You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 72

Notes of an Amateur: CPE Bach, R. Murray

Shafer, Lindberg, Goerne's Schubert.

Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, Magnificat; Heilig is Gott, WQ217; Sinfonia in D Sharp Major. RIAS Chamber Choir, Akadamie für Alte Musik Berlin. Hans-Christoph Rademann. Harmonia Mundi HMC 902167. Coming to the choral music of CPE Bach from that of his father, Johnann Sebastian, can be an thrilling shock, especially if the son is in the hands of Alte Musik Berlin who relish their difference. We leap from the baroque to the rococo, where textures are simpler, melodic lines are longer, and the atmosphere is more vibrant. Alte Musik Berlin's CPE Magnificat (1849) gives us religious faith that is bursting with more affirmative energy than reverence. I have always wondered how the world would hear this music if its composer were named anything but Bach. Or how the music would have gone down 40 years earlier with the conservative church officers of Leipzig with whom his father had to deal. The three works recorded here were the essence of a program presented on Palm Sunday, April 9, 1786—and it must have been a stunner. Just as in his keyboard concertos and solo keyboard sonatas, Carl Philipp Emanuel, while he's as respectful of his father as always, seems to be kicking over the traces of the older generation. We are clearly approaching the age of Mozart. I'm sure there are some who would play especially the fast sections of the Magnificat at a slower pace, reducing contrast with the slower ones—and with the music of the father. I'm sure Rademann and his musicians are conscious of a desire to do quite the opposite. Even the soloists—bass Markus Eiche in particular—sing with notable gusto. And when alto Lehmkuhl and tenor Odinius sing the duet in section six, we are a good deal closer to opera than Johann Sebastian's church would have put up with. It is possible ones response to this interpretation of the work will depend on how Lutheran one is! To return to one of my earlier remarks, were CPE named something other than Bach, based on this work I'm confident we would be ranking him alongside Haydn, whose several oratorios are to my ears a step behind Carl Philipp's in shear eloquence. But then I haven't heard Alte Musik Berlin play Haydn! Heilig ist Gott (1776), composed 27 years later, is even more moving than the Magnificat. Its mood is appropriately more somber, though this doesn't much daunt AMB who are so much in love with the composer's partaking of the spirit of a new musical age they're not about to hold much back. And based on the results, few are likely to fault them. Sinfonia in D# Major (1780), with no religious concerns to address, is pure CPE Bach exuberance and joie de vivre. A great album that will be a revelation to some of you.

R. Murray Schafer, String Quartets, Nos. 8-12. Molinari Quartet. Atma ACD2 2672. (2 cd's). Canadian Murray Schafer (b. 1932) is about as close to being a unique composer as one can be these days. His heart is romantic, his language tends toward dissonance—and thus his music is fiercely rhapsodic. It is the ferocity that keeps keeps everything in the air. That said, in the first two quartets programmed here, he also exhibits a need to step outside his form—in Quartet No. 9 (2005) with children's voices; in Quartet No. 10 (2005) with a paragraph of spoken commentary. Depending on how you feel about ‘mixed media,' this will either please or dismay you. His music certainly does not require these...intrusions...to move us and could be said to break the spell, bringing everything back to earth and limiting its power of ramification. I prefer artists, especially those with the eloquence and skill of a Murray Schafer, who have faith in the power of their art to suffice. I have yet to hear his earlier quartets, so I don't know how often he yields to this temptation. Quartet No. 11 (2006) is all music and to my ears the better for it. Unlike most music, it does not make us think of other music as it takes us into its own realm. I consider this a rare accomplishment. Quartet No. 12 (2012) flirts with impressionism but soon enough moves on to other musical matters. There is a tendency to swoon here and there and also peculiar, elusive recalls of popular stage music, idioms of the 1940's and 1950's. On the whole this quartet feels almost like a personal memoir. "The mood changes rapidly throughout the single movement of the work, alternately the lyrical and suave with the fast and energetic. One might find the tempo unusual for a composer approaching eighty years old." (RMS) Quartet No. 8 (2000-2001) completes the program. The first of its two movements is an adventurous olio of different styles, which apparently take their thematic coherence from references to the lives of its dedicatees. The second, in which a pre-recorded quartet plays alongside a live one, is a whole musical world unto itself—dark, reflective, emotionally intense—occasionally very moving. An unsettling (alarming?) shrieking motif appears in both movements. As a two-part work, Quartet No. 8 is difficult to digest: each half insists on its own, largely separate existence. I was alerted to the existence of Schafer and his quartets by composer and Fanfare Magazine reviewer Robert Carl, who admires him enormously. (Volume 37, No. 3, Jan/Feb, 2014). Carl and I agree on Schafer's overall aesthetic but I have more listening to do before my admiration catches up with his. I recommend his review to those whom I've made curious.

Magnus Lindberg, Violin Concerto. Jubilees. Souvenir. Pekka Kuusisto, violin and director for the concerto; Tapiola Sinfonietta, Magnus Lindberg, conductor for Souvenir and Jubilees. Ondine. ODE 1175. A leading light among Finnish modernists, which is saying a lot, Magnus Lindberg is the perfect complement (antidote?) to fellow Finn Kaija Saariaho, meeting her mystic spirituality with an intense and disciplined Scandinavian protestant severity. His Violin Concerto has some of the boldness of Thomas Adès,' though not quite its humanity. Ligeti's also belongs in a comparative discussion. The first movement is cool (arctic?) and resolute. We hear a six note theme drowning in a dissonant storm. It re-emerges in the second movement but the storm soon returns to sweep it away... until it returns again. The violin is then allowed to solo for a while, with and without the theme. The third and final moment adds intensity to the mix (as if it were needed!) and then concludes with a soupçon of harmonic relief. I am tempted to say this work feels more Swedish than Finnish and my wife's Finnish relatives would likely agree. Jubilees (2000-2002) a work for small orchestra, is more variable in mood and will strike some resistant to the charms of the concerto as more interesting; but there is sufficient bluster to it to remind us whose musical world we are in. And it concludes with a fierce, stalking movement that even a valedictory oboe can't deliver us from. Another work for small orchestra, Souvenir (2010), is the most recent work in the program. The mood here has warmed a bit. It is intended as an elegy for two of the composer's former teachers, so we spend somewhat more time in middle of the keyboard than in the other works. That said, Lindberg's essential qualities remain in force. His cool, stoicism is never far away. Overall, Lindberg's musical world has become uncompromisingly Type A. It asserts an unindulgent, sometimes threatening, emotional landscape over which it claims dominance. It tests our willingness to submit to and abide for a while in a world where the traditional rewards of music are given little room to breathe, which is after all what a great deal of modernism is about. Don't let me drive you away if you're bold of spirit. Lindberg has a large following in the musical world, so he's clearly got his hands on at least a part of our zeitgeist.

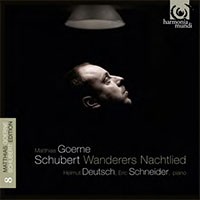

Schubert. Wanderers Nachtlied. Matthias Goerne, baritone. Helmut Deutsch, Eric Schneider, piano. ‘Goerne Schubert Cycle, Vol. 8.' Harmonia Mundi HMC 902109.10 (2 cd's) There are two things going on in every performance of Franz Schubert's lieder: there is Schubert and there is a voice, setting aside for the moment the pianist. I make this obvious remark because Peter Pears,' Dietrich Fischer-Diskau's, and Mathias Goerne's Schubert are very nearly three different composers. And there is no getting around this. Despite what I will say at the end of this review, there is no definitive Schubert lieder any more than there are definitive Schubert piano sonatas. And human voices differ more than pianists and their pianos. Schubert's lieder is his greatest music. It is also the most protean. It changes its very being depending on its interpretation. I am fond of its painfully lyric eloquence coming through the voice of high tenor Peter Pears; and of the smooth richness that comes through Fischer-Diskau. But from Mathis Goerne, I hear music that almost literally makes the earth move, as it surely must have done in the musical mind of the composer himself. Goerne sings like God's cello, the instrument most often compared with the human voice—the entire range of the cello. There is a timbre to his voice that no other Schubert singer can approach. And the piano accompanists Harmonia Mundi have blessed him with all (truly all of them) have the ability to make us believe we are hearing sonatas that have been given both deep roots and wings. Today it is Helmut Deutsch and Eric Schneider. We have 32 lied here, taken from many moments in his brief life. We have had some 250 or so to date. The Hyperion Records edition gave us somewhere around 350. How many lied did Schubert compose? "Over 600." How far will this series go? Latest word is that there will be eleven volumes, which will give us roughly the same number of CD's as the Hyperion set. But all by Goerne! Excelsior. Equipment used for this audition: Resolution Audio Cantata CD player; Crimson 710 preamplifier and 640 mono-block amplifier; Tocaro 40 loudspeakers; Blue Circle BC3000II GZpz preamplifier and BC200KQ stereo amplifier; Jean Marie Reynaud Orféo Supreme loudspeakers; Crimson cabling. Bob Neill is a former equipment reviewer for Enjoy the Music and Positive Feedback. Since 2004 he has been proprietor of Amherst Audio in western Massachusetts, which sells equipment from Audio Note (UK), Blue Circle (Canada), Crimson (UK), Resolution Audio (US), Jean Marie Reynaud (France), and Tocaro (Germany).

|