, stacked circuit boards, chock full of generic IC's. Like I said, a sorry ass lot. Without exception, the first shipments of players produced a sound that was decimated, desiccated and constipated. I got to thinking that year, "This can only get better." Fortunately, several years down the road, it finally did. "Presenting the Ginsu D/A converter: It slices, it dices, it quantizes" My major disappointment with CDs in the Spring of ‘83 was partially traceable to that first batch of CBS titles released in the U.S. to support Sony's first player. Therein lay half the problem. Rumor has it (and I can't prove it) that the CBS vault people in New York sent analog cutting masters to Tokyo's CBS/Sony plant for CD mastering. I was told the equalization had a nasty rising top end and other assorted non-linearities. Unfortunately, the resulting CDs were execrable. About a month later, Telarc produced their first CDs. They weren't fierce at all, but just the reverse, unacceptably dull, lackluster, wooly. They bore little resemblance to Telarc's rather impressive sounding LPs from those same Soundstream digital masters. Philips CDs arrived in the summer and theirs were an inconsistent mixed bag, a bit schizoid. Denon of Japan delivered CDs in 1983 that were fairly decent, but only if they were from Denon's most recent digital masters. Alas, Germany's classical giant, DGG, got it all wrong. Their CDs sounded nasty, wiry and dry. Finally, and much to my relief, the first musical CDs began reaching me in the fall, this time from London/Decca. By late 1983, there was a ray of hope that CDs might succeed after all. The second generation players and improved CDs helped confirm that notion, and it seemed unlikely that the two biggest companies in consumer electronics would be that careless with their sizeable investment. My reaction to this early period of the CD became watchful caution. I didn't stop buying LP's. Others were selling their LPs and buying little silver devils at 17 bucks a whack! Good used market! In ‘84, ‘85, and ‘86, everybody and his brother-in-law began marketing a CD player under their house name. Most of this odd lot, claiming unusual features and magical qualities, were sourced from a small number of vendors around the world. They were mediocre at best, and disappeared quickly. I auditioned a few dozen players every year during the mid-80's. Manufacturers reps brought them over seeking my opinion on whether a given design had a snowball's chance. Most of them didn't. It was, indeed, a motley parade. I didn't buy a player for myself until late 1987 and, even then, I had some misgivings. By 1987, however, CD playback circuitry and transports had reached 4th or 5th generations technically, and various over-sampling methods, sophisticated filtering and clocking schemes had been devised. The new D/A converters were much improved. Analog filters, still very necessary to eliminate the harsh digital artifacts were eventually revised, refined and simplified. At last, I could live with the results. It had taken more than 5 years for the compact disc to become musical enough to win a place in my system. Even longer to win my confidence. The Digital Revolution: A major fallout for all who now live on Planet Earth The digital revolution is a real and bona fide revolution! Believe it! There will be very little in our lives that won't be changed in some way by digital technologies. The implications for our culture are profound and if we look at audio technology, we're already 25 years into audio's earlier mini-revolution that started with Japanese Denon's first halting attempts at digitally recording music in 1972, using early circuitry with early IC's and transistors. Achieving 12-bit resolution and marginal listening quality, it wasn't fast enough and lacked the resolving power to be convincing. Fully digital recording and CD playback for the home had to wait until 1982 when circuits and semi-conductors had caught up with the engineering requirements. The first acceptable digital recordings I heard on LPs were done in 1977. The 3M recording system and Tom Stockham's Soundstream system sounded pretty good. Not many people seem aware of the origins of today's audio technologies, but digital audio is a spin-off of communications research done for the American and Japanese telephone monopolies. Early digital research sought to achieve economical and stable voice and data transmission in global communications systems. Of course, digital encoding is a major turning point in any discussion of 20th century audio or video recording, playback or transmission. Nothing will ever be the same again in consumer electronics and already, the digital processes have taken over most land-based and satellite data transmission, as well as all the new audio and video formats, the digital desktop computer with its increasing role in our daily activities and in medicine, too. Even the color plotting of blood flow in my aging arterial system was digital. Tracking injected radioactive-isotopes in my bloodstream, a specialized digital computer generated beautiful color images of my blood flow before and after my "trial by treadmill." Puff! Puff! (Incidentally, my arteries looked impressively dazzling in living color. And open.) Back to the digital revolution: As Al Jolson said about the "talkies" in 1927, "You ain't heard nothing yet!" With the new technologies, I would add, "You ain't seen nothin' yet!" Almost every field of human endeavor will be changed by digital methods, most heavily in the next two decades. Pay careful attention to the anticipated changes of the next few years: We've only just begun! (Remembering the late Karen Carpenter, the purest alto voice in the annals of popular music.) I've tried to keep my remarks in the "audio century" germane to the serious discussion of audio technology and the question of audio's survival as a hobby pursuit. Approached as an art from and used as a positive force for enjoying our world's vast musical treasures, some form of our audio hobby must survive! My intent for Part Two of this article is to lay a foundation for discussing audio and its internal workings, past and present, so that we may insure that it survives. I hold some strong views on how the pursuit of audio has changed through the years. Some of the changes have proven beneficial; others have not. But, change is the one absolute certainty in life that's as regular as daffodils in March. It always has been. So, let's look at some of the important questions we should be asking about ourselves and our hobby: Where is serious audio headed in the immediate future? Where will serious audio be at the end of this decade? Will audio activity retain the primary goal of listening to music, or will it merge with the much larger multi-media future of the new century? Will audio become merely an appendage to the video revolution? Let us at Positive Feedback Online know what you think about all this; we'd like to hear from you. In a future installment of the "Audio Century", there's another subject that has to be discussed: mentoring. Mentoring is especially difficult when there is so much competition for the smaller amounts of spare time we can devote to an activity. If serious audio is to survive, however, who is going to replace us when we join those already sitting atop the great Klipschorn in the sky? What will we tell a newcomer if he or she expresses an interest in high quality sound? How can we help audio hobby activities adapt to the realities of the 21st century marketplace? How can we avoid the friction and loss of civility we've experienced in the last 20 years? How can we avoid excess philosophical infighting and the adverse impact from cult-like behavior that appears in audio from time to time? Can serious audio be weaned from the psuedo-scientific nonsense that occasionally surrounds it and be steered back toward being a true art form that informs itself with solid science? In future, can we manage to enjoy audio technology as a means to an end, the end being the deeper appreciation of music? Or will the means be their own end and forever dominate the equation to the detriment of art? Is the pursuit of sonic spendor going to remain a frightfully expensive exercise in technology chasing after rainbows? Stay tuned for these and other pregnant questions that I hope to address in a future article in Positive Feedback Online. Dedication: I would like to dedicate this article on the "Audio Century" to my friend and long time colleague, David G. Morris. Last March 23rd, 1999, David had a fatal coronary and left behind his many friends in the audio and train club communities. David was my friend for over 31 years, and his early death at age 54 has left a large void in my life. A dedicated audio enthusiast, David's 2000 sq. ft. house featured three audio systems plus a video surround system. Having logged three decades in his audio hobby, he was also a regular at the Oregon Triode Society meetings in the early 90's. His insightful observations and the discussions we had through the years have influenced this pair of articles in very positive ways. I still reach for the phone to tell him the latest news because he was there for so many years. Now he isn't…

|

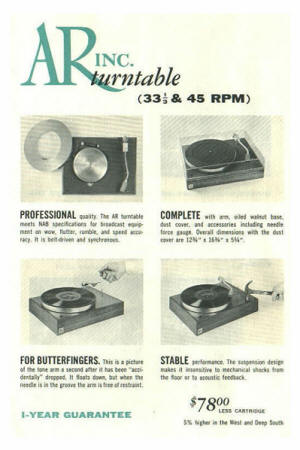

Turntable designers had

largely ignored the vertical rumble axis in the days of mono LP playback. It was

virtually a non-issue. The stereo LP, however, forced the rethinking of all

platter and bearing mechanics in turning LP records. Old fashioned, commercial,

brute force DJ turntables were the best we had in early stereo LP days. They had

big motors, precision idler wheels and heavy platters on reasonably good

bearings. They could spin a small child until he upchucked and achieve full

rotation speed in a half-revolution. In their off time, the studio turntables

made dandy potting wheels. But, they had to carry the freight until the newer

belt driven designs got good enough. Adequate environmental isolation for a

turntable was still a couple years away. From a loudspeaker engineer, the 1961

introduction of an odd, wiggling, floating, un-glamorous, utterly simple

miracle, the ubiquitous and much imitated AR turntable from AR's founder

and chief engineer Edgar Villchur. The AR turntable showed everyone else

how to isolate a unified platter/arm support assembly from the outside world. It

was floated on ultra low resonance springs and ignored anything up to a 5.6 on

the Richter Scale. Most belt drive tables today, 40 years later, still use the

basics of Villchur's design. (There were once a couple of American designs that

floated the platter mass on opposing magnetic fields. Of course, the arm

wasn't floated with the platter. Ooops!)

Turntable designers had

largely ignored the vertical rumble axis in the days of mono LP playback. It was

virtually a non-issue. The stereo LP, however, forced the rethinking of all

platter and bearing mechanics in turning LP records. Old fashioned, commercial,

brute force DJ turntables were the best we had in early stereo LP days. They had

big motors, precision idler wheels and heavy platters on reasonably good

bearings. They could spin a small child until he upchucked and achieve full

rotation speed in a half-revolution. In their off time, the studio turntables

made dandy potting wheels. But, they had to carry the freight until the newer

belt driven designs got good enough. Adequate environmental isolation for a

turntable was still a couple years away. From a loudspeaker engineer, the 1961

introduction of an odd, wiggling, floating, un-glamorous, utterly simple

miracle, the ubiquitous and much imitated AR turntable from AR's founder

and chief engineer Edgar Villchur. The AR turntable showed everyone else

how to isolate a unified platter/arm support assembly from the outside world. It

was floated on ultra low resonance springs and ignored anything up to a 5.6 on

the Richter Scale. Most belt drive tables today, 40 years later, still use the

basics of Villchur's design. (There were once a couple of American designs that

floated the platter mass on opposing magnetic fields. Of course, the arm

wasn't floated with the platter. Ooops!) RCA, in their collective

wisdom (hubris?), thought it possible to extend audiophile performance to the

record chewing consoles in suburban living rooms everywhere. Improved

performance for everyone! In truth, they had encountered millions of record

players out there in Radio & TV land that couldn't track a pristine RCA

"Red Seal" LP in its1960 glory. Dynagroove was born to insure egalitarian

record playing on any machine, anywhere, anytime. Never mind what it took

away from the audiophile! By means of an analog computer system in the

mastering chain, the computer anticipated cutting demands of an upcoming

passage. Voila! By smoothing out cutting extremes and modifying the

frequency balances on peak passages, the typical home player mis-tracked only

once in a while.

RCA, in their collective

wisdom (hubris?), thought it possible to extend audiophile performance to the

record chewing consoles in suburban living rooms everywhere. Improved

performance for everyone! In truth, they had encountered millions of record

players out there in Radio & TV land that couldn't track a pristine RCA

"Red Seal" LP in its1960 glory. Dynagroove was born to insure egalitarian

record playing on any machine, anywhere, anytime. Never mind what it took

away from the audiophile! By means of an analog computer system in the

mastering chain, the computer anticipated cutting demands of an upcoming

passage. Voila! By smoothing out cutting extremes and modifying the

frequency balances on peak passages, the typical home player mis-tracked only

once in a while.  preamp, 1966 vintage—sniff!) From my painful experience, I

learned that progress ain't progress ‘til the fat lady sings. I continued

leaving burnt offerings at the shrine of my departed Mac tube stuff, and the fat

lady began attending rehearsals.

preamp, 1966 vintage—sniff!) From my painful experience, I

learned that progress ain't progress ‘til the fat lady sings. I continued

leaving burnt offerings at the shrine of my departed Mac tube stuff, and the fat

lady began attending rehearsals. The CD-4 system, designed

to give the user four discrete channels, put extraordinary demands on every

aspect of the record playing chain, the phono cartridge, pickup arm wiring and

turntable signal cables and it depended on a critical FM demodulator box for the

rear channels. Not a matrix system, but an FM sub-carrier discrete 4-channel

alternative, it wasn't very good. In practice, an LP could play only a few times

before the sub-carrier's modulations wore off the groove walls. The rear

channels then became marginal for lack of a reliable sub-carrier. With only

marginal ability to meet FM sub-carrier bandpass demands and inherent stability

problems, the CD-4 system was a failure and another major write-off for RCA in

1976. But I've said it before, "There must be a Pony!"

The CD-4 system, designed

to give the user four discrete channels, put extraordinary demands on every

aspect of the record playing chain, the phono cartridge, pickup arm wiring and

turntable signal cables and it depended on a critical FM demodulator box for the

rear channels. Not a matrix system, but an FM sub-carrier discrete 4-channel

alternative, it wasn't very good. In practice, an LP could play only a few times

before the sub-carrier's modulations wore off the groove walls. The rear

channels then became marginal for lack of a reliable sub-carrier. With only

marginal ability to meet FM sub-carrier bandpass demands and inherent stability

problems, the CD-4 system was a failure and another major write-off for RCA in

1976. But I've said it before, "There must be a Pony!" A smoking jacket and a

lovely pipe. A luxury audio market began to develop in the mid-‘60s. At first it

consisted of a mix and match selection from the early premier companies,

McIntosh, Marantz, JBL, Bozak, Altec, Ampex, Wharfdale, Tannoy, Tandberg, Revox

and a few selected items from the more exotic studio catalogs. By the early

seventies, the market began to change slowly when a several small manufacturers

began featuring "name designers" and going for mystique. Some of them

started as three man garage operations. Others were spin-offs of older firms.

A smoking jacket and a

lovely pipe. A luxury audio market began to develop in the mid-‘60s. At first it

consisted of a mix and match selection from the early premier companies,

McIntosh, Marantz, JBL, Bozak, Altec, Ampex, Wharfdale, Tannoy, Tandberg, Revox

and a few selected items from the more exotic studio catalogs. By the early

seventies, the market began to change slowly when a several small manufacturers

began featuring "name designers" and going for mystique. Some of them

started as three man garage operations. Others were spin-offs of older firms.

I've written about my CD

initiation before, but I'll have another go. I borrowed the original Sony

CDP-101 in the Spring of 1983 and I was given a 5 disc CBS assortment to play on

it. We were listening to very large, very clean JBL horn systems, some of their

latest and greatest. On a pain scale that listening session was somewhere

between adult circumcision and the sudden onset of an ice cream headache. In

stunned disbelief, I asked, "What the bleep! is this kaka?!" The first

discs from the Tokyo CBS/Sony pressing plant were dreadful. Barbra Streisand,

bless her heart, was rendered hopelessly unlistenable with industrial-strength,

buzzing adenoids. The New York Philharmonic peeled wallpaper and neutered the

cat. Miles Davis' Quartet jazz instrumentals were rendered so stridently as to

cause widespread crop failures. And that was just the first three discs!

As far as I could tell, the over-hyped CD medium, though praised with celestial

adjectives by the media types, was seriously flawed and DOA. I not only

couldn't recommend it, I couldn't even listen to it.

I've written about my CD

initiation before, but I'll have another go. I borrowed the original Sony

CDP-101 in the Spring of 1983 and I was given a 5 disc CBS assortment to play on

it. We were listening to very large, very clean JBL horn systems, some of their

latest and greatest. On a pain scale that listening session was somewhere

between adult circumcision and the sudden onset of an ice cream headache. In

stunned disbelief, I asked, "What the bleep! is this kaka?!" The first

discs from the Tokyo CBS/Sony pressing plant were dreadful. Barbra Streisand,

bless her heart, was rendered hopelessly unlistenable with industrial-strength,

buzzing adenoids. The New York Philharmonic peeled wallpaper and neutered the

cat. Miles Davis' Quartet jazz instrumentals were rendered so stridently as to

cause widespread crop failures. And that was just the first three discs!

As far as I could tell, the over-hyped CD medium, though praised with celestial

adjectives by the media types, was seriously flawed and DOA. I not only

couldn't recommend it, I couldn't even listen to it.