|

You are reading the older HTML site Positive Feedback ISSUE 44july/august 2009

The Lion and the Wolff

Expand Territory to SACD

Re-mastered right and painstakingly transferred to digital, Analogue Productions delivers a bevy of Blue Note titles

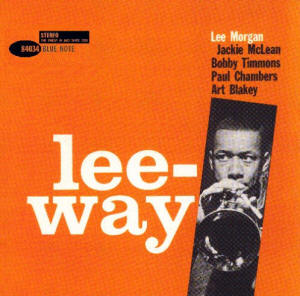

Cue up track two of the

recently released SACD, Lee Morgan, Leeway. A

vamp played in unison by Paul Chambers on bass and

Bobby Timmons on piano gives way to a diabolically

groovy melody harmonized by Morgan's trumpet and

Jackie McLean's alto sax that melds into a

complicated blues riff. Featuring shifting scales

and time signatures pulled off with effortless

abandon by the multi-rhythmic Art Blakey on drums,

The Lion and the Wolff is Morgan's ode to Alfred

Lion and Francis Wolff of Blue Note records. As the

musicians cut into the meat of the track, one

quickly realizes that the tune epitomizes Blue

Note's legacy, beyond Morgan's sharp staccato

blasts, On the Lion To digress for a moment, Blue Note has long been my favorite record label. After developing a thirst for John Coltrane's quartet of the early-to-mid 1960s and Miles Davis' quintet around the same period on the Impulse and Columbia labels, I went searching for similar material not under the principals' names. The search quickly found me staring at a curious album cover. Its monochromatic photo showed the face of a striking Japanese lady in somewhat soft focus in the right hand foreground and Wayne Shorter, wearing a dark suit, tie, starched white shirt and serious expression, partly obscured by vegetation behind her, on the left. At the top of the LP cover, centered in small type were the words "Speak No Evil". Just above those words a fleshy, red pair of lips was planted, as if a woman wearing lipstick had kissed the album cover and left her mark. To the right of this insignia was the Blue Note logo, a stylized ovular note with tiny lettering, "The finest jazz since 1939." The musicians on the album were a distillation of the Miles Davis quintet, but with Freddie Hubbard on trumpet and propulsive Coltrane drummer Elvin Jones replacing Tony Williams. As a jazz novice, discovering my first Blue Note album was like finding a gold mine by accident. The choices of musicians, compositions and soloing offered an endless reserve of fiery, bluesy, thoughtful, elaborate and nuanced jazz—beyond other labels. I would later discover that this was at least partially attributable to Blue Note's policy of paying the musicians not just for the recording session but for a practice session where the details of the compositions and measures allotted to each soloist could be worked out in advance, while still allowing ample room for improvisation. Even the packaging exuded class. Francis Wolff's photos and Reid Miles' designs captured the musicians' mood, charm and conception, encapsulating it in a special time and style. Above all, it was producer Alfred Lion's innate ability to identify, assist and assemble the greatest combinations of talent in the jazz world that made Blue Note stand out. It wasn't just Speak No Evil. Many of Blue Note's albums from the mid-sixties feature performances of immense beauty and timelessness by the sidemen of Trane and Miles—sessions that would never have been recorded if not for Lion's keen awareness that the musicians in those bands could have and should have been (and later became) bandleaders in their own right.

Of course Blue Note's

impact started long before the mid-sixties. It is

impossible to fully enjoy the discographies of jazz

legends like Bud Powell, Art Blakey, Thelonius Monk,

Horace Silver or Miles Davis without their classic

Blue Note titles. Jimmy Smith recorded more than 40

sessions as a leader for the label between 1956 and

1963. On the other end of the spectrum, some of the

catalog's gems were headlined by artists who were

relative no-names or rarely given the reins to lead

a recording session. Unknowns like Tyrone Washington

whose Natural Essence album is, in

retrospect, a standout from 1968 featuring then new

trumpet sensation Woody Shaw. Or Pete La Roca's

masterpiece as a leader,

The debt owed to Blue Note

and Alfred Lion is all the more interesting because

of the producer's heritage. One would expect an

American to dedicate his life to the uniquely

American classical music form of jazz in the way

that producing records requires. But Lion was born

in Analogue Productions to the Rescue

After Blue Note was sold

to But those days are ending. As the audiophile community is now well aware, Chad Kassem's Analogue Productions label is releasing 50 Blue Note titles both in 45 rpm heavy vinyl and subsequent SACD versions. Each title is expertly re-mastered by Steve Hoffman and Kevin Gray--the best re-master engineers in the biz. The 45s made available so far have been widely praised in many online and print forums as the best sounding versions ever released. For the first time, audiophiles do not have to sacrifice their high standards when collecting Blue Note titles—at least for this limited run of 50. Hopefully it will be extended to a second batch and then a third and fourth until a significant percentage of the catalog has been reissued by Analogue Productions. But what of the SACD versions that are dribbling out slowly and a bit behind schedule? How do they stack up? Several years ago, Blue Note/EMI did issue a small batch of SACDs. The only classic title in the bunch was Blue Train, one of the flagships in Blue Note's prodigious catalog. Unfortunately, its sound was a let-down, lacking in extension, air and realism, barely surpassing CD versions. When Blue Note announced no more SACDs would be forthcoming, I was only partially disappointed. If the lackluster audio of Blue Train was the best that the label could muster for one of its most legendary titles on a superior digital format, what was the point? Not long after that, most labels aside from classical boutiques stopped issuing SACDs. That seemingly doomed my dream of seeing vast swaths of my favorite jazz impeccably produced on the format. So to understate the matter, it was a very welcome announcement when Analogue Productions hired Gray and Hoffman, who undertook the challenge of re-mastering Kassem's choice of the 50 Blue Note titles for 45 rpm vinyl and SACD. At $50 a pop, the vinyl is too rich for my blood—though it is worth every penny—but the $30 cost of admission for SACDs was not too high to start collecting my favorite titles in the batch. So far I have had the pleasure of hearing the SACD versions of: Art Blakey, Moanin' John Coltrane, Blue Train Kenny Dorham, Whistle Stop Dexter Gordon, Dexter Calling Jackie McLean, Capuchin Swing

Lee Morgan,

Leeway

Art There is not a dud in the bunch. Relative to Blue Train's earlier incarnation on SACD, the piano on has the overtones that communicate the keystroke and soft mallet against the strings, with the wood resonances. Rudy Van Gelder close-mic'ed all the instruments and everyone always knew there was ample detail to mine in these recordings. Finally, re-master engineers are involved who know how to extract every drop of detail, and boy does it pay off. Listen to Philly Joe Jones' shimmering hi hat and ride cymbal groove of the latin tinged title track of Whistle Stop. Each drumstick strike carries a weight and airy treble detail not heard on previous digital versions, which tended to deaden the piano and treble attack as well as add a muffled and boomy quality to the bass. The new SACDs are significantly improved. Bass is taut and supple. Horns sound lively and bright, with a heftier bite to them as opposed to the thin, tinny sound of the CD. All these aural cues translate into greater presence and realism. While there is some variability from title to title, Van Gelder had his technique pretty well dialed in for these recordings and the re-mastering efforts by Gray and Hoffman are uniformly excellent. To Mono or Not to Mono Analogue Productions had a quandary on its hands when the time came to produce its first batch of Blue Note re-masters. Many record collectors associate monaural pressings with superior audio performance. In the words of Acoustic Sounds, "Mono Blue Notes are typically much more desirable on the collector's market. Because of that, the assumption of everyone involved with the Blue Note reissue project was that the mono master tapes were going to sound better than the stereo master tapes. Imagine the surprise when mastering engineers Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman discovered that there were no true mono master tapes for sessions later than October 1958! But of course the real proof is in the reel. Without a single exception, Kevin, Steve and everyone involved agreed that the stereo masters sounded vastly superior to the summed mono masters. The stereos, in every instance, sounded much more lifelike with far greater detail, air and ambience." Another reason the Analogue Productions chose to issue the titles in stereo was to give listeners a choice in system playback. You can still hear these reissues in mono if you have a mono button on your preamp or by using a Y-adaptor to feed the two stereo channels into mono. Actually, using a Y-connector is exactly what recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder did to produce the monaural masters for LPs that have become collectors' items. But those are all sourced from the original stereo masters from late 1958 onward. According to Acoustic Sounds, "every Rudy Van Gelder Blue Note session after October 30, 1958 was recorded in stereo only. The mono releases of those recordings were created by folding down the stereo master tape. In other words, there was no true mono master, only a stereo master that then birthed the mono master. There was a short period of time--March 1957 to October 30, 1958--when Van Gelder did in fact run dual mono and stereo session tapes. For Blue Note from that period of time, the mono version was in fact cut from a mono master. In fact, the master tape boxes from these great sessions each include a notation by Van Gelder himself that says, ‘monaural masters made 50/50 from stereo master.'" Whether you've collected stereo or mono Blue Note titles before or you're new to the label or the genre, if you're looking for the ultimate in digital audio presentations from the golden age of jazz, look no further than Analogue Productions' SACDs. The initial batch of 50 might not be the titles I'd choose if I had my druthers. But as the teenagers these days say, "it's all good". Indeed some of Blue Note's most critically acclaimed and famous titles are presented in this batch, including Cannonball Adderly Somethin' Else and Kenny Burrel's Midnight Blue. One can only hope that the sales from the initial 50 are significant enough to warrant further batches from Analogue Productions. Chad Kassem did his part. Kevin Gray and Steve Hoffman did their part. I'm doing my part. Now let's all pony up and let the sweet sounds of Blue Note wash over us and take advantage of this tremendous opportunity to hear the music we love re-mastered the way it deserves to be.

|