|

You are reading the older HTML site

Positive Feedback ISSUE 63

From Clark Johnsen's Diaries: The Decline of true Acoustic Reference in Audio Magazines, Illustrated

Until that odd last word, this title is a truism. Although equipment reviews have become generously laced with notes on how various CDs and LPs sound, those conveyances themselves may well be unmusical or even amusical. Indeed most of them are, because their creators cared naught about the real sounds of music. Why should they? In today's desktop and earbud economy good reproduced sound barely registers—not that it necessarily ever did. So how does one distinguish the good from the bad? My own method assays individual instruments: Choose one. The cello? Okay, to my ear an electrical 78 from, say, 1936 played over a wide-range system with proper attention paid to surface treatment and stylus, as well as to all due high-end equipment choices and tuning techniques, will, for the cello, outperform any tinkly LP or edgy CD. (Of course triode tubes, ribbon mics, inert media and other paraphernalia of the day did play a role.) How about the human voice? I'd have to suggest an "acoustic" disc of some sort, a recording made without electrical intervention. The volume may be low but the effect is thrilling. Whoever has been privileged to hear one, never forgets the uncanny, realistic vocal quality. Transferring those older discs to newer reproduction media rarely if ever, alas, conveys the full, true sound. Thus we have become deprived of historical knowledge. Not to say that LPs and CDs (and tapes and downloads) never do the trick occasionally, too.* However, equipment reviewers rarely treat the source + system as something that ought to sound like actual instruments and voices. It's neither the job description nor the intention, hence listeners and customers also fail to heed such an imperative. That decline may be blamed on magazines. In the beginning there were no "audio" periodicals, even though there were gramophones and phonographs and Victrolas. The topic was covered spottily in music publications such as Etude (1883-1957), Phonograph Monthly Review (1926-1932), Disques (1930-33), American Music Lover/American Record Guide (1935-present), Record Review (UK) and Gramophone (1923-present) in the English-speaking world. (And what coverage! An article about this is planned for the near future in PFO. Also, writers back then were more concerned with "tone", a word one almost never hears these days except perhaps from Art Dudley. "Tone" addresses the similarity of reproduced sound to actual instruments, again not a present-day desideratum.) More recent music magazines with some audio reporting include Fanfare, Opus (now defunct) and Classic Record Collector, although these columns proved highly unreliable except for Neil Levenson's in Fanfare, a beacon bright unto a largely oblivious readership. As the technology of sound reproduction evolved in the Thirties and Forties, one could read about it in places like the Bell System Technical Journal, but no dedicated publication to my knowledge spoke to the semi-professional and lay readership until 1947, when Audio Engineering magazine first appeared – a successor of sorts to Radio. In 1951 High Fidelity was launched in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, by music critic R.D. Darrell, former managing editor of Phonograph Monthly Review, and friends. Seven years later it was joined on the newsstands by HiFi and Music Review, shortly to become HiFi/Stereo Review, then simply Stereo Review. In England Hi-Fi News began in 1956, soon thereafter to combine with the longer-established Record Review to become HFN/RR, which bills itself as "the longest serving and most prestigious hi-fi and music magazine in the world." But the idea of an audio specialty largely separate from music had already affixed itself to the hobbyist and consumer mind. Then along came J. Gordon Holt to create a niche within a niche, later called high-end audio. Credit for that term goes to, or is assumed by, Harry Pearson; together the two men forged an uneasy kinship and gave us a pursuit that's enjoyed today both for reading and as a hobby. Holt's revolutionary column in High Fidelity had been called "Tested in the Home" (TITH), which birthed the concept of non-bench, non-meter testing—soli auri. Pearson coined the phrase "the absolute sound"—unmistakably relating to instruments, the old-fashioned way—and named his magazine that. Holt already had gone an alternate route to found Stereophile. (An aside: A couple decades ago I sketched a parody issue to be called The Absolute Stereophile. Audiophiles are so absolute in their views, you know! One goof was to have the reviews be a single sentence each, with everything else contained in multiple footnotes, expanding upon the then-HP-style.) (Another aside: My great old friend and audio buddy Tony Lauck introduced me to Stereophile, as he earlier had Paul Krassner's The Realist, "often regarded as a milestone in the American underground or countercultural press of the mid-20th century." Nice pair, Tony!) While The Absolute Sound paid some respect to, for lack of a better word, tone, Stereophile continued the noble TITH tradition of measurements-by-ear. Somewhere in the mix too were upstarts Sounds Like…, Fi, Ultimate Audio and especially Listener, all now gone. Meanwhile the mass-market-oriented magazines had not totally abandoned the sounds of acoustic instruments as front page material… yet. You'll see. And now, ladies and gentlemen, let the show begin. A tale told by art directors, editors, and publishers. First, just because they're so beautiful, some covers from Etude to set the stage:

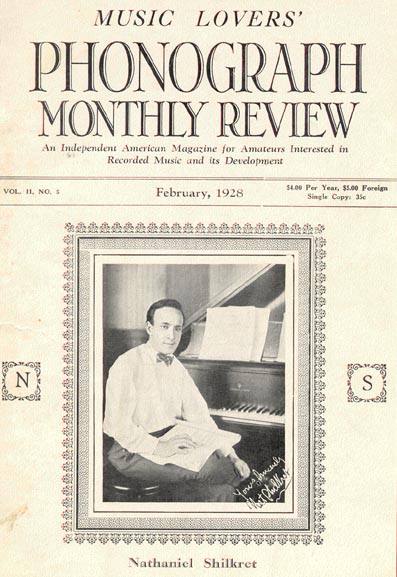

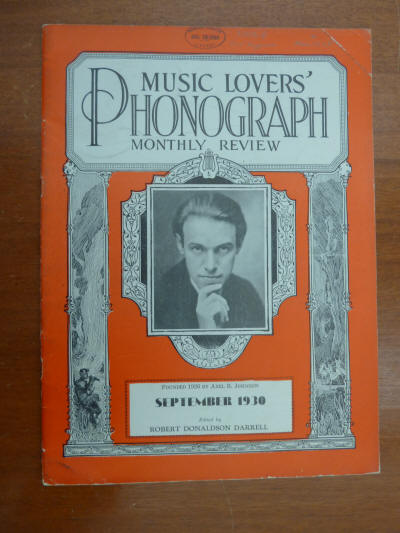

And a couple from Phonograph Monthly Review:

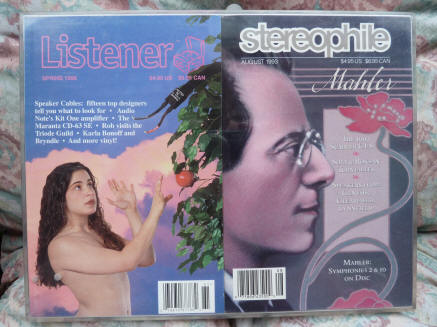

Now presenting, for their porno shock**:

But not that long ago, covers looked way more musical:

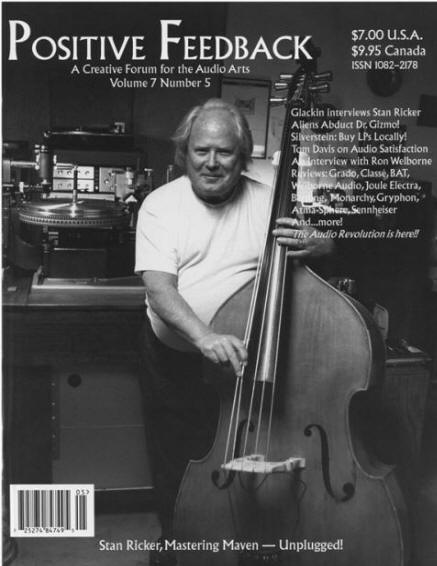

Positive Feedback too, back in the good old (better?) days of print, weighed in with a classic B&W cover featuring a shot taken by Dave Glackin, of Stan Ricker plucking his bass fiddle. (Dave told me that Stan had remarked, because the string makes such a notable compression wave, "This one's for Clark.")

Although back in the early Sixties, here was the value presentation:

And there I rest my case, illustrated. *Trouble is, when the ensemble expands to include more than maybe two players, the older recordings begin to lose their lustre. With electrical 78s the string quartet still sounds pretty good and several individual voices not too shoddy, but for an orchestra or a chorus one must indulge in some suspension of disbelief. Still, there is considerable sonic quality to be enjoyed. ** From my report on High End 2002 in New York: Throughout my rambles I've carried a peculiar display I've mounted consisting of the two covers of the two major high-end magazine's current issues placed side-by-side. Quite the little item! Not only are they the exact same color scheme, but both covers feature tall slim grey loudspeakers pictured dramatically slantwise, but mirror-imaged! That's the only real difference between them. It has come to this: How can art direction generate the most newsstand sales? Gone, the days of whimsical or musical covers. Gone, forever.., until a new breed of magazine commands attention, which it inevitably will, just as Stereophile and TAS once did. (Listener continues the old tradition, but how much longer?)

At any rate, my crafts

project elicits some cool comments. Allen Perkins:

"A stereo pair!" Oakroot:

"Eye candy for the ear." Joe Skubinsky: "A new

format war?"

|